Get into the Production Groove

Sep 1, 2001 12:00 PM, By Chriss Scherer, editor

The phrase �radio production� is a catch-all phrase used to describe any event that is not created live on the air. This simple description covers several very different areas. The description that comes to mind first is commercial production. This is certainly an important area to consider, since this allows the radio business model to function. But production reaches farther and includes non-commercial production work such as station imaging and promotion, and feature program origination.

For basic voice-overs and simple bubs, a small space can be very efficient for its worload.

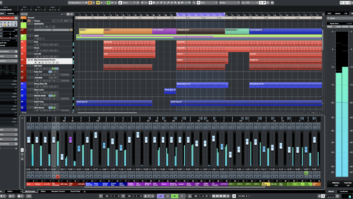

While digital systems have been adopted slowly into the transmission side of radio, the production studio has embraced digital technology and advanced quickly forward with it. It is difficult to witness any kind of editing without the use of a digital editor or digital audio workstation (DAW). The art of cutting tape is nearly lost.

Studio layout

Classically, the production studio has been designed to mimic the on-air studio. The advantage to this idea is that the studio was always available to serve as a back-up air studio. It also made the room easier for the on-air talent to use with minimal training. These are valid design ideas, especially if space is at a premium and the on-air studio requires a great amount of down time for maintenance. With the reliability of most modern equipment, however, this concern is hard to justify.

In most cases, the production studio can be designed to serve its primary function first and fulfill other uses secondarily. If space allows for more than one production studio, each room should be designed to maximize its efficiency for regular use.

With this efficiency of design in mind, the center focus of most production facilities has shifted to the editing system instead of the console. For most short-form radio production � commercial and station imaging � the DAW can likely serve most of the room’s equipment needs. Long-form work, such as feature programs, and extensive mixing may dictate that the console remain at the center of the studio.

Regardless of the studio’s primary function and subsequent layout, in most cases, the studio can still function as a back-up air studio. It may not be the easiest to use for this purpose, but the inconvenience should be easily outweighed by the studio’s greater efficiency and higher quality of work from daily use.

Specialized space

Some production work may require even more specialized space. If a variety of voices are used in your facility, consider a voice-over booth in your plans. This allows the producer to maintain his work space flow without interruption from the additional traffic. A second mic placed in the corner of the room can serve the same purpose, but the producer will need to monitor through headphones, which can cause listening fatigue. Headphone listening also may not provide an accurate listening environment. A separate booth will allow the producer to continue working while the script is read, without worry of additional noise being picked up during the production.

Perhaps a voice booth may not be enough. If interviews are regularly conducted, a larger voice booth or even a full interview booth with several microphones may be needed. This space can also be made available for on-air use by routing the microphones to more than one destination. Automatic mic mixers simplify this routing task and may aid the interviewer who must also record his own interview.

Some production studios have even greater specialized needs. In-house music production may require a full performance studio. Music bed production may require a smaller performance space for a keyboard and drum machine. A club-mix show requires space for a turntable setup. Regardless of the use, the production studio is a creative center, and its design should allow the creative process to flourish without being hindered by the physical space.

Get equipped

The main function of the studio will determine what type of console should be installed. If the DAW will be the main source for all audio and will handle the mixing, then the console needs to be little more that an input level controller to the DAW. A small console with audio selectors or an audio router controller may suffice. If your facility is built around a router/mixing system, the console could be a single fader panel with access to all the facility’s audio sources. If the console is used for the primary mixing, then it will need to have enough inputs to support the number of audio sources used at any time. The use of external processing effects may also dictate a larger console and may require several audio buses or send/return feeds.

The production space should accomodate the work being done and not the other way around.

On-air consoles can be used in production. They may not offer the flexibility that is needed, but they do offer a faster learning curve for most operators. Many broadcast console manufacturers also offer consoles that are designed for production use and include multiple send, return and mix buses in addition to equalization. Live-sound and recording console manufacturers also provide inexpensive alternatives that can be used for radio production. Keep in mind that these consoles typically do not provide console starts or monitor muting like the broadcast versions do. An add-on may be required to provide the desired results.

Digital audio workstations have significantly changed how audio is manipulated. You rarely see anyone splicing tape anymore thanks to these computer-based systems. Ranging from basic stereo editors to full-blown multitrack powerhouses, you can likely find a system that fits your budget and your operator’s skill. The basic systems rely solely on the computer interface for control. Some editors are built around custom hardware to emulate traditional tape machine controls. Still, some systems add hardware interfaces to enhance their function.

To extend the capabilities of DAWs, many systems also support plug-ins. These add features, typically effects processing, to a DAW, eliminating the need for external effects units. There are a few plug-in standards that are used. Most manufacturers support at least one standard if not several. DirectX and VST are two of the more common third-party plug-in formats.

Integration of DAWs with a station’s on-air playback system has been a stumbling block for many facilities. At one time, the only way to transfer audio between these systems was to play the audio file in real time and record it into the other system. The new file then required manual intervention to add the appropriate labeling and traffic information. This is no longer the case, since many DAWS and most automation systems support standards that allow this data to be entered once and remain with the audio file as it is transferred from the system. One unifying system, called the Cart Chunk, was introduced a few years ago. This system has now been recognized by the AES as an established standard.

A little sweetness

While it should be used sparingly, equalization can enhance the final mix. An effective mix will have many layers, and equalization can be used to create sonic space for another source. If a voice track is not cutting through the mix, reduce the level of the frequencies from other sources that are getting in the way. The ability to adjust equalization quickly is preferable to having to open an effects window, make an adjustment, allow the software to process the change and then listen to the result. The same is true for any other effect. Choose the method that works best for you.

If external effects are used, you must determine how you will route these effects into their needed use. As mentioned earlier, if a console is the center of the studio, you may be able to take advantage of sends and returns or additional mix buses. Patch bays, once the staple of any audio facility, are also effective at routing audio. The drawback is the time for installation and ongoing maintenance. Switch banks, like those used for input selectors, also offer a simple way to route effects, but still rely on moving, mechanical connections. Both are available in analog and digital audio versions.

Microphone selection can be a hotly debated issue. Typically, the discussion revolves around choosing a single mic for the entire facility or providing specific mic selections to individual producers. This question can usually be answered by identifying the primary users. If the air staff regularly voices pieces and you want their voices to be recognized, the mic selection should be consistent. A mic processor can allow for some variations, but the difference between a budget mic and a studio condensor is too much to ask.

A mic processor should be set for general use if several people are using it. If the mic is primarily used by one person or the station voice, then adjust the processor for that person. The midday announcer should sound like the midday announcer, while the station image voice should sound like the station image voice.

Some studios may call for specialized equipment for unique purposes. One example is a piano keyboard or a turntable used for live mixes. To an engineer, these are just pieces of equipment. To the performer, these are instruments. Be sure to have input from the final user as to the equipment selection. Keyboard weighting and motor torque have a unique feel. If the performer is not comfortable on the instrument, he will not provide the best possible performance. Some may argue that microphones have a similar importance, but their effect is sonic, not physical. If your facility plan can accommodate everyone on the staff, everyone will be happier, and the quality of production will excel. This can still be the case when the proper compromises are made.

Photos by Andrew Rosenberg and courtesy of Creative Studio Solutions.