Journalists have used Smartphones for nearly 10 years, to create content for radio, online and social platforms and — as the cameras and associated apps have improved — for TV. As mobile journalism becomes more widely used, universities and colleges are building “Mojo” into formal journalism degrees.

Corinne Podger demonstrates a mobile reporting app to student, Shantelle-Ann Marquis.

Photo Credit: Andrew Brain.

The first to do so here in Australia was Macleay College, which added Mojo to its first year Journalism BA and Diploma in 2015. I taught Macleay’s BA Journalism course throughout 2017. Over a 12-week term, students learned mobile photography, video shooting, social and TV package editing, podcast creation, and live streaming.

To keep course materials and tools up-to-date, I consulted journalists around the world about their work to integrate mobile content into newsroom workflow. It’s been a fascinating journey into an evolving landscape of story production. Here are some of the key lessons I learned, for educators and newsrooms keen to increase their Mojo output.

1. Journalism apps are not toys

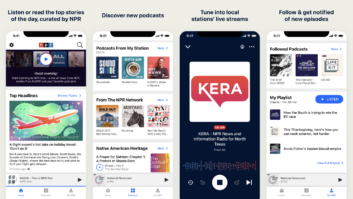

There are dozens of photo and video editing apps for mainstream consumers, which are quick and intuitive to learn.

But professional apps designed specifically for journalists are complex pieces of software that happen to run on a mobile device, and they take time to master.

Like Filmic Pro (IOS/Android), a powerful video capture app that gives manual control over frame-rate, color temperature, focus, exposure and white balance, and even allows you to shoot in ‘LOG’ mode.

Or Luma Fusion (IOS only), which aims to replicate many of the functions of desktop editing systems like Final Cut or AVID. Or Ferrite (again, IOS only), which turns your smartphone into an audio craft-editing suite for making radio shows and podcasts.

Is it worth it? Well, Eleanor Mannion of Irish broadcaster RTE used Filmic Pro to shoot a one-hour television documentary, The Collectors, in 2016. Fellow RTE journalist Hiromi Mooney uses Filmic Pro to shoot, and Luma Fusion to edit, stories like this.

So if teaching newcomers to audio-visual journalism, by all means start with basic apps to cover off the fundamentals, but in a longer course you can cover high-end apps and create immediate opportunities to put new skills into practice.

2. Choose the right kit for the job

There’s a growing range of mobile journalism equipment – tripods, lenses, gimbals, drones – and it can make a big difference to the quality of your output.

Much of it isn’t cheap, though, and once you hit the 2,000 euro mark, you’re into the range of an entry-level television camera.

So rather than buying the latest shiny stuff, choose equipment based on what your audience needs from you. Do you want a few high-end mobile journalism kits, or do you want every journalist to create smartphone content?

Whatever you decide, the basic minimum is necessary to overcome the three big giveaways of amateur video: shaky footage, digital noise in still images and low-light footage, and poor quality audio. That means a tripod and tripod mount, an external hand-held or clip-on microphone, and an external light and fold-up reflector for indoor work.

Incidentally, research earlier this year found interviewees feel less daunted talking to a smartphone than a big TV camera – but they don’t regard the smartphone as a serious tool either.

My students found the same was true when interviewing in the streets of Melbourne, but putting the smartphone on a tripod made it look like a ‘real’ camera and got rid of the problem.

Corinne Podger

3. The most common errors cost nothing to fix

We wouldn’t dream of putting a high-end DSLR in a dirty bag, let alone pulling it out and starting to film without cleaning the lens, but our phones live in pockets and backpacks and we touch the lens constantly.

You can avoid cloudy, misty footage by using a glasses cloth to clean the front and back lenses of your smartphone before you start filming or taking photos.

Another common error is failing to lock focus and exposure before starting to film. On an iPhone this is as simple as holding your finger on the screen until a yellow ‘AE/AF LOCK’ box appears. If you do this – for every single shot – your subject will always be in focus and your exposure will stay constant throughout the shot.

Lastly, many of my students – on both IOS and Android – found that smartphone footage can drift out of sync with the audio. This problem gets worse the longer you shoot, and it’s particularly obvious in interviews.

Some desktop systems – like Premiere Pro – seem to compound the problem.

If you stop and re-start filming on longer interviews every six to eight minutes, you can minimize syncing problems, and if you’re using a desktop system to edit your footage, Final Cut Pro seems to be the least vulnerable to introducing additional audio lag.

4. It’s all about the workflow

There are two further operational questions to explore when choosing apps and kit, so that the content produced by reporters can be integrated into existing newsroom workflows, which may include standard file formats and house styles for fonts and images.

First, is the content destined for broadcast on television or radio, or will it live primarily online and on social platforms? And second, can you invest in smartphones and apps for all your reporters, or will you expect them to use their own phones and buy the apps themselves?

