Although most of the history books completely ignore what transpired at Brant Rock, Mass., on Dec. 21, 1906, those of us with an interest in radio should mark it prominently on our calendars — one to celebrate, perhaps by hoisting a tankard of lager (Canadian) in memory of the individual who set the stage for radio broadcasting on that date 110 years ago.

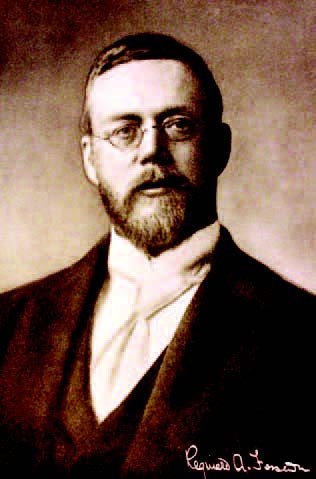

I speak of one Reginald Aubrey Fessenden, a Quebec-born, largely self-educated scientist, who had endeavored to give radio a voice for many years and was finally ready to pull the wraps off of his invention and show it to the world that Friday afternoon.

Wait, you may say; Aren’t you mistaken, wasn’t that Dec. 24, 1906, Christmas Eve?

Well, yes and no. True, most of the history books (and now websites) credit Fessenden with transmitting a short Christmas Eve program of recorded and live music, along with a scripture reading and a yuletide greeting.

However, validation of this event (the one solitary account was provided by Fessenden himself more than 25 years after the fact) has never been satisfactorily accomplished, despite attempts first begun more than 80 years ago and involving a number of individuals.

Despite numerous searches, there is absolutely no contemporary evidence that the celebrated Christmas Eve transmission ever took place. Yes, there is plenty of “hearsay” evidence — second- and third-hand accountings and remembrances — but such anecdotal tidbits don’t really count in the eyes of the historian. If he or she wishes to substantiate an historical occurrence, a “primary source” (a document, diary, logbook, manuscript, etc.) that was created at the time under study is essential. Sadly, no such primary sources have been unearthed to give credence to Fessenden’s solitary claim, which he penned in a letter dated Jan. 29, 1932 — a very considerable temporal distance from Dec. 24, 1906.

On the other hand, there is a comparative wealth of “primary source” information to substantiate Fessenden’s claim made in the same letter to having wirelessly transmitted speech and music sometime after 2 p.m. on Dec. 21, 1906.

I’d like to share some of this with you, as well as provide a bit of insight into what led up to that event, courtesy of Fessenden’s son, Reginald Kennelly Fessenden, who donated a large amount of his late father’s papers, pictures and other items to the State Archives of North Carolina shortly before his own death in 1944.

This up-close documentation allows us to zoom in on Fessenden, the company that he operated, the National Electrical Signaling Company, and the Pittsburgh businessmen who bankrolled this operation, Hay Walker, Jr. and Thomas H. Given.

A RELATIONSHIP GOING SOUR

By 1906, and after years of sinking very large amounts of money into Fessenden’s research in developing a practical wireless communication system, relations between Fessenden and his backers had become somewhat contentious, with Walker frequently admonishing the scientist about wasting time and money.

There are several such communications, but this excerpt from an April 27, 1906, memo seems to set the stage for what follows:

You speak of losing a couple of weeks trying to receive messages and of it being of no importance anyhow. Now that is the way it may look to you with your knowledge of science and may be all right, but when you come to illustrate in what you call a business way you are very, very far from happy and you are as far away from the question as I can possibly be in wireless.

To really get over [the top] is our aim and to be the first on record that is witnessed by people who are in every way disinterested would, as you know, be worth everything to us…the man or Company first over publicly have [sic] a great start in a business way, and that part now is of importance to us.

“Art is long but time is fleeting.”

Hay Walker, Jr.

“long gap” to ground was inserted above the base insulator when transmitting, and replaced with a “short gap” when receiving. At all other times the mast was kept grounded to provide lightning/static build up protection.) (Photo Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina)

As spring turned into summer, Walker (who spoke for both himself and his partner Given) became increasingly impatient with Fessenden’s dallying, pressing him to produce, wanting to see some sort of return on the NESCO investment, which after Fessenden’s firing in 1911 and the company’s being taken into receivership, would amount to more than $40 million in today’s money.

