Listener Research Shows the World Depends on Shortwave for Information, Local Programs

This commentary is an excerpt from the presentation “International Radio Continues to Depend on Shortwave” given by Dr. Graham Mytton, former BBC audience research officer and now consultant to VT Merlin Communications. It was delivered at the CIBAR Annual Conference in London last fall and reprinted and revised for the 2005 National Association of Shortwave Broadcasters conference in Washington this spring.

I am often asked, “Where are shortwave listeners to be found?” or “Is shortwave listening in decline?” or “Are shortwave listeners migrating to FM?” The questions reveal a way of thinking that needs to be challenged.

There is in fact no such thing as a shortwave listener in the way that there is, for example an Internet user, aside from the very small number of dedicated DXer enthusiasts. Many people who use the shortwave bands on their sets every day do not know they are shortwave listeners.

If you ask them if they listen to shortwave they may say “No,” and the same is true if you ask them if they have a shortwave set. They are no more familiar with these technical terms than most people are with, for example, the differences between VHF and UHF TV reception.

Most who use shortwave to listen to radio services they receive are unfamiliar with anything other than the place on the tuning dial where they can find a particular station.

Perceived demise

For about the last 15 years the predictions of the demise of shortwave have been frequent and persistent. It is as if it has been taken as an obvious fact that there would be decline. If the assumption had been made for market reasons, this would perhaps be understandable, although one would hope assumptions were based on real market data.

But we hear reasons given as being to do with technological advance and innovation. In fact changes in technology may not be the main driver with respect to what people choose to do, so far as radio is concerned.

FM is not a new technology. It has been around, even in parts of Africa and Asia, since the 1960s or even 1950s in some places. What is new is a change in the media environment, not the technology. Where there were previously widespread state monopolies in broadcasting, now we see thousands of private services on FM and some on AM in many parts of the world where previously there was only a single radio service provider. But the changes are not principally changes in technology. They are changes in market availability of radio services.

Assumptions have, I believe, been made in this way. Because shortwave is an old technology it must be on the way out. In a world of the Internet and cable and satellite TV, surely shortwave is going to be squeezed out. Or the assumption is made that because shortwave is sometimes unreliable and often noisy, people will choose something clearer and easier to listen to.

This does of course happen, provided that the content available is what they want. But countless surveys will show that people often choose to listen to scratchy and difficult shortwave services in preference to or as additions to locally available services in good quality, provided what is available on shortwave is what they are looking for.

To give just one example, in the dying days of the Abacha dictatorship in Nigeria, when people in Kano had local FM state-owned and -run radio services easily accessible to them, they still listened in huge numbers to the BBC and other broadcasters in Hausa, all on shortwave. This was because they wanted what those services provided which were not being provided locally, no matter what the reception quality was like.

People don’t look for different kinds of Hertz. Nobody listens to HF or shortwave, or for that matter, FM or AM. They listen to radio programs. They look for content. Technical quality always comes second to content.

Unfortunately this message has not been heard, or it has not been listened to, because I have said and written it often enough, as have others. Leading figures in broadcasting that ought to know better have said and done things that have not been based on realities.

For example, Richard Sambrook, now director of the BBC’s Global News, and therefore in charge of the World Service, speaking when in a senior position in BBC News eight years ago at a conference in London, spoke of the “migration away from shortwave.”

When I pointed out to him that there was no such migration, he expressed astonishment. He admitted that he had said this not on the basis of any evidence, but just that he assumed it was true. There have been too many assumptions like this.

The previous director of Deutsche Welle once spoke on similar lines when talking about the policy they had adopted of reducing shortwave services to, for example, Turkey. In fact, as research at the time showed, the only station to lose audiences over the period he was talking about was Deutsche Welle. I was convinced at that time that DW had lost listeners because it had cut back its availability on shortwave.

And I don’t need to go over the painful experience of Radio Canada International in much detail. Between 1990 and 2000 it was subject to almost continual cuts and threats of cuts. Their audience declined sharply. Some used this fact to argue that listening to the station was in decline and that the cuts were an acknowledgement of that.

In fact, decline was almost certainly mainly the result of the cuts. Here and elsewhere we have seen the enactment of self-fulfilling prophecies.

