For a long time broadcasters have assumed that the digital revolution would take hold in their industry when they, the broadcasters, wanted it to.

Under that assumption, much effort and expense have gone into the planning, standardization and implementation of digital technologies in recent years.

If broadcasters were candid, most would acknowledge that at least part of this strategy was formed with an intent to leverage and extend their legacy positions into the digital environment, maximizing the advantage of the incumbent while minimizing the opportunity for new challengers.

While some would argue that this was improper and manipulative, given broadcasters’ use of the public resource of scarce spectrum, others might counter that it is merely an application of the fundamental human notion of survival writ — or rather, coded — large.

That issue has been largely mooted, however, as it is becoming clear that the digital radio transition may not follow the carefully crafted rules that analog captains have drawn up for it.

As the record industry has learned, the move to digital technology may be revolutionary in the truest sense, with a newly empowered populace dethroning former masters in the process.

Infinite number of monkeys

The mechanisms for this sea change in radio are several.

First, there is the simple issue regarding the volume of new competitors. As we discussed last time, it is only a matter of time before online and on-air radio services reach relative parity in availability.

This vast enlargement of the level part of the playing field will put all radio services into competition on the merit of their content, and not allow over-the-air radio to rest on its laurels of broader access.

Another change engendered by new technologies is what can be called the “Digital Trickle-down Theory.”

It states that as new technologies proliferate, they gradually allow consumers to do more things for themselves that were previously the province of professionals and dedicated service providers.

This principle applies broadly, and has forced those who would remain professionals in their domains to continue to improve their services, in order to remain ahead of the ever-rising consumer DIY curve. Radio is not immune to this phenomenon, as it too is being forced to provide something that consumers can’t do for themselves using new digital systems.

So radio broadcasters are doubly challenged, on both the supply and demand sides of the equation: New media present a glut of suppliers, while new technologies reduce demand for traditional radio services (and lower the perceived value consumers formerly ascribed to them).

There are ways to forestall the direst consequences of this shift, however.

Room at the top

A look at recent history shows that human intelligence still trumps the machine in most cases.

For example, when the first digital drum machine was introduced by Linn Electronics in the early 1980s, there was rampant fear in the music industry that drummers would be put out of business, since now anyone could play the drums with the push of a few buttons on a little console.

In fact, what happened was just the opposite, as generally the only operators who put the device to very good use were drummers themselves, thus gaining a new tool that broadened their palette and value. This pattern has been oft repeated.

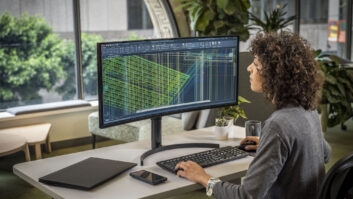

In radio today, the functionality of computer-based automation that broadcasters have used successfully over the last decade or more is now finding its way into consumer media players and “adaptive” online radio services. But can such systems truly match the capabilities of a well-programmed radio station?

Some might say yes (and it’s getting better all the time), while others would say close enough, given the lack of, or substantial reduction in, commercials.

Still others would acknowledge that something is missing, either because of the robotic selections, sequences and segues, or the lack of real continuity (i.e., no DJs, newscasts, time/weather/traffic, etc.).

The key lies in the range of these answers. Trickle-down is just what it implies: down, as in diluted or dumbed down; but it’s a long path. This implies that there is always some room at the top for the most adept professionals to stretch their skills and remain relevant — at least for some portion of the consumer market.

New thinking

Such augmentation of current expertise is just what author and former Al Gore speechwriter Daniel Pink talks about in his celebrated new book, “A Whole New Mind.”

Among many other thought-provoking topics in the work, he considers the impact on American society of what he calls the three As: Abundance, Asia and Automation.

By “Abundance” he refers to the fast and massive consumption habits of Americans, which imply that if you build it, we will come — typically in droves. Successful new stuff is often enormously successful, and relative quickly. And yet the American public is also quite fickle, putting a lot of those new purchases on the shelf fairly soon (but often not getting rid of them entirely; Pink cites the fact that the self-storage industry in the U.S. now grosses more annually than the American movie business).

So differentiating oneself is more important than ever to capture initial consumer interest, followed by even more critical effort toward stimulating the retention of perceived value.

“Asia” is Pink’s label for outsourcing, by which he concludes that if it doesn’t really matter where a product or process is produced, it will increasingly not be done in the United States, since it’s cheaper to do it elsewhere.

Along the same lines, if a process isn’t that difficult to perform (especially if it’s largely repetitive), it can be done by “Automation” instead of human workers.

Pink’s conclusion from all three of these trends is that imaginative thinking — what he calls “right-brain functions” — are required to avoid a negative outcome. If you use creative thinking to develop products, services or value-adds that are difficult to replicate, outsource or automate, you will remain successful in today’s global marketplace.

Thus as consumers and other new professional entrants attempt to supplant the role of traditional radio, those in the radio business need to think creatively to differentiate themselves in new ways, and apply their considerable experience and existing infrastructure to develop well-crafted new services that cannot be easily matched by less skilled operators or automated processes.

This shouldn’t be that hard, but it does require some new and well-focused effort. It could also be fun, particularly for those with a competitive spirit, who find that a challenge drives them to be their best.

Perhaps the hardest part is the need to develop imagination — part of our mental muscle that we may have let get a little soft over the years as the industry has matured. Maybe it’s time to get back to the intellectual gym and train for a comeback.