Fig. 1: The lone tree in a field usually marks an anchor point. Long-time readers know that when we see a picture of a lone tree in a field, usually guy wires and an anchor are hidden within.

Figs. 1 and 2 are no exception. I’m not sure why bushes and trees like to grow around tower anchors; maybe it’s because the crew mowing the field won’t get that close to the guy anchors to keep the brush down, which is probably a good thing. Bush hogs and anchor points don’t mix.

Fig. 2: Reduce rust and potential damage to anchors by keeping brush trimmed. So the job may fall on you, lest a forest grow around the anchors. Here are useful tips as you tackle the problem.

Hand trim bushes, cutting the trunks off at ground level. Use caution in applying chemicals to kill the roots, until you are sure there will be no effect on the buried anchor. Ditto for digging up the roots.

The problem can be exacerbated when a briar patch grows around the anchor. Yes, there is an anchor hidden in Fig. 3. But those thorns are sharp, as seen in Fig. 4; tackle them with heavy gloves and lopping shears.

Fig. 3: Can you find the anchor? A snare of weeds buries it. Don’t leave the cut branches on the ground; they can encourage nesting. Instead, grab a pack of those heavy paper lawn bags — the branches won’t poke through, making transport easier.

After removing the growth, carefully inspect the anchoring system for rust, corrosion or any other compromise of the anchor point. It’s not a bad idea to take a digital photo, just to document the condition.

* * *

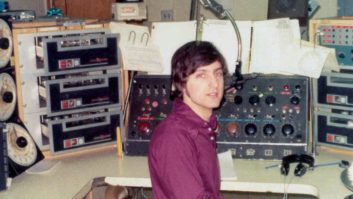

Margaret Bryant was reading in the Oct. 8 Workbench about labelling UPS units and offered a useful comment. When she was at ABC Radio Networks in Dallas, they had one large UPS serving all of the studios and the Technical Operations Center. In addition, there were several smaller supplies scattered around.

Fig. 4: Brambles can make removal especially difficult. The breaker boxes were labelled with what every breaker was and how they were fed. Some were utility-only, some generator-only and some were UPS and generator. The boxes that were UPS fed had extra labelling, which was a color code indicating a priority.

The color code was for load shedding — in the event of a generator failure, the UPS batteries are only going to stay up for a certain amount of time. The idea with the priority color code was to extend the amount of time as much as possible by shedding whatever load they could. It was an easy-to-read color code, indicating which studios could be shut down to prolong the amount of time remaining on the batteries.

Margaret adds that she’s not sure if the system was ever used, but in theory it would provide additional on-air time.

This is the kind of forward-thinking for which broadcast engineers are known. In the midst of a catastrophic electrical failure, load shedding is probably one of the last things you’d think about. Better to come up with a plan in advance of the problem.

It’s neat to see that Margaret still keeps tabs on broadcasting through Radio World, especially when absorbed by her other passion: pet photography! Looking for a portrait of your pet for the holidays? Head to Margaret’s site and enjoy the talented photo gallery at www.bryantdogphotography.com. She can be reached through the site.

Fig. 5: Plug conduit openings like this one to keep out the elements — and worse.

* * *

While you’re at your transmitter site for the grounds keeping we mentioned earlier, check the integrity of above-ground conduits, such as those used to run satellite cables inside the studio or transmitter building.

Fig. 6: Open conduits invite nests.

Fig. 5 shows a conduit inviting failure. The wide opening will serve as a drain for rain or snow — if the rodents don’t get there first. The water-filled conduit then freezes and cracks; and the cable may be damaged. At the least, trying to replace cables in an ice-filled conduit is not an experience to be repeated. Even though open horizontal runs may not serve as drains, they are a welcome sign for rodents, as you can see from the nesting material in Fig. 6.

Plug conduits with a tight-fitting plastic cap or a combination of stainless steel or copper wool and expandable foam. The foam provides a weatherproof seal (which can be removed), and the metal wool thwarts rodents. Tying a string or wire around the wool plug will make removal easier, if cables have to be replaced or added in the future.

John Bisset has worked as a chief engineer and contract engineer for 40 years He recently joined Nautel as Regional Sales Manager for Europe and Southern Africa . In 2007 he received the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award. Reach him at [email protected]. Faxed submissions can be sent to (603) 472-4944.

Submissions for this column are encouraged and qualify for SBE recertification credit.