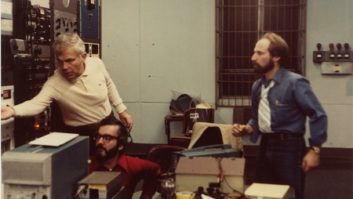

As part of a continuing series, Radio magazine is interviewing authors included in the recently published 11th edition of the NAB Engineering handbook.� Bob Orban is a well-known designer of audio processing devices.� His chapter in the handbook is 7.2 entitled �Transmission Audio Processing.�

�

Radio magazine:� Bob, though broadcasting had been going on for nearly 60 years by the late 1970s, the field of audio processing was in its infancy. The Orban 8000 was revolutionary when introduced. Why was there so little emphasis on audio processing up to that point?�

Robert Orban: In fact, there was quite a bit of awareness of audio processing, mainly thanks to CBS Laboratories� heavy marketing and promotion of the Audimax/Volumax starting around 1962. At least in the New York City market, the loudness wars were well underway by the time that the 8000 was released in 1975. Eric Small, who was the marketing agent for the 8000, had a booming consulting business in the New York market. This included comparative loudness measurements using the first-generation CBS Loudness Meter, and resulted in an early 8000 marketing tagline: �The 3dB Edge.� Additionally, by the early �70s Mike Dorrough�s DAP-310 three-band Discriminate Audio Processor was making its way into many sophisticated stations� audio chains and made broadcast engineers aware of multiband processing for the first time. There were also a number of proprietary, customized chains in stations, such as the late Bob Kanner�s rack full of processing for what were then RKO stations like San Francisco�s top-40 KFRC (AM).

Radio:� If memory serves, you followed up the 8000 with the 9000, for AM. Aside from some proprietary lashups for AM stations, what was your new product going up against?�

Orban: There were three main competitors for the 9000. The first was the Dorrough DAP-310, which had been on the market for five years before the introduction of the 9000, and which had achieved considerable popularity. The second was the ubiquitous Audimax/Volumax combination, which was by then in its third generation. The third was the highly competitive Circuit Research Labs boxes that had been launched about a year earlier by Ron Jones and Gary Clarkson.�

The 9000 was designed to go head-to-head with the best custom processing chains on the air at the time. It introduced some ahead-of-its-time concepts, including a distortion-cancelled clipper whose drive level was determined by a psychoacoustic model of clipping distortion, a soft-switching polarity follower that used a tunable first-order allpass filter to flip polarity without clicks or pops, and a steep-slope receiver equalizer that was rendered usable by an overshoot-controlled 11 kHz lowpass filter to prevent sideband splatter. Not every transmitter at the time could take the 9000-processing audio without overload (or even damage), but those that could definitely stood out on the dial.�

Radio:�There was a time when radio engineers spent countless hours doing everything they could to maximize the quality of their program audio. Do you think radio engineers pay more or less attention to the quality of their program audio now than they did say 20 years ago? �

Orban: I would have to say less, mainly because engineers are spread so thin these days, but also because digital audio chains are not subject to many of the degradations, particularly noise and distortion, that could occur with analog facilities in need of maintenance. Digital chains have their own problems: when they crash and burn they usually create serious artifacts (including mutes that can put a station off the air), but these are so objectionable that they are more likely to be addressed immediately compared to an analog chain that (for example) acquired a faint crackle due to dirty contacts somewhere in the path.�

Radio: Imagine for a moment that you are updating your chapter for the 12th edition of the handbook, ten years hence. What do you think might be edited, or at least de-emphasized, looking to the future?�

Orban: I expect that analog transmission technologies, particularly AM, HF and analog STLs, will be deemphasized in future editions. The 11th edition already increased emphasis on digital transmission technologies. Additionally, certain groups such as PLOUD in Europe have been pushing to eliminate transmission audio processing altogether in digitally-delivered media, instead statically normalizing each program element to a given target loudness and leaving dynamic range compression as a function in the receiver. This requires active participation from the listener/viewer and has always struck me as utopian.�

The broadcasting landscape is changing quickly as Internet streaming gains more and more traction, and if the 12th Edition is issued a decade from now, processing over-the-air broadcasting may be significantly deemphasized. However, I expect FM radio will still be important in a decade (although its audience will continue to age), and I am also confident that the art of audio processing, which can transform a �jukebox� into an integrated, coherent presentation with a signature sound and show-business sizzle, will survive regardless of the transmission medium between the creator and the consumer.� �

