Somehow, I managed to make it through the first 40 years of my broadcast engineering career without touching or dealing with an FM translator. I scratch my head about that a little bit — how is that possible?

The reality is that for many years, commercial translators operated in one world and full-power commercial broadcasters operated in another, so unless I had done some contract engineering or allocations work for a translator licensee or applicant, there would have been little opportunity for contact across those worlds.

CROSSING THE DIVIDE

That all changed beginning in 1991, when translators were allowed to be used for fill-in service for FM stations, and changed further in 2009, when the door was opened for FM translators to be used for AM station fill-in service (dubbed “AM on FM” by some at the time). Those two rule changes brought commercial translators into the “real” broadcast world and, to some degree at least, breached the divide that had existed between the realms.

Then came AM improvement by way of several translator windows, the first of which opened in January 2016. Since then, there have been three more windows, each of which has seen hundreds of applications filed for moving existing translators (windows 1 and 2) and the creation of new translators (windows 3 and 4)

And so it was that before 2016, I couldn’t even spell “translator,” and now my company has 12 of them (if I counted right), with a couple more in the hopper from the last window, almost one translator for every AM we own.

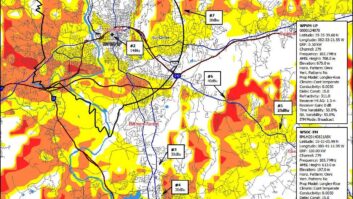

In this 2 1/2-year process, I have learned a great deal about translators — some of it technical, some of it regulatory and some of it practical. For example, I learned that with a clear frequency, a translator can, with just a few watts, cover an entire major market from the right site. Our first translator, K237GG on 95.3 MHz in Denver, continues to amaze me with its market coverage.

I learned that most FM broadcast receivers do a pretty good job of rejecting first-adjacent-channel interference, unless the first-adjacent signals are really strong. As such, a translator can do a good job in an area with first-adjacent-channel signals present. This is even more the case with second- and third-adjacent-channel signals, where even fairly strong signals don’t seem to bother a low-power translator too much.

FUNNY BUSINESS

Working at shared sites, I found that there is quite a bit of “funny business” going on in the translator world — antennas that do not match what is specified on the license, antennas pointed the wrong way and even directional patterns that are reversed.

How do those licensees get away with this kind of thing? It’s simple: Nobody complains, and the FCC’s local Enforcement Bureau folks don’t have the manpower or resources to go around checking this kind of thing in the absence of an interference complaint.

Since I did all our allocations work myself, I had to learn all the ins and outs of the translator allocation world, including how to deal with international borders and cross-border protections. I am thankful that I had Erik Swanson of Hatfield & Dawson to educate me on a lot of this. Erik also functioned as a second set of eyes on some critical protection situations.

The thing that has taken the most getting used to, however, is being on both sides of the translator interference issue. In some markets where my company is the translator licensee, we have had to deal with interference complaints from full-power broadcasters. In other markets, we have had translator applications filed specifying frequencies on which we have operating full-power stations in the same market. So in some locations, I find myself defending against translator interference while in others, I am sorting through listener complaints to figure out which are bona fide complaints and which are not.

That positioning has been a little bit humbling, and it has caused more than a little personal as well as corporate introspection. In this business, I believe that integrity is very important. That means, among other things, that you have to be consistent in what you say and do. I can’t, in good conscience, argue that a certain signal level in one market is not sufficient for a listener to a full-power station to enjoy reliable reception while in another market and situation, arguing just the opposite.

This is where the “golden rule” really comes into play — treat others as you would like to be treated. I have tried to apply that in these translator interference cases, taking proactive and sometimes draconian steps to alleviate interference to spectrum neighbors while hoping that translator applicants/licensees in other markets will do the same.

Back in April, the FCC released a draft of a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that seeks to make some rule changes to better deal with interference protection. Chairman Pai told us this was coming in his address at the spring NAB convention in Las Vegas, and true to his word, a short time later, the draft was released. I very much appreciate the chairman’s transparency and integrity in following through on this and many other things.

As we consider the proposals in this NPRM, broadcasters who are now on both sides of the translator interference issue must weigh the import of translator coverage on one hand and interference protection to full-power stations on the other. I think the NPRM does a good job of balancing these concerns, although I am certain from my conversations with other engineers that some tweaks will be recommended.

CHANGES

In my view, there are three main points in the NPRM. One is a revision of the rules to define an FM translator’s change to any available frequency in the same band as a “minor change” if that frequency change is made to resolve a bona fide interference issue.

Currently, any frequency change of greater than ± three channels is classified as a “major change,” and that requires a special filing window, which we get like broken clockwork every dozen or more years. Allowing translators to move to any open channel in the same band will result in quick resolution of interference issues in many cases. Of course, there may be no available frequency, so this is not a panacea, but it’s a big step in the right direction.

Another main point is a change in the number of bona fide listener complaints from the current minimum of one to six. If you watch the trade press you probably saw that an Atlanta translator was ordered off the air by the FCC in April because of a single unresolved listener interference complaint. Presumably, the proposal to raise the bar to six listener complaints would help prevent that kind of trigger.

The third main point will establish 54 dBu as the signal strength beyond which an FM station may not claim interference, whether or not that station has listeners beyond that contour. You can bet that there will be some comments filed with recommended changes to that number, but it’s probably a good starting point.

The NPRM also deals with a number of other administrative issues, including complaint requirements and listener cooperation with remediation efforts, all in an effort to clean up and standardize the translator interference complaint process and procedure.

With a good number of translator applications still in the pipeline from the Auction 99 and Auction 100 windows, it’s a sure thing that there will continue to be conflicts with full-power stations. This rulemaking is very timely and a great effort to deal with current problems as well as the inevitable conflicts still to come. My hat is off to the FCC for making this a priority.

Cris Alexander, CPBE AMD DRB, is director of engineering of Crawford Broadcasting Co. and technical editor of RW Engineering Extra.