Walker, too, was aware of Fessenden’s tendency to multitask and overextend himself. Fessenden had convinced his Pittsburgh backers to establish not only a research laboratory at Brant Rock, but also a wireless equipment manufacturing operation in Washington, D.C., several U.S. experimental wireless stations equipped to handle telegraphic traffic, and two very large spark technology transmitting/receiving facilities — one located in conjunction with the Brant Rock lab and the other in Machrihanish, Scotland. (These coastal wireless stations were created to see if reliable transatlantic communication could be established — something that even Marconi had yet to do in the early 1900s — and if successful, generate revenue by undercutting message rates of the established submarine telegraph cable operation between North America and Europe.)

Fessenden didn’t believe in delegating authority, preferring to try to juggle the day-to-day operation of this sizable empire by himself — with some input, of course, from the men writing the checks in Pittsburgh.

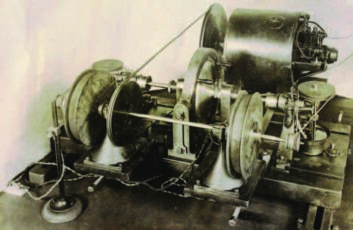

Corporate records show that Fessenden, in the latter half of 1906, was following multiple tracks: trying to boost reliability of communications between Brant Rock and Machrihanish, producing satisfactory “compressed air condensers” (capacitors) needed for high-power wireless operations, experimenting with short-distance radiotelephone communications across water, organizing a public demonstration of radiotelephony, and attempting to perfect the high-frequency alternator needed to power these latter two projects. Judging from surviving reports and correspondence, all seem to fairly equally occupy his time. (There were other smaller endeavors, too.)

Associated with all of these was the expenditure of a large amount of Fessenden’s time in writing reports and responding to queries from Walker, who was becoming increasingly concerned about Fessenden’s funding use. This Sept. 4 letter is indicative of how bad things had become and the growing state of dissatisfaction:

Dear Sir:

We acknowledge receipt of your letter of the 31st ult. and say in considering the state of our Treasury, it is an extravagant and uncalled for expense account, and we decidedly disapprove of it.

In our own accounts, anything beyond the bare necessities of getting from one place to another, comes out of our own pockets.

It ought not to be necessary to say this, but it is.

Yours very truly,

Hay Walker, Jr.

By this time (September) Walker had also become critical of Fessenden’s tendency to stretch the truth about what he had been able to achieve, as evidenced by this Sept. 24 telegram:

“Wire us what you have actually accomplished on [radio] telephone. No prediction.”

Hay Walker, Jr.

Interestingly, by the end of September, the aforementioned over-water radiotelephone demonstration, which had been a very hot item for several months and involved a lot of Fessenden’s time in trying to secure a small boat at a cost acceptable to Walker, seems to have dropped off the landscape completely.

With the beginning of October, activities focused more or less exclusively on creating a receive site some nine miles from Brant Rock, in Plymouth, Mass., in connection with the planned public radiotelephony demonstration, and in trying to boost communications reliability with Machrihanish. Records show that the latter project had become especially contentious, as the worsening of fiscal matters had led to some severe cutbacks at the Scottish station and a very bad morale situation among its operators.

“Office Instructions” from Fessenden to the Machrihanish manager drive this home, even revealing that Fessenden has considered trying to secure backing from other sources to continue his experimentation:

Oct. 9, 1906: “Give formal notice all [Machrihanish] employees of the termination of all contracts in conformity with instructions of Given & Walker on account of [Brant Rock/Machrihanish] messages cannot be exchanged.”

Oct. 10, 1906: “Given & Walker directed me to give all employees a month’s notice and I have mailed copies accordingly.

I do not think that this will amount to anything much but we may have to let go some of the men temporarily.

I want to avoid doing this if we possibly can because if we shut down even for a month it will make a great deal of trouble starting up again if the operators leave Machrihanish. Moreover it unsettles everything.

