The author is the owner of Henry Engineering.

From 1974 to 1988, I was director of engineering at Drake-Chenault Enterprises, a California-based radio programming producer. We distributed music format tapes for automated radio stations, as well as producing “feature shows” such as the acclaimed “The History of Rock and Roll” and ‘The Golden Years of Country.”

In 1977 we rebuilt our studios. The rooms required the capabilities of both a radio board and a recording-studio board, so I decided to design and build custom audio consoles.

These consoles also had to be exceptionally reliable. Many of the broadcast consoles of that era were built using what I called “transistor radio parts,” not the rugged components used in past decades.

Our D-C boards utilized “only the good stuff”: Penny & Giles faders, MicroSwitch and Grayhill switches, Bourns rotary pots, API VU meters, etc. The design paid off, as the consoles proved to be precise in operation and exceptionally reliable. There were no component failures even after 10+ years of very heavy use.

In 1981, I decided to design a more traditional broadcast console based on my experience with the DC boards. It would include some features that simply weren’t available on a typical radio station board.

There were three stereo mix busses, and the ability to assign a channel to more than one bus at a time. Each Line channel had a Left/Right/Stereo/Mono mode switch, a very useful feature especially when doing production or dubbing tasks.

There was also a Talkback system, Cue bus, Remote Line Selectors and electronic audio switching. These functions were unheard of on moderately priced “radio boards,” which were simplistic in those days.

I built three prototype units and sold them to KTNQ(AM) and KIKF(FM) in Los Angeles and KMFO(FM) in Capitola.

Audiophile quality

About this time, my good friend Greg Ogonowski was ramping up his company Gregg Laboratories.

He saw one of my consoles and suggested that it might be good for both of us to market the board as a Gregg Labs product. I agreed, and soon we were working together.

We took my original design and made a few enhancements. The third “Send” mix bus changed from being switch-assigned to being a separate mix, controlled with pots. I added a Cue position to the Line channel Mode selector, so a channel could go to the Cue bus without having to move the fader (again, useful during complicated production tasks).

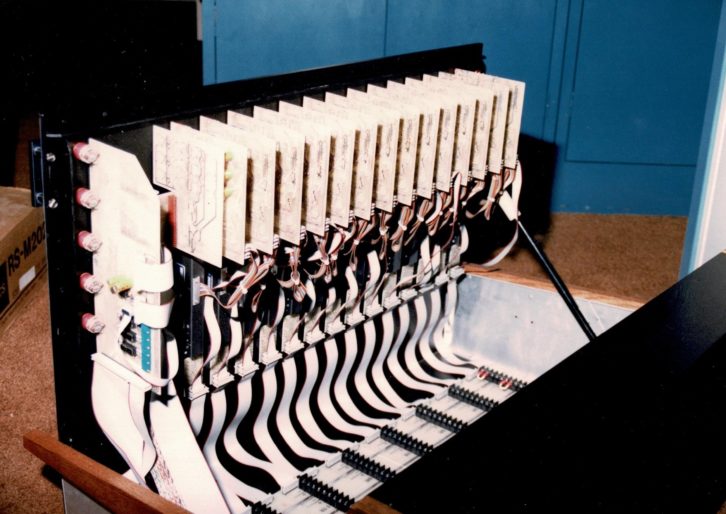

The opto-isolators that I had used for audio switching were replaced with active circuitry, and we used servo-coupled Line, Mic and Output amps to eliminate coupling capacitors in the audio path. The console’s topology was fully balanced but transformerless, another departure from the traditional “old school” design of broadcast equipment.

Greg’s expertise helped me refine the audio circuitry of the product, which bested the typical radio board by an at least order of magnitude. It spec’d and sounded more like high-end “audiophile” gear than typical broadcast equipment, with rock-solid bass and crystal-clear transparent highs.

Even in the days of vinyl, the superb transient response of the Gregg consoles was clearly audible. Greg agreed with my choices of high-grade components and the overall layout and design of the console, so little was changed there. Our internal modular design allowed any mix of Line and Mic channels, but the top panel was solid 3/16-inch aluminum, so that dirt and coffee spills couldn’t get inside and degrade any components or compromise reliability.

In 1983, we began production and sold them quickly. KIQQ(FM) and KNAC(FM) in Los Angeles were some first customers. The list price for a Model 2040 with 14 channels providing 24 input sources was $12,500.

A few of the Gregg Labs boards have surfaced recently and are being restored. The mil-spec pots and switches are still reliable and working well. I’ve joked with their new owners that the Gregg Labs boards included a 40-year warranty, so it’s no surprise that they work and sound just like new!