FEMA has invited developers, alert originators and broadcasters to use its IPAWS Laboratory for testing purposes. The lab is at the Joint Interoperability Test Command in Indian Head, Md. FEMA officials say the IPAWS-OPEN system running there is not connected to carriers or broadcasters and is a safe environment to conduct tests.

Credit: Photos by Leslie Stimson

WASHINGTON — The adoption of Common Alerting Protocol standards for EAS is facing challenges but it is not stalled, according to industry participants. However, some of those experts also say technology is moving far faster than the overall EAS ecosystem can react.

FEMA officials continue their push to get more local emergency managers authorized to send CAP messages as part of the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System, or IPAWS, by promoting education, training and coordination among EAS stakeholders. But the EAS community is still shaking off public ridicule after the “zombie” hacking incidents in February.

Bogus alerts aired on television stations in three states and at least one FM radio station in Los Angeles, according to several sources. The attack immediately prompted security concerns from some warning professionals worried that the Internet component sacrifices EAS security for the sake of technology.

EAS observers believe an individual or group hacked the TV stations’ EAS encoders/decoders by taking advantage of those with weak Internet firewalls and factory default passwords. The fake alerts, which warned of zombies “rising from their graves and attacking the living,” made it to air in at least three cases.

FCC officials cautioned broadcasters to change default passwords for their EAS decoders and ensure that their IP networks are firewall-protected, also with strong passwords. The commission and the FBI continue to investigate the hacking, according to a variety of sources.

Warning experts theorize that those responsible were familiar with the technical infrastructure of broadcast EAS and how it works. A spokesman for Northern Michigan University in Marquette, Mich., licensee of WNMU(TV), told several media outlets that the attacks on the school’s station was traced to an overseas source by the school’s forensics information technology staff.

More broadly, the “buzz” in public alerting right now focuses on social media and smartphones, which quickly are gaining acceptance as public warning expands across multiple delivery platforms, according to one EAS expert.

A local emergency manager told Radio World that in an emergency, “I’d contact local media, send a message through Facebook and Twitter and use our own local emergency notification system long before I start working on the EAS alert.”

Smartphones — and their connectivity to Twitter and Facebook — are gaining favor with some longtime EAS advocates. In some cases, emergency managers and public alerting professionals are embracing local emergency notification systems that use landlines and cellphones as a preferred means to local alerting. Some of these systems are not tied into EAS in any way.

‘More is better’

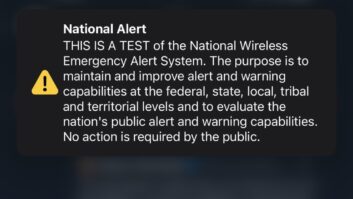

U.S. wireless carriers continue to roll out the Wireless Emergency Alerts service, formerly called the Commercial Mobile Alert System. It complements the Emergency Alert System, according to FEMA.

WEA allows public safety authorities to use FEMA’s IPAWS Open Platform for Emergency Networks to send geographically targeted, text-like emergency alerts to the public. They relay presidential, Amber and “imminent threat” alerts to mobile phones, according to FEMA, which expects the majority of the alerts will come from NOAA’s National Weather Service.

The WEA text service is limited to 90 characters, which some observers feel could compromise WEA’s potential for public alerting, given that a phrase like “tune to local media” might occupy part of each message.

Nevertheless, some in the EAS community are accepting of the technology.

“There are several reasons why many of us in the EAS business have a favorable view of wireless text alerts on cellphones,” said Adrienne Abbott, Nevada EAS chair. “It’s a case of ‘more is better.’ When there’s an EAS activation, the wireless text alert adds to the credibility of the EAS message.”

Abbott said that in an emergency, more information is always desirable. It can only help if people hear a warning on their radio or TV and then get a text message with the same warning on their cellphone and even from a telephone notification system such as Reverse 911.

“Radio and TV do a good job of getting warning messages to the public, but a wireless text alert can reach people, like those in many workplaces, who aren’t listening to a radio or watching TV, or who have cut the cord and no longer have a traditional landline telephone,” Abbott said.

FEMA IPAWS EAS Test Program Manager Manny Centeno, speaking during a webinar in March, said “broadcast remains the backbone” for EAS, although the government agency supports WEA.

FEMA continues to push for local emergency managers and alert initiators to sign up for IPAWS, Centeno said, adding that the organization stresses best practices to emergency managers.

“We don’t have a lot of them using it just yet,” he said during the webinar. “We are projecting some education to guide them to bridge the gap between broadcasters, cable operators and the local emergency managers. You have to remember that [IPAWS] is brand-new and people are unfamiliar with it.”

But Centeno acknowledged some reluctance by emergency managers to use CAP EAS when they are not trained properly. “You can’t wait to figure this out when you are experiencing an emergency. The disseminators have to construct solid messages.”

Leadership, funding

The CAP EAS Working Group of the FCC’s Communications Security, Reliability and Interoperability Council made its final report to the commission in March. The group identified a need for best practices to guide emergency managers and the system development community in the process of CAP EAS message origination.