We can probably form a company soon and Mr. Westinghouse and some other men whom I have seen will come into it.”

Ultimately, Fessenden was able to convince his original backers to continue funding the Machrihanish operation, at least until he had done everything he could to boost the reliability of communications between Machrihanish and its Brant Rock counterpart.

However, in reports to Walker dated Nov. 12 and 20, Fessenden wrote that due to the effort being expended on the Plymouth site, along with a general shortage of manpower, he hadn’t been able to accomplish much in connection with transatlantic work. He closes by noting:

“We are installing the apparatus [at the Plymouth receive site] but will have to drop either the Trans-Atlantic or the [radio] telephone until we get another operator.”

Hay advised Fessenden to hire someone and to continue planning for both projects.

Pressure continues to build until the first week of December when word is received of a catastrophic accident at Machrihanish. Faulty guy lines and high winds teamed to topple the 420-foot tower (née smokestack), essentially putting the station out of business.

Efforts became focused exclusively on setting a date for the Brant Rock/Plymouth demo. However, this proved difficult, due to the unavailability of various players. And to cloud the matter further, word of a similar radiotelephony demonstration in Europe had been received.

Dec. 14, 1906 telegram to R. A. Fessenden:

Impossible to arrange test for Saturday. Mr. Given is in New York. Will try to arrange for next week by having [legal] case postponed.

Hay Walker, Jr.

Dec. 15, 1906 (9:30 p.m.) telegram to Hay Walker:

No use making public demonstration now. Slaby-Arco [German radio researchers] gave public demonstration today using our 1904 method [presumably speech-modulated high-frequency spark or Poulsen arc transmitter]. Associated Press will probably not care for it now.

R. A. Fessenden

Dec. 17, 1906 (1:30 p.m.) telegram to R. A. Fessenden

We still want test [comma] case being postponed. What day will suit you after Wednesday.

Hay Walker, Jr.

Dec. 17, 1906 (3:00 p.m.) telegram to Hay Walker Jr.

Necessary have test Friday as notice too short to get any Guests for Thursday. Very important you advise me earliest possible moment otherwise no guests will be able to be present.

R. A. Fessenden

Dec. 17, 1906 (4:20 p.m.) telegram to Hay Walker, Jr.

Please telegraph date test earliest possible moment, on account short notice guests.

R. A. Fessenden

Dec. 17, 1906 letter to Hay Walker, Jr. (excerpted):

I had taken down the apparatus to make some other tests, but will easily have it in readiness by Wednesday, so would suggest Thursday or Friday for date of test. Everything is working very nicely.

We will not of course be able to get all our guests now, as most of them have doubtless made other arrangements. I think, however, I can get one Bell man and possible Elihu Thompson and I think the Scientific American man.

With reference to Slaby-Arco, this is our old 1903 and 1904 device, and makes a very bad noise in the telephone [headphone] and in addition does not tune well…. It shows, however, what advertisers the Slaby-Arco Company are, as what they have is less than what we had in 1904.

SUCCESS AT LAST!

Finally, the demo was locked in for Dec. 21. No more communication is found in the files until the day after the event (Saturday) in the form of Fessenden’s report to Walker:

Mr. Hay Walker, Jr.

Pittsburgh, Pa.

Dear Sir:

The telephone test Brant Rock to Plymouth took place Friday, December 21st.

Those present were: Mr. Pickard, from the Bell Telephone Company, Professor Elihu Thomson from the General Electric Company, Mr. Read from the American Telephone Journal and two Associated Press men.

Dr. Kennelly and the Scientific American man could not come on account of short notice and previous engagements.

I endeavored to obtain Professor Trowbridge and a Western Electrician man, but the latter had a previous engagement and the former’s wife was seriously ill.

Owing to the fact that all trains were delayed the party did not arrive at Brant Rock until nearly twelve o’clock and after lunch it was two o’clock before the Associated Press man and Mr. Picard started for Plymouth.