The investment in shortwave

There is something very odd and rather ironic about the assumptions that have been made about shortwave. They came at the end of a period of massive investment in shortwave enhancement and improvement. In the BBC we had what we called the “Audibility Programme” that stretched from the early 1980s through into the early 1990s.

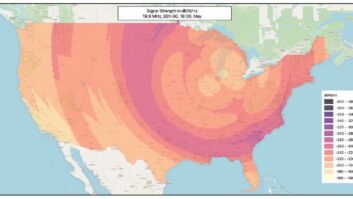

Not only were all existing shortwave facilities greatly improved and strengthened, at Singapore, Cyprus, Oman and Ascension, as well as in the U.K. at Rampisham, Wooferton and Skelton, but also new sites were opened in Hong Kong (later moved to Thailand), the Seychelles and most recently, Oman.

Shortwave became very good. Most major target areas were reachable by a first-hop service and with higher signal strengths than ever before and with much more efficient aerial arrays. And it was not only the BBC that made such improvements. RFI launched a huge investment program focusing on improvements at its main transmitter site in Issoudun.

VOA opened several new transmitter sites in Botswana, Sao Tomé, Morocco and elsewhere. Deutsche Welle also made several new investments in Germany and, despite many difficulties, in Sri Lanka.

The results of many of these investments in new, more powerful and better focused shortwave could be seen in larger audience reach in several parts of the world, most notably in Africa where audiences for all major international broadcasters grew impressively during the 1990s. The investment in shortwave has been vindicated and justified. It was a period of huge success, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Why then was there this extraordinary about-face in the policies of the major broadcasters? Was it simply because local FM relays and rebroadcasts became possible as a result of changes in the regulatory environment in several countries, and in order to fund these, cuts had to be made elsewhere?

This was certainly the case at times, because I was present at some of the discussions in the BBC. But I always made it clear that FM could never be a replacement for shortwave, unless the local situation had changed so much that people in the entire target area had enough local choice and therefore no longer had any need to tune to shortwave. This is the case in Europe and parts of the former communist world. But the same cannot be said of Africa, or much of Asia.

I endorsed and supported the decision to stop broadcasting services in Portuguese and Finnish to Europe. It was also sensible to stop shortwave broadcasts in Polish, Czech, Greek and a few others. Indeed, I suggested that the need for these services to be continued at all was at least questionable. The BBC stopped broadcasting in Swedish, Norwegian, Dutch, Italian and Japanese. Perhaps other languages should also be closed in favor of new services in new languages to people in greater need.

FM is no alternative

FM, by its very nature, cannot be a simple replacement for shortwave. Its reach is very limited.

I have just been in East Timor, where both Radio Australia and RDP Portugal have a local FM relay in the capital Dili. Neither can be heard far outside the town, and not only because of the power of the transmitters. Dili is hemmed in by hills.

Beyond these, you have to use shortwave to get either service. And to listen to the BBC or VOA or any other international broadcaster, East Timorese have to use shortwave wherever they are. And they do!

That is the first weakness of FM. Its reach is very limited, especially in hilly countries. There are five other serious weaknesses.

The second is that it is subject to local regulation and approval and both are at risk at any time. And they are at risk from the very factors that make the ability to listen to alternative voices important. The BBC and other broadcasters have had several problems with this; services have been opened then closed or restricted in both Congos, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, several former communist states and no doubt others. And this draws our attention to a grave risk inherent in over-dependence on FM.

When FM services are cut because of a change in government or a change in the political atmosphere and resort has to be made to shortwave, how does the audience know where to find you? Has an adequate shortwave service been maintained, and more importantly, has it been fully publicized?

Even when restrictions are not imposed for political reasons when the government wants to restrict the flow of alternative news, it may be that the demands of the BBC, VOA, Deutsche Welle, RFI etc. have to take second place to the competing demands of potential commercial and other local broadcasters.

The BBC is not on FM in more than a very small handful of European cities. This is not because of political restrictions but because the demands of local broadcasters tend, understandably, to take precedence. The BBC boasts of its FM coverage in many parts of the world. In fact it is very thinly spread.

