This issue and next, I’m going to tell the story of building a new, Class B FM station in the noncommercial band. It was a learning experience for me, and perhaps others will benefit from our experience. It was unlike anything I have gone through in many years, and illustrates just how complex our industry has become, especially for smaller or regional operators.

It all began as I was strategizing with my director of engineering and the general manager. We were trying to come up with way to acquire another signal in the Cape Cod region of Massachusetts, and the best I could report was that the likeliest candidate was still hesitating.

“Is there anything else out there we could look at?” asked my GM.

“Well, there’s a guy in Eastham who’s got a Construction Permit who probably won’t build it,” I answered. “He’s only got about four or five months to go before it expires.” We all agreed that we should contact the CP holder just to see what might happen. Two days later, over the weekend, my DoE called me to let me know the CP holder had agreed to sell to us. It was off to the races.

IT USED TO BE MINE

In fact, I already knew this CP very well; it was a prize that had slipped through our fingers during the famous NCE application window of 2007 due to the intricacies of the new Diversity of Ownership rules, also known as 307(b) analysis.

The October 2007 window was the first and only time an application window was opened for the noncommercial portion of the FM band. In the early 2000s, the process of using “windows” to apply for scarce FM channels was put in place to answer numerous court challenges to the previous method of resolving the process of awarding licenses. Because NCE band applications were frozen for more than a decade before the window opened, there was a lot of pent up demand.

The Diversity of Ownership rules were enacted at the same time to provide a framework to decide which applicant would be awarded a Construction Permit in the event that two or more applicants proposed facilities that would interfere with one another (aka “mutually exclusive”). The goal was to make the process transparent and provide a clear method of evaluation so that the FCC staff could allocate Construction Permits without excessive legal or political interference. In fact, this system turned out to work very well, even though the number of applications for new licenses in 2007 was thousands more than expected. The enormous application volume resulted in hundreds of MX situations, some of which involved upwards of three dozen stations, and extended over a thousand miles across several states, but most, if not all, of these were resolved to an eventual winner in a manner that followed the 307(b) guidelines, fully in the public record.

My station filed five applications in the 2007 window and lost each one due to 307(b). The key to winning one was to demonstrate the largest possible population coverage in underserved areas. But of all five, the one I filed for Eastham was the best of the lot and the one that was heartbreaking to lose.

This husky cell tower capped off at 196 feet and thus did not require lighting or registration. It was my “secret” weapon in the search for a site to serve Cape Cod during the 2007 NCE application window and later became our only option as we looked for ways to build out our about-to-expire Construction Permit.

STEALTH SITE

The location of the Eastham application was one that Doug Vernier (our consultant) and I discovered during a hunt for available frequencies for non-commercial stations in 2004. The trick about Cape Cod is that NCE channels had been suppressed in that region since the 1960s when the FCC enacted rules to protect television Channel 6 stations from interference. Those protection rules were so far-reaching that the Channel 6 TV station in Providence, R.I., had prevented any significant-sized NCE stations for decades across the entire cape. But there was a sliver of land to the very east of Cape Cod that was just far enough away to allow a new, mostly vertically polarized station of significant power to be built in the towns of Eastham or Wellfleet.

Although at that moment, the FCC still had a freeze on new applications, I made a physical survey of the area to investigate further. There were no towers in the FCC database for either Eastham or Wellfleet. In fact, zoning regulations specifically prohibited all tower construction on any private land in either town. But I discovered that in 1998, an unregistered cell tower that was just under 200 feet tall had been built on town land in Eastham. On the flat Cape that was enough height for an FM station. I kept this to myself and waited for the 2007 window to open.

THE BEST LAID PLANS?

Unfortunately, as it turns out, I wasn’t the only one to notice there was some available “white space” in the Eastham region. When the smoke cleared from all the applications filed in October of 2007, our application was part of an “MX string” that stretched from one end of the Cape to the other and included 16 stations. Many of these applications violated the FCC Rules and would be dismissed summarily in about six months. However, under 2 miles from our “secret” site, another consultant had filed for nearly identical facilities in the backyard of a church. Their application proposed a 100-meter tower be built.

I went through all the aspects of the 307(b) analysis and found that our two applications were both the best in the MX group and virtually identical. In other words, the award would be determined by what were known as “tie-breakers.” And here is where the “diversity” rules delivered a fatal blow: The other applicant had no other radio station licenses. As a license holder, my station would be rejected as “not providing diversity.”

Even though we knew that the opposing applicant’s tower could and would never be built, we were left without any means of objecting to the eventual award of the CP. And in fact, about four years later, that’s exactly how the MX group was resolved by the FCC without our being able to make even a peep of protest that our proposal was the only one with an actual construction chance. And we gave up hope of ever acquiring this station.