Sgt. Robert Ott, emergency manager of Ingham County in Michigan, says leadership and funding for training for IPAWS and CAP EAS has been lacking.

“FCC and FEMA are going to have to push CAP EAS out more aggressively. We are one of only a half-dozen counties that has been approved as IPAWS users in the state of Michigan. That isn’t many,” Ott said.

“I don’t really get all the technical stuff. They seem to have an acronym for everything. What we need [at the local level] is simplification.”

Ingham County uses the Code Red community notification system, a product of Emergency Communications Network. It uses Reverse 911 and cellphone alerts to communicate local emergencies. Reverse 911 uses a database of telephone numbers and addresses to deliver a recorded emergency notification.

Meanwhile, the CAP rollout is “not going well” in Illinois, said Wayne Miller, chairman of the Illinois SECC.

“The state has not shown much interest in working with FEMA to develop a CAP server system in Illinois. Without a central server, local managers have nothing to embrace,” Miller said. “And since there is nothing new operationally, the state EAS plan has not been revised or updated.”

FEMA and FCC officials declined to comment for this story.

The FCC is encouraging State Emergency Communications Committees to review their state plans to ensure they are up to date, particularly regarding monitoring assignments and handling of CAP/IPAWS, and to make amendments if necessary, according to earlier comments from commission officials.

Jim Skinner, Nebraska SECC chair, said some local emergency managers in that state are “very on board with implementing CAP messages to IPAWS” even though only one county in that state has been authorized to use it.

“There are clear challenges for CAP on IPAWS. The size of all the National Weather Service data is too overwhelming to use IPAWS for weather EAS right now. Fortunately the WEA filtering seems to reduce it to a manageable amount of data for cellphone alert. We have had a few WEA weather alerts in Nebraska that worked well,” Skinner said.

Satellite delivery

Meanwhile, Centeno confirmed during the FEMA webinar that the government agency’s buildout of Primary Entry Point stations will conclude soon. The majority of the PEP stations now have satellite systems to downlink alerts from FEMA, he said.

“The final phase of deployment and testing is underway. It should be operational by the middle of this year,” Centeno said.

FEMA’s satellite delivery network will send audio from FEMA to the approximately 74 PEP stations nationwide. Satellite delivery is expected to improve audio quality of messages, Centeno said during the webinar.

Poor audio quality was a major concern after the first national test of the EAS system in November 2011. This was emphasized further in a report about the national EAS test issued in April by the FCC’s Public Safety & Homeland Security Bureau.

The report found that some areas had no Primary Entry Point station to provide a direct connection to FEMA, while other stations could receive but not re-transmit the test.

The feds also noted that some EAS gear couldn’t handle the short test, which was truncated from some two minutes to just 30 seconds before the November 2011 event.

FCC Public Safety & Homeland Security Bureau Chief David Turetsky told lawmakers recently the satellite feed from FEMA to PEP stations will be used to back up the Public Switched Telephone Network-based connection.

“The openness of the Internet also makes it more vulnerable to certain types of exploits, and specific areas of risk exist in Internet routing,” Turetsky noted in testimony before a House subcommittee hearing on alerting in March.

In the report, the Public Safety & Homeland Security Bureau emphasized that there will be another national EAS test, but first it recommendsa rulemaking to review equipment performance during EAN activation; seeking public input on proposed changes, if any, to EAS equipment rules; and encouraging states to review and update their EAS plans, especially regarding monitoring assignments. FCC officials have said the test revealed that many stations didn’t know which facilities in their markets to monitor to receive the alert.

EAS equipment manufacturers are watching industry developments, including the zombie hack incident, and seem optimistic that broadcaster investment in CAP equipment will not be lost. Broadcasters were required to have Common Alerting Protocol-compliant EAS equipment in place in June 2012.

“Reports indicate the CAP weekly tests from FEMA have become reliable,” said Sage Alerting Systems President Harold Price. The CAP/EAS community, he said, “is working out all the kinks” in getting units to poll the Internet for alerts properly.

The next big challenge on the horizon is when the National Weather Service begins sending weather alerts through the public IPAWS server and out to stations, according to Price.

“Once their final format is in the place, CAP EAS vendors may need to put some text-to-speech tuning in place to better handle the NWS text format. I don’t think we’ll see NWS alerts on CAP for a few more months,” Price said.

TFT Senior Vice President Darryl Parker said live streaming of event codes present some issues.

“FEMA, moving away from a telephone conference bridge arrangement to deliver ‘live’ audio to PEP stations, is now in the process of a satellite delivery system to connect PEP stations. For the legacy EAS, ‘live’ audio from PEP stations propagated through the web structure of EAS RF monitoring assignments presents no problem,” Parker said. “However, for ‘live’ audio to be streamed as part of a CAP-delivered EAS message, there are several problems.”

The CSRIC CAP EAS Working Group report mentioned a need for further development of a CAP EAN streaming audio capability.

The concern is the Internet bandwidth required by a server, or network of servers, to connect thousands of EAS participants simultaneously, Parker said.

“This can certainly be done, but funding is a paramount obstacle,” he said.