Now for the third weakness: FM is often unreliable. Breakdowns are common, as are problems with modulation and related technical difficulties. This is not because the medium is inherently faulty but because of weaknesses in local support services. The transmitters are not always properly or fully maintained.

Shortwave is more reliable and, by the way, it is often as good as FM in terms of its received quality. My wife and I were on holiday not long ago at a beach hotel just north of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. The BBC is available locally on FM. It is also available on shortwave from Seychelles. The quality of both is equally good. In several blindfold tests my wife was unable to tell which was which. The shortwave was there every day. The FM was not.

If I lived in Dar es Salaam, as I did several years ago, I think I would always use shortwave. It is always there, always excellent and it provides a continuous service without breaks.

Moreover, and this is the fourth weakness: We could choose ourselves whether to listen to the Swahili or the English. Listening on FM, the decision was not mine to take. FM relays often switch between languages. Some carry the BBC, VOA, DW, RFI, etc. only for certain periods.

The fifth weakness is a connected one, and it is the fact that many relays and rebroadcasts are out of the control of the originator. Program or services from the BBC, VOA, DW or RFE, etc. are carried by an independent broadcaster, at times chosen by that broadcaster. The listener cannot tune to the BBC, VOA, DW, RFI etc. as a distinct station when he or she chooses.

The relationship of the broadcaster to the audience is completely different. There is no longer that close relationship whereby the listener is choosing the station that he or she wants to hear.

The sixth and final weakness of the FM strategy is its greatest shortcoming. It is never available where it is most needed and by those for whom shortwave is literally a lifeline. Let us just think of Dhafur at present. There will be many caught up in that tragedy who have radio sets. If they are listening to anything at all, it will be on shortwave. There is nothing else available.

I mentioned East Timor earlier. I talked to people there about what had happened during the crisis of 1999 when they voted for independence from Indonesia in the referendum and the Indonesian militia trashed 90 percent of the buildings in Dili and elsewhere. People fled into the hills and they listened to the BBC, the VOA, Radio Australia and others on shortwave. Several people told me there is still an audience for these stations on shortwave throughout the country.

Let it be noted at this point that East Timor has never been surveyed. It is as if these listeners do not exist.

Bedrock of international service

Shortwave remains the main way in which most people continue to listen to international radio broadcasting. It will remain the case unless the major broadcasters continue their false assumptions about its decline, and make that decline come true by their actions.

I believe the research being done is not sufficiently reflecting the realities of international radio listening. I believe the obsession with performance in relatively easy to measure radio markets is blinding strategists to the wider realities in those many areas where research is difficult or where the societies involved are being seen as marginal or not a top priority – many of the most vulnerable and needy people in the world, who the international broadcasters have mostly served very well in the past.

And I believe a misguided obsession with the supposed rise of new technology has created an atmosphere in which the reality is ignored or understated.

John Tusa, director of the BBC World Service from 1986 to 1992, said during his tenure at Bush House that if the technology of shortwave were to have been invented or discovered today, people would be amazed by what it could do.

It can reach anywhere from anywhere, without the need for phone lines, local permission, local regulation, expensive equipment or subscriptions. But it is old, it was invented and its properties discovered by Marconi 100 years ago. Therefore surely it must be past its “sell by date.”

This is utter nonsense as we all know, but it is time for the big broadcasters to wake up before it is too late and they find that their listeners have deserted them, not because they don’t want the product, but because they can no longer reliably find it.

I have amazed myself by not mentioning DRM (Digital Radio Mondiale) until now. So I shall do so in closing.

DRM has all the advantages of shortwave with none of the disadvantages. It is an essential facility for the future. But it will succeed only slowly, possibly very slowly. Those in the world who most need the services of international broadcasters are most likely to be the very last people to have DRM sets. Just as they are likely to be the last people to have the Internet, satellite reception, FM services and all the other much trumpeted new technologies that are said to be transforming our world.

Analog shortwave will remain for a long time to come the bedrock of international radio service delivery. That remains true, unless the major broadcasters are foolish enough to ignore the facts of international radio audiences that I have outlined here.

RW welcomes other points of view.