In the summer of 1983, I was working as the chief (and only) engineer of a startup UHF TV station in the panhandle of Texas.

It was a shoestring operation, a spinoff of a more established TV station in a nearby market. The transmitter was a 1970s-vintage RCA, installed in the room adjacent to master control and visible through the large window separating master control from the transmitter room.

Just about everything that aired on that station was on 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape; as I recall, Panasonic machines were used for playout of recorded material.

The transmitter was interesting in that the aural AFC did not work for some reason, and a frequency counter was kept on top of the transmitter cabinet showing the aural carrier frequency.

Several times a day, the operator on duty would have to go in the transmitter room and tweak the aural exciter while watching that counter to keep the frequency within the FCC tolerance.

Guess what we’re doing today

There was, however, a much bigger problem at the station.

From time to time, RFI would cause the videotape machines to behave unpredictably. An operator walking through master control would sometimes put the playout machine into fast-forward. That played havoc with the program schedule and occasionally resulted in missed or botched spots.

The director of engineering and his sidekick from the other market had spent a lot of time trying to cure the problem before I came aboard. Their efforts included covering the roof of the building with copper screen in an effort to create a Faraday cage of sorts. I think the effort actually made things worse, as we’ll see.

Much of my effort in my short tenure there was spent shielding the videotape machines themselves, lining the cabinets with foil and taking other RFI mitigation measures. While this did help, marginally, it didn’t cure the problem, much to my frustration.

One Friday morning, I got to the station to find a handyman, someone the owner used for site maintenance, framing in the garage door. I asked what he was doing, and he told me that we were moving master control into the garage that weekend.

What!? Nobody had said a word to me about it, and I had not done any planning for such a project. Anyone who knows anything about NTSC television knows that it takes a lot of BNC connectors, video cable, audio cable, audio connectors and planning to relocate an entire master control facility, at least if you expect it to work right. And we had none of that.

I called the director of engineering and got confirmation of the project, asking him how we were going to do this. The answer was that we were just going to wing it.

That did not sit well with me. I could see disaster coming and I wanted no part of it.

We had a parting of the ways that day. I have no idea what happened with the master control move or whether it happened at all that weekend.

(The cause of the RFI, by the way, was very likely cabinet leakage from the transmitter, which was just a few feet through the glass from the videotape machines and switcher in master control. By screening the roof, the issue was made worse by reflecting RF back into the building.)

Do your thinking ahead of time

The point of this story is that even as young and inexperienced as I was at the time, I knew that embarking on a big technical project without a good plan was a recipe for disaster.

I’m glad I didn’t stick around. I’m sure I would have been at least partially blamed for the inevitable outcome.

Prior to that episode and following, I was involved in all kinds of projects, from simple studio builds or rebuilds to construction of huge towers and antenna sites, and in each case, there was a plan in place.

With each project, I learned something, usually the hard way. Some omission or something forgotten or not accounted for would result in delays. Something not thought through carefully required a last-minute revision of the plan.

It was always something. And with each completed project, I got a little bit better at planning and thinking things through.

In my company, there is no shortage of projects underway at any given time. As I write this, in the last quarter of 2020, we have several omnibus studio projects in the late planning stages, with equipment scheduled to be on site very shortly.

These projects will be challenging, as we’re replacing cluster infrastructure while having to keep all the stations on the air and generating revenue … at one of the busiest times of the year! (We’re doing this now because we were delayed by several months by the pandemic.)

As I was discussing these projects with our CFO, he made the observation that it sounded like we were going to be changing the tires on a car while it’s moving. Exactly! So how will we pull it off without affecting the on-air product and revenue?

The answer, if you hadn’t guessed already, is to have a very detailed plan that will take us through the entire project.

The plan accounts for every piece of equipment, every wire and every signal in the facility. It really takes all the thinking out of the actual work.

Throughout the decades of my career, that’s the one of the most important things I have learned about project work: do the thinking ahead of time and avoid having to figure things out on the fly.

It’s much harder to think under pressure, and it’s especially hard when you’re tired. A good, well-thought-out plan takes all that out of the equation and makes the project much more of a “paint-by-number” affair.

Such a plan makes a project, big or small, a much more relaxed endeavor. It takes off a lot of the pressure, and while it cannot absolutely guarantee a good outcome, it does greatly increase the likelihood of such.

Stuff happens

So what’s the recipe for a good plan?

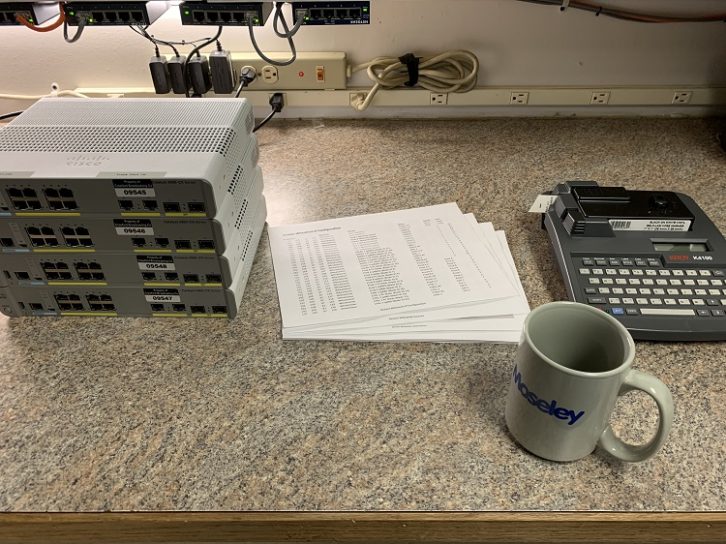

I start with a spreadsheet — a workbook, really, with multiple tabs for different parts of the project. In a studio project, every input and output (or source and destination in AoIP parlance) is accounted for and assigned.

Self-laminating wire labels are printed and ready to install. IP addresses are printed on labels to be affixed to equipment as it is installed. Signal names are defined, and default routing is mapped out.

The layout of every equipment rack is planned, and port assignments on Ethernet switches are made. Nothing is left to be decided on the fly.

In a transmitter project, it’s much the same, although in addition to Ethernet and AES cables, there will be coaxial cables to deal with, both high-power and low, and there will undoubtedly be remote control connections as well, hopefully SNMP but maybe discrete control, status and telemetry signals. Think it all through, plan it out and label everything.

Obviously, the time to do all this planning is not on the eve of the actual project. It should be done far enough in advance that the time pressures of the project deadline don’t factor in.

Make allowances for material order and shipment, which means that you should check stock and delivery time on equipment, connectors, wire, etc. very early on and make adjustments as needed.

As with any project, build in contingencies. Stuff happens (with amazing regularity), and you have to be prepared for that.

Prussian Field Marshal Helmut Von Moltke is credited with saying, “No battle plan survives first contact with the enemy.” There is truth to that, but by controlling as many variables as possible, your plan has a much greater chance of success, and that means making allowances for the variables you cannot control.

In my experience, project work is one of the most enjoyable aspects of broadcast engineering — that is, if the pressures and stress are reduced. The way to do that is with thorough planning.

W.C. “Cris” Alexander, CPBE, AMD, DRB, is director of engineering for Crawford Broadcasting and tech editor of RW Engineering Extra.