The test passed off successfully. With our own transmitters [carbon microphones] an Associated Press man at Plymouth got every word except one which the Associated Press man at Brant Rock spoke. He was not so successful with one of the purchased transmitters [carbon microphones] which was used, though he heard what Mr. Stein and I said on it. The Associated Press man spoke very low, lower than into an ordinary telephone. [The carbon microphone was connected in series with the RF source (the alternator) and, mindful of the RF currents flowing through it, Fessenden had constructed a special unit.]

The Bell Telephone man called us up in the evening and said that the Associated Press man seemed very much impressed with the test. He asked if he could come down again and see me about some further details before making his report to the Chief Engineer of the Bell Company. I told him “yes”, and he was down this morning and spent from ten o’clock to three o’clock with me.

He asked for a lot of particulars, current strengths, resistances, etc., all of which I gave him as they are covered by our patents.

I spoke to him about the trouble with the transmitters, and he stated that in his report which he had already partly written he had stated that the system itself worked absolutely perfectly and uniformly, and that the only variation was the usual one due to transmitters [carbon microphones] packing, and that this was no worse than on their regular lines.

Yours very truly,

R. A. Fessenden

There is no additional correspondence of any kind in the file until Jan. 3, 1907 (a letter from Fessenden to Walker with additional comments about the Dec. 21 demo and the report of the Bell Telephone engineer, Greenleaf Whittier Pickard), so it is presumed that Fessenden took some time off to spend with his family during the Christmas week, also freeing his staff to do the same.

YES, VIRGINIA, IT WAS A CHRISTMASTIME BROADCAST!

In summarizing the events of Dec. 21, 1906, it’s interesting to compare what Fessenden said in his letter (dated Jan. 29, 1932) to Westinghouse’s Sam Kintner, who had written some three weeks earlier to ask if it were true that Fessenden had performed the world’s first radio broadcast near the end of 1906.

Fessenden replied:

“If you mean broadcasting the transmission of speech, music and singing to other stations of the same ownership as the transmitter, then the program given to Dr. Kennelly, Prof. Elihu Thompson and the engineers of the Western Electric and A.T.&T., and other companies, and the editors of several New York News papers [sic] at the exhibition (on 21 December 1906) which you will find described in the American Telephone Journal, Jan. 26th and Feb. 7th, 1907 would be a broadcast….”

Readers will note that this recollection of events more than 25 years after the fact is somewhat at a variance with what happened according to “primary sources,” but Fessenden does declare that he did in fact “broadcast” on that date. And as the transmission was in no way encrypted or sent in a highly directional beam, it does meet the criteria for a broadcast, even though there would likely have been few receivers capable of tuning in the very long wavelength used (6,000 meters) within range of the miniscule ERP (less than 0.2 of a Watt) signal that Fessenden’s apparatus was able to generate then. However, we do know that there was at least an audience of two listening-in as radio was being born: Bell’s Pickard and one of the “Associated Press men” who were stationed at Plymouth.

In reflecting on what happened on that long-ago afternoon of Friday Dec. 21, 1906, there is no doubt that Fessenden planted the seeds which would a decade and a half later germinate into radio broadcasting. This is no doubt either of his intentions, as evidenced by the following typed “handout” presented to those present for the demonstration:

“[Radio] Telephony is admirably adapted for transmitting news, stock quotations, music, race reports, etc. simultaneously over a city, on account of the fact that no wires are needed and a single apparatus can distribute to ten thousand subscribers as easily as to a few. It is proposed to erect stations for this purpose in the large cities here and abroad.”

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING:

- Halper, Donna A. and Sterling, Christopher H., “Fessenden’s Christmas Eve Broadcast: Reconsidering An Historic Event” – The AWA Review, Aug. 2006, p. 119.

- O’Neal, James E., “Fessenden, World’s First Broadcaster?” – Radio World, Oct. 25, 2006.

- O’Neal, James E., “Fessenden: The Next Chapter” – Radio World, Dec. 23, 2008.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to express his thanks to the staff of the State Archives of North Carolina for their assistance in connection with his research, as well the for the granting of permission to publish the Fessenden collection photographs that accompany this article.

James O’Neal is a regular contributor who frequently writes about radio history.