Let’s take video as an example. Video that is destined for TV needs to take frame-rate into account. In PAL countries — which is most of Europe and in Australia — that ideally means filming at 25 or 50 frames a second (fps), not the 30 or 60fps that is standard in NTSC countries like the United States.

The iPhone native camera shoots at 30fps, so European TV journalists need a video capture app that allows manual framerate adjustment, like Filmic Pro or Kinomatic.

The editing system you use also needs to be PAL or NTSC-compatible. Luma Fusion and Kinemaster are two editing apps that can save a finished PAL-compatible file, but Luma Fusion is the only video editing app that will import external fonts for captions and supers – and it’s IOS only.

So if you’re willing to buy a set of iPhones for TV production, great. One media outlet that has done this is Omrop Fryslân in the Netherlands.

Coordinator Wytse Vellinga says this helps the newsroom keep operating systems up to date, install a curated list of apps and train journalists to master their use – and to rely on desktop systems primarily for transcoding edited videos for television broadcast.

Otherwise, journalists will be using a combination of IOS and Android phones. If that’s the case and your media outlet has standard fonts for captions and supers, the most effective workflow for television is to film on a smartphone and then switch to a desktop system like Final Cut or AVID for editing, adding supers and captions, before rendering off a master.

Video that will live purely on social media or on a website can effectively ignore television broadcast file formats, so the workload may be as simple as capturing, editing and posting video using a single app like Apple Clips. One example is this British general election wrap from RTE journalist Patricia O’Callaghan.

One other tip here is to keep an eye out for updates of apps your team uses regularly, and run a quick refresher class on new functions and workflow if a go-to app gets a major overhaul.

5. It’s all about the story

You can invest in all the high-tech kit and apps you like and still churn out bad content if the storytelling isn’t solid and told with a clear target audience in mind.

So mobile journalism training needs to cover journalistic basics, such as writing for pictures, filming for the edit, scriptwriting and presentation skills.

It also needs to cover the creation of the content that goes with a piece of audio or video to make a finished piece of journalism, such as engaging social and online headlines and well-written text and social posts.

What does great mobile journalism look like in practice? Two examples of TV journalism shot on smartphones include this piece about one of the world’s oldest Planetariums by Omrop journalist Wytse Vellinga (shot on Filmic Pro, edited in Luma Fusion), and this story by RTE journalist Philip Bromwell about ancient Irish manuscripts (shot on Filmic Pro, edited in Luma Fusion).

Where Mojo really comes into its own is on social platforms. This piece by BBC journalist Dougal Shaw about a suburban street that closes to allow children to play (shot on Filmic Pro, edited in Final Cut Pro X and saved in the square format that’s perfect for Facebook) has racked up more than 10 million views since it was uploaded two months ago.

Another example is RTE’s Digital First stories, all of which are filmed and edited on smartphones, and are optimized for social distribution.

Responding to research that suggests stories that engage us emotionally are more likely to be shared on social, the team has focused on covering deeply personal stories like this piece about crocheted octopuses for newborn babies, which has received over 5 million views on Facebook — compared to a maximum of around 50,000 views for a story lifted straight from a TV bulletin.

Philip Bromwell, who is leading the project, says the videos are shot on Filmic Pro and edited on Luma Fusion — so they can be transcoded for television broadcast – but are also saved from Luma in formats that suit different social platforms – landscape for Twitter, and square for Facebook and Instagram.

6. Mojo as a newsroom bridge-builder

Big multimedia newsrooms are full of silos, especially at broadcasters, where television, radio and online producers often work in separate spaces or offices. They may all have social media posting duties, or there may be a social media desk adding yet another silo to the workplace.

Mobile journalism cuts through all these divisions, because the device itself can produce content for all these platforms. The smartphone is a television camera, a radio mixing desk, a video editing suite, a stills camera, a podcast creator, an infographics and chart generator, and a device for having conversations — with interviewees and directly with the audience.

So it can knock down the walls between different content creation divisions — and this can be taught easily in a post-secondary setting.

After all, my students already use their phones for budgeting, watching movies, finding a rental, booking a restaurant, choosing a date and looking for a job. It’s the perfect device teaching them the multiplatform digital mindset they’ll need in the workplace.

7. Top app recommendations:

Video shooting: Filmic Pro (IOS and Android)

Video editing: Luma Fusion (IOS only), Kinemaster (IOS and Android)

Audio recording: Voice Record Pro (IOS), RecForge Lite (Android

Audio editing: Ferrite (IOS only), Audio Evolution Mobile Studio (Android)

Stills photography: VSCO (IOS, Android)

Photo editing: Snapseed (IOS, Android)

Corinne Podger is a journalism teacher, lecturer and smartphone storytelling consultant who has trained for Reuters, BBC Media Action, Fairfax Media and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Contact her via email at [email protected] / [email protected]; or send her a DM on Twitter: @corinne_podger, LinkedIn

This article was first published by the European Journalism Observatory.