When I started in this business more than 40 years ago, most non-collocated transmitter sites were connected to studios using equalized loops and “dry” copper pairs, both leased from the local phone company. The equalized loop or loops (depending on whether the station was mono or stereo) provided the audio path to the transmitter site, and the dry pair provided remote control, using either a DC and stepper relay or tone system.

This was pretty primitive, but it generally worked — until a pair got wet or a carbon shorted after a storm. That’s when you had hum in your audio and maybe lost your remote control.

Some stations used 950 MHz aural STL links, either mono/discrete or composite. When I went to work as chief engineer of KNUS-FM in Dallas in 1980, that station had a composite over-the-air STL, using a 110 kHz subcarrier for remote control and bringing telemetry back on a low-power 455 MHz telemetry return link (TRL).

What a quantum leap that was over the lease telco line arrangement that I had dealt with up until that time, and how liberating it was to have control of this critical part of the station’s infrastructure. And how odd it seemed to have the Optimod 8100 in the rack at the studio.

Still, there were problems. The path from our 10-story building’s rooftop to the tower at the Cedar Hill antenna farm sure looked to me like it went right through the landmark Southland Life building on the south edge of downtown Dallas, and the receive signal was in the hundreds of microvolts instead of the thousands as it should have been. That made the noise floor higher than it should have been and the station sometimes had a little trouble passing proof (remember audio proofs?).

In the spring and fall, inversion layers would do funny things to the propagation, sometimes giving us grief. As I recall, we had a stereo telco loop as a backup. We didn’t have to use it often, but it was a good thing we had it.

That composite STL/TRL model held up pretty well for a lot of years — decades, really, continuing through the 1990s when digital add-ons could be used to turn composite links into AES transports, getting rid of the noise on such links but adding their own set of issues at the same time.

I tried a set of composite codecs on the completely clear path link from Costa Mesa to Catalina Island and could not get it to work reliably. The receive signal was over 1,000 uV, but evidently multipath from water reflections caused enough distortion in the signal to keep the codecs from locking reliably. It didn’t take long for me to give up on that and go back to the old and (usually) reliable analog composite link.

NEW REQUIREMENTS

Then in the early 2000s, along came HD Radio and that threw a wrench into the works. No longer could we live with the noise that we had to live with using analog links, and we needed a data path to the transmitter site as well for PAD (later PSD).

Some STL manufacturers offered piggy-back data links that would provide a fairly low-bandwidth bidirectional data path in the adjacent unlicensed 900 MHz band, and that was a good interim solution that allowed us to use our existing 950 MHz grid antennas. We took a little hit from the insertion loss of the combiner/splitter, but if the path was good and the frequencies were clear, it worked.

As time went on and technology evolved, however, these low-bandwidth links were quickly swamped. A higher-bandwidth solution was needed. Radio engineers started turning to other alternatives, including unlicensed 2.4 and 5.7 GHz links, and some even employed licensed Part 74 links in the 18 GHz band. And with those changes was the advent of the “connected transmitter site.”

In the mid-2000s, our company began experimenting with the Motorola Canopy and PTP systems on 2.4 and 5.7 GHz, with generally good results. We found that we could get good results as long as we weren’t shooting over center city. It’s true that at times we would have interfering signals pop up for a few minutes or hours, but those generally went away fairly quickly when those responsible found that the frequency they had chosen was occupied and they could not get a link.

Still, we recognized that these links had zero interference protection and would always be subject to being wiped out without notice, not exactly the best situation for a commercial broadcast station to be in. It was then that we started thinking outside the box and exploring Part 101 links in various bands.

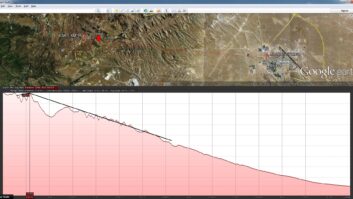

We put our first Part 101 link up in Denver in the spring of 2010, an 11 GHz 14-mile hop. It provided 100 MBPS of bandwidth in a 10 MHz channel. That link is still up and working, and we’ve never had any issues with interference.

Within a few months, we put up two more 11 GHz links, much longer paths but with the same throughput. In 2016, we added a fourth 11 GHz link to our Lookout Mountain site, threading the needle between countless other signals in that band. All four links have been solid. We have since installed Part 101 links in markets all over the nation, some on 6, some on 11, some on 18 and one on 23 GHz. As I write this, I am planning a two-site upper 6 GHz system in New York.

OPTIONS, I LIKE OPTIONS

So what did we gain by “connecting” our transmitter sites? In a word, options. We got options on audio transport — we can use the codec of our choice to get the audio to (and from) the transmitter site. If we choose, we can put processors, importers and exporters at the studio and transport HD data over the link.

We can provide “Artist Experience” data and artwork to our listeners and offer radio display visuals to our advertisers.

We can operate our remote control systems on the LAN/WAN as well as over the public internet for anywhere/anytime access. We can monitor our transmitters through their internal GUIs from virtually anywhere, and they can “phone home” to the manufacturer to report problems before even we know about them.

Site security is much improved now that we can operate our alarm systems and security camera arrays/DVRs over the LAN/WAN.

Even telephone service can be transported over the network. Clusters that have VoIP systems can have IP-connected extensions at the transmitter sites, where our engineers can call local extensions back at the studio or even make long-distance calls toll-free using the included LD bandwidth that often comes with the SIP trunk.

One of our sites has no utilities at all except underground electric power, which we brought in from the better part of a mile away at tremendous cost when we developed the site. That site gets everything over the 16-mile 11 GHz Part 101 link.

Naturally, we have to be prepared for outages. Occasionally a piece of equipment does fail. Last year, we had a nightly insect hatch right in front of the dish on the roof of our L.A. area studio that would attract a flock of birds and take out the link for a few minutes — you could set your watch by it. We fixed that with a plastic owl. Seriously.

In many locations, we have kept the tried-and-true 950 MHz analog, digital or hybrid links as backups, and in others, we have terrestrial internet service as a backup. At the site with no utilities except power, we have a Ku-band satellite link to the site that has saved us more than once.

Still, all things considered, a connected transmitter site is by far the best way to go. Once you move into that world, you’ll wonder how you ever lived without it.

Cris Alexander, CPBE, AMD, DRB, is director of engineering of Crawford Broadcasting Co. and technical editor of RW Engineering Extra.