A Technical History of WHAV

Aug 1, 2010 1:00 AM, By Tim Coco

Sign Off, Aug 2010

When the Haverhill Gazette opened its new WHAV studio building to the public in December 1947, it was an exciting weeklong event. Business people, potential radio time buyers and finally the public were allowed to tour the art deco-styled building. The special week concluded with a live appearance by popular vocalist Vaughn Monroe.

WXRV, the former WHAV-FM, continues to occupy the building to this day. WHAV (AM) left the building upon its sale in 1995.

The new studios were designed by local architect Clinton F. Goodwin and were clearly built for live entertainment — a style that was about to be upset by television. A copy of the original blueprints remained in the chief engineer’s office for at least 30 years. Goodwin confided to me before his death in the early 1980s that he toured other stations, including WEEI, Boston, to determine how best to design the studios. Since few stations were built from the ground up during World War II, he largely copied 1930s radio buildings. Construction was undertaken by William H. Starbird, a local contractor.

WHAV Program Director Warren Greenwood takes an airshift from the main control room in June 1948.

The station actually signed on March 16, 1947, but operated from temporary studios above a downtown bank while the new building was completed. Construction was delayed both by a lag in receiving permission from the post-war U.S. Civilian Production Administration and a protest by the AFL Teamster and Chauffeurs Local against the non-union Starbird, according to stories that appeared in the Haverhill Gazette.

Visitors during the open house week in 1947 found a square two-story (two and one-half in the rear), white stucco building with masonry glass windows — one on each side of a large triple-beveled entrance. Because the building was built into a side of a hill, the entrance consisted of two large glass doors and then stairs to the second floor of the building. WHAV’s name was engraved in a granite-like floor and also appeared in a neon-lighted sign that rose above the building. Incidentally, I was the one who discovered the shattered glass door when I arrived for my early morning airshift sometime during the late 1970s. I urged one of the owners to restore the door, but he opted for a more secure mostly metal door. The aesthetics have been compromised since.

Once inside, through the doors at the top of the stairs and into the pink granite-floored lobby, visitors probably first noticed the glass window on the left side of the wall ahead of them. This looked into the building’s impressive large studio. While waiting for the tour to begin, guests had a chance to take in the happenings all around them in the lobby. Looking back toward the entrance they would have seen the door of General Manager John T. “Jack” Russ’ private office on the right. The remaining offices on the left and right were behind a half-high wall of clear varnished wood veneer, topped with a textured glass within stainless steel frames for privacy.

A center opening in the left wall appeared where a quarter round receptionist’s counter jutted into the lobby. The receptionist probably asked guests to be seated while she answered calls on the new, free-standing Western Electric 551 switchboard. Those paying attention would notice much of the station was outfitted by Western Electric. The manufacturing arm of AT&T obviously won the loyalty of the station since the company operated a manufacturing plant in the city.

Across the lobby in a similarly styled bank of offices, the clickety-clack of the Associated Press teletype machine can be heard over the half walls. A built-in bin collects the rolls of imprinted yellow paper. Other offices off the lobby housed the commercial manager, program director, continuity writer and schedule supervisor.

The studios

As the tour begins in earnest, the door to the right of the large studio window opens out, exposing a short, sound-proofed hall. Besides the large studio on the left, a door ahead opens into a small announcer’s booth. The door on the right opens into a smaller version of the large studio. Most of the interesting elements in 1947, however, were largely on the left side of the building. It seems the right studio and control room above it were reserved for the forthcoming FM station.

In the large studio, about two stories tall, visitors take notice of the 12×12 straight drilled acoustic tiled-lined ceiling and walls, interrupted here and there for half round wooden tubes to help shape the studio’s acoustics. It looked something like photographs of the CBS studio Orson Welles used to broadcast the War of the Worlds in 1938. The linoleum floor features cut-in colored shapes and what appears to be a path to the rear door of the studio. The room is well lit from two bands of fluorescent tube lighting in the ceiling. In the rear is the requisite grand piano. Above it is a large round clock and a built-in monitor speaker. A window angles in over the room from about a quarter story above, where the control room is located. Another window to the announcer’s booth appears on the right, closer to the entrance.