IT ALL COMES TOGETHER

Back to last December, we were at first elated at our good fortune and then sobered by the amount of work it would take to build out a new station. While the CP was potentially within our control, it still needed to be amended to a workable tower site so that we could file for a minor modification with the FCC. The deadline to complete was April 15, a few short months away, but very doable.

My first step was to do a search of the FCC tower database to locate all possible tower sites in the area. This turned up four possible candidates. After a few phone calls, we were down to just one tower with sufficient capacity, a 450-foot mixed-use facility. At the same time, I still recalled the Eastham site from 2007, although a change of ownership hid it from my search and it appeared to no longer exist.

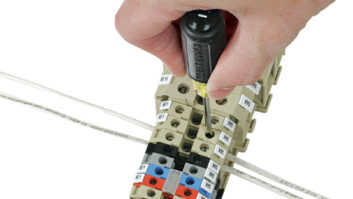

We took a tour of the 450-footer and liked the site immediately. I ran the engineering to develop coverage contours, using V-Soft’s FM Commander, and we got back very encouraging coverage contours. With this in hand, I began to prepare the application exhibits for the FCC and we began negotiations for a lease. I also began to put together a list of equipment orders that would be required, as I knew we might need to request delivery of items at a faster speed than usual. For our main broadcast items, I alerted our sales contact at Harris Broadcast (now GatesAir) about the need for a transmitter. I also began discussion with Shively Labs about modeling a four-bay FM antenna. Finally, I reserved time with our tower contractor, Broadcast Tower Service, to make sure they would hold time for us in early April. I built the critical gain budget, which determines the size of transmitter required, transmission line size and efficiency, and number of antenna bays required to make the proposed ERP. It all was coming together until something funny came back from our lawyers as they prepared to file the minor modification request.

Map showing a comparison between original Construction Permit and the proposed Minor Modification to show 307(b) compliance. Although our proposal would appear to provide nearly identical land coverage to the original CP, the FCC staff was unable to proceed with our application without a waiver request. Both contours are limited by the same 1st-adjacent channel station, but our location was just sufficiently different from the original to detract slightly from the 1st and 2nd service areas.

THINGS FALL APART

It was that devious 307(b) analysis that was coming back to tease us. When our legal team looked over the engineering exhibits, they warned me that it looked like we weren’t covering all the geographic area that the initial CP had been awarded.

“You mean that 200-yard-wide strip of beach sand up above Provincetown?” I asked. “There’s no one that lives there, and besides our proposed site delivers even more unserved population than the original and that should outweigh whatever we miss up there,” I added. But I was dead wrong.

It turns out the FCC staff takes the award of a CP under the terms of 307(b) very seriously indeed, and they expect the holder to build out exactly what was awarded. No deviations allowed. At first we didn’t believe the FCC staff would hold out for a signal in the sand, but as we did further research, the case law showed that, in fact, many such proposals to modify 307(b) stations had already been turned down. Ours was a relatively minor deviation, but they would only consider it if we formally requested a waiver and justified the change. Unfortunately, the FCC staff stated from the beginning that “failure to consider if a site can be used to build a tower” is not sufficient reason for a waiver. Uh-oh, that was precisely why we needed a waiver! Apparently this wasn’t going to be as easy as we thought.

As if this wasn’t enough, a few days later, the owners of the 450-foot tower site changed their minds and realized they had made a mistake. They had no space to rent due to a previous commitment and, therefore, we could not consider this, the only tower that had any capacity, as a possible site. This happened the first week of February. Our project was in shambles and time was running out.

It may not look like much but to me this was pure gold. This shelter space was vacated by a cell operator and left with a complete electrical system intact, ready for us to patch, paint and move in our equipment. The room also included two air-conditioning units, still in working condition.

ONCE MORE UNTO THE BREACH

While the bad news kept coming, I finally had a bit of luck and discovered the new owner of the old Eastham site from our 2007 application. It turns out the tower had been acquired by Crown Castle, a company we already leased space from on another tower. Luckily, the exact same location on the tower that we used for our 2007 application was still available, and as it happens a cell carrier had just vacated a room in the shelter below the tower. This site could be built quickly because all the electrical service and power distribution was still in place for a transmitter room, including two working air-conditioning units. This site could save me four to six weeks of construction time — but we still would have to make it work with the FCC.

I recalculated all the engineering and again wrote up the exhibits needed for the FCC application. Because this site was just a mile or so from the site on the CP, I thought we should be able to make an argument that we were doing everything in our power to build according to the terms of the 307(b) award. But in the end, it took five weeks before we got the green light — even this site required a waiver in the eyes of the FCC.

And that’s how I ended up with three weeks to build a Class B FM with 42 kW of ERP! I’ll tell the rest of the story in Part 2.

Michael LeClair is chief engineer for radio stations WBUR(AM/FM) in Boston; he has been technical editor of RWEE since its inception in 2005.