— continued on page 2

A Technical History of WHAV

Aug 1, 2010 1:00 AM, By Tim Coco

Sign Off, Aug 2010

The only obvious audio input equipment is a Western Electric “bird cage” 639 cardioid microphone, mounted on a floor stand. Another one is mounted on a boom and both plug in to the wall. Two years later, Altec Lansing Corporation would take over the production and servicing of these mics.

A black Stromberg Carlson, 12-button intercom telephone appears below and to the right of the control room window. An external light mounted above the phone replaces the internal buzzer. The telephones seemed to have been used in all studios, control rooms and transmitter building. The sets appear to pre-date the station and may have been purchased used since many products remained in short supply after the war. The cradle of the phones could be mounted on top for wall use or on the face of the unit for desktop use.

The studio’s rear door leads into a hallway. There are both steps to the lower level and a shorter set up to the control room.

Control rooms

Through the door at the top of the stairs leads to a small open area with several 19″ equipment racks and two control rooms. The racks contain patch bays and a World War II surplus monitor amplifier that feeds control room audio to the studios below. Interestingly, the amplifier’s manual contains instructions for cutting all wires and smashing tubes to prevent its use by the enemy. Chief Engineer Herbert W. Brown was hired before construction began and likely helped make the equipment selections.

The new transmitter and tower site in 1947; the mast is reserved for the FM bays, added about a year later.

There is a space between the control rooms and each has a window facing the other. The open space between the studios ensured no sound leakage. Publicity photographs from the time center on the control room overlooking the large studio.

Compared to years later when magnetic tape would come on the scene, few pieces of input equipment appear in the control room. The new Western Electric 23-C five-pot studio console is fed only by a 639 cardioid microphone in the room, plus those from the studio below. The console is in the center of a U-shaped wooden desk, covered with red linoleum with stainless steel side trim.

There are three Rek-O-Kut 16″ transcription turntables — one on the arm to the right of the mixer and two on the left. These turntables play only 33-1/3 and 78RPM discs. There must be a disc recording lathe somewhere in the building, but its location isn’t obvious.

Like the lobby, walls are covered halfway up by a wood veneer with a clear varnish. Instead of straight-drilled tiles, the upper walls are finished in a smooth acoustic, wood-fiber tile. Unlike the large studio, lighting is indirect, with incandescent bulbs hidden in a wooden trough near the ceiling. Incandescent bulbs were considered a quieter option in smaller spaces of a radio station. A monitor, built in an angled wooden frame with fabric wrapped around the speaker, appears above.

Under the lower, right arm of the built-in desk is a steel 19″ rack frame with a series of double patch assemblies. These were used to route audio in and out of the control room. A simple on-air light consists only of a bare red bulb in the studio window.

— continued on page 3

A Technical History of WHAV

Aug 1, 2010 1:00 AM, By Tim Coco

Sign Off, Aug 2010

The other control room was similarly constructed, but its early equipment complement is not known. From this room, it was possible to look down into the announcer’s booth as well as the smaller performance studio. An announcer’s bathroom completes this level. It features the only window to the outside in this part of the building and became useful for announcers checking weather conditions outside.

Below, the first floor contained public restrooms, record storage areas, an announcers’ lounge and the chief engineer’s office and work area.

Transmitter building

While the studio building was largely outfitted by Western Electric, the transmitter building a few miles away atop of Silver Hall was initially equipped by Raytheon. Raytheon operated a manufacturing facility (and still does) a few miles outside the city.

Visitors peer into the large studio from the lobby window during an early tour of the new building.

At the Silver Hill site, a three-legged self-supporting tower (later guyed) was erected. Its first 160′ was designed for AM transmissions at 1490kHz, while an isolated 80′ mast on the top was reserved for later FM transmissions. The transmitter building contains a large open area on the left for AM and FM transmitters and audio processing and monitoring equipment.

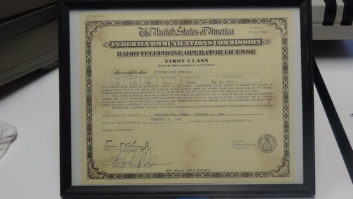

In the days before remote control and metering were allowed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the right side of the transmitter building contained a bedroom and bathroom for the engineer on duty and a work area with benches.

The first AM transmitter was a Raytheon RA-250, 250W model. It was brown and tan in color and featured 12 external meters on two rows at the top of the cabinet. The transmitter used a 655 crystal oscillator, 807 buffer amplifier, 813 RF driver amplifier and two 810 tubes operating in push-pull as a power amplifier. This transmitter served as the main until at least 1960 and took on backup duty until the mid-1970s. I helped the engineer ready the unit for reuse on the amateur band in 1978 or 1979.

Two tall racks sit to the right of the transmitter with a ceiling-mounted, angled wooden box for a monitor speaker. A limiter, modulation monitor, frequency monitor, monitor amplifier and patch bays were installed in the racks, but their brand names have been lost to history.

WHAV-FM finally went on the air April 14, 1948. The station occupied 92.5MHz on the dial. Its first transmitter appeared to be a Western Electric 506B-1. It fed 10kW to the bays.

“FM broadcasting opens a new era for radio in Haverhill. It will give WHAV a second voice and will reach out into homes within a 50-mile radius of the city,” The Haverhill Gazette announced.

— continued on page 4

A Technical History of WHAV

Aug 1, 2010 1:00 AM, By Tim Coco

Sign Off, Aug 2010

1950s and the advent of 45s

Pressure from television, restrictions on simulcasting and a declining local economy took tolls on the operation of WHAV AM and FM. In an effort to control costs, the Haverhill Gazette invested in two of the newly introduced Presto 10.5″ reel-to-reel decks. As debts mounted, former News Director Edwin V. Johnson told me, most of the staff was released. That left Johnson and weatherman Earl “Bud” Smith recording and playing all taped programs 10 hours a day.

Chief Engineer Herbert W. Brown was provided this car for trips between the studios and transmitter building.

WHAV-FM was dark by 1953 and its transmitter was purchased by WCRB. The virtually insolvent WHAV-AM was sold in 1954 to Edward I. Cetlin and Henry R. and Morris Silver. The Silver brothers were owners of a successful Manchester bottling company and former owners of WFEA, Manchester, NH, and WKXL, Concord, NH.

Since the Rek-O-Kut turntables could not play the new 45RPM records, the new owners purchased new Gates CB-500 16″ transcription turntables. These were equipped with wide Gray-brand tonearms. At the end of the decade, and free-for-the-asking, a 20kW WHAV-FM was revived at the 92.5MHz frequency. The transmitter type is unknown. It was probably about this time, the station added a Gates Studioette four-channel monaural, tube-type console back at the studios. It would remain in active service until the early 1980s.

1960s power increase

When the FCC allowed local Class IV stations to use 1,000W power days and continue 250W at night, WHAV purchased an RCA BTA-1R1. The new transmitter used 4-400A tubes for its power amplifier and modulator.

In the years that followed, and with the evolution in technology, several early RCA RT-7B rack-mount cart machines entered the studios. There was one RCA BA-7B record amplifier. One RCA 4-cart automatic machine also went into regular use. At some point a pair of Ampex 351s full-track transports replaced the aging Presto machines.

At the transmitter building, a CBS Audimax was put into service on the AM and a CBS Volumax on the FM. They remained in back-up service at least until the early 1980s.

1970s stereo and solid-state

Stereo did not come until the 1970s for WHAV-FM when it aired the “Music Just for the Two of Us” instrumental format from Peters Productions, eventually employing a Schaefer automation system. An updated Schaefer was eventually added and the two systems were nicknamed “Trixi” and “Norton” respectively after the “Honeymooners” characters. A keypad using only ones and zeros was used to program the later device.

Three reel-to-reel decks and two cart carousels were used. Originally, Revox B77 decks were used, but these proved troublesome as they slowed and often stopped while trying to rewind the 10.5″ reels. I can’t recall what replaced them, but ITC decks come to mind.

— continued on page 5

A Technical History of WHAV

Aug 1, 2010 1:00 AM, By Tim Coco

Sign Off, Aug 2010

At the time, a Gates FM-10H 10kW transmitter powered the FM. A power increase to an effective radiated power output of 50kW using a Gates FM-20H3 was partly financed by a Rhode Island station on an adjacent frequency as a condition of its own power increase, according to a former chief engineer. An Optimod 8000A processed audio — still carried between the studios and transmitter by telephone company equalized lines.

A trade ad placed by Western Electric touts the installation of equipment at the new radio station. Click to enlarge.

Several disasters took the FM off the air for days at a time while I was there in 1979. First, vandals pierced the coaxial cable while trying to take out the tower lights with rifle shots. Water eventually entered the cable. Later, what seemed to be a routine move by an operator at the studio to rotate the antenna switch by remote control to place the now-backup FM-10H on the air turned into a crisis. The antenna switched was not interlocked and allowed the FM-20H transmitter to remain powered up while not actually connected to the coax. The Andrew switch burned and melted, and the transmitter building filled with smoke. I helped Chief Engineer Ted Nahil bolt together sections of spare coax “plumbing” and create a direct path around the destroyed switch between the backup transmitter and tower. The FM-20H was not seriously damaged and was restored within a few weeks when the new antenna switch arrived.

In defense of the operator on duty at the studio, the remote control with only “raise” and “lower” switches often got out of sync with its sister device at the transmitter and created confusion.

Stereo required retrofitting the studios. A Gates Executive 10-channel stereo transistor console was purchased for the FM. At first, it occupied a new desk sitting in the large performance studio. Later, it was moved to the small announcer’s booth where a new Scully stereo reel-to-reel joined the complement.

About the same time a dual-channel Gates Diplomat board forced the retirement of the Western Electric console on the AM station. New Gates CB-1200 turntables with stereo Micro-Trak tonearms were added to the main AM control room now above the small studio. Gates solid state preamps are mounted under the desk. The RCA cart machines were replaced with the Gates Criterion series. The older control room, now largely used only for the nightly Open Mic call-in show, still contained the Gates Studioette, CB-500 turntables and RCA cart recorder and player.

A new Harris MW-1 AM was placed into service near the end of the decade, moving the RCA to back-up duty and readying the Raytheon for disposal. The MW-1 proved troublesome at first. A bit of icing on the tower frequently knocked the unit off the air. After the station accepted a trial of the new Orban Optimod AM 9000A, my boss fell in love with the sound and bought it.

1980s and the end of an era

A “distressed sale,” forced by the FCC over Equal Employment Opportunity violations, brought Northeast Broadcasting on the scene in 1981. Eventually WHAV AM’s studios moved to the nearby city of Methuen and, by 2002, was renamed WCEC. It still uses a portion of the old transmitter building. The FM was renamed WLYT for a time and today is known as WXRV — The River.

Between 1947 and the early 1980s, and thanks to the relatively frugal first two owners, WHAV’s studio and transmitter buildings continued to convey a vintage look. Almost every piece of equipment ever owned by the stations either remained on air in some fashion or carefully stored in the chief engineer’s workspace. I was pleased to learn the history of the station simply from digging through the relics.

The WHAV call returned in 2004 when I brought it back for an Internet, cable television and low-power (Part 15) radio station. One of WHAV’s first announcers, Phil Christie, and one of its last, Marc Lemay, continue to be heard daily, but that is another story.

Tim Coco worked in the original WHAV studio building between 1978 and 1980. At the time, the building was largely unchanged from its construction 30 years before. He is currently president and general manager of the Internet incarnation of the station.