SALEM, Ore. — The Oregon Office of Emergency Management has accepted a credentialing plan that will be used to qualify broadcast technical staff to participate in the state’s “first informer” access program.

It is not the first such program, but creators of the training criteria also believe their formal training approach will encourage similar initiatives for broadcasters in other states.

First informer measures allow designated broadcast engineers to enter areas during emergencies to maintain essential equipment. Oregon adopted a law in 2015 and tasked the Oregon Association of Broadcasters and the state’s Office of Emergency Management to develop a procedure to credential participants. Local chapters of the Society of Broadcast Engineers were enlisted to participate.

Engineers designated as first informers in the Beaver State will be allowed to cross police barricades and travel roads within emergency areas to maintain broadcast facilities — most often transmitter sites — with needed fuel, food, water and equipment.

Oregon joins Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Virginia with “first informer” laws in place, according to the National Association of Broadcasters. At least nine other states including California, Wisconsin and Florida have related plans or agreements with state governmental agencies, NAB said.

The first informer concept has spread since Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005 and Super Storm Sandy pounded the northeast United States in 2012.

Oregon named its first informer card the “broadcast engineer credential” because it will only be made available to broadcast technical staff, planners said.

CREDENTIAL

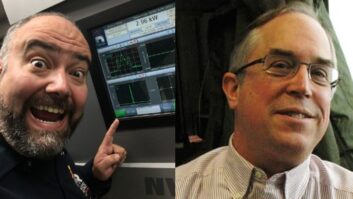

“This agreement in principal is critical to the structure of the credentialing program and ultimately will help keep broadcast stations operating during an emergency and keep the public informed. It will be open to broadcast engineers and those with related functions,” said John White, chief engineer of KKPZ(AM) in Portland and chair of the credential planning committee.

“Many broadcast engineers have a deep commitment to public service, and we see that as a crucial part of the commitment.”

The initiative will be administered by a Broadcast Engineer Credentials Committee, consisting of broadcasters, broadcast engineers and representatives of the Oregon Association of Broadcasters. SBE chapters will help administer the program and coordinate training required for those who participate.

A sample training list provided by the credentialing program’s creators shows initial qualification requirements of approximately nine hours of instruction. “Introduction to Incident Command System” is a Federal Emergency Management Agency training module that takes approximately three hours to complete. FEMA’s “ICS for Single Resources and Initial Action Incidents” is another training requirement, as is FEMA’s “National Incident Management System” online class.

“The training, which is all free and available online, is meant to familiarize broadcast engineers with the workings of emergency management,” White said. The initial training could be completed in “two to three weeks” with an aggressive timeline, White said. Participants also will need to report ongoing emergency and safety training twice annually.

The SBE will oversee the qualification verification, approval and card production tasks of the program, White said. The society “will be the feet on the ground helping to make this happen. SBE does an excellent job of broadcast engineer certification at the national level. We hope to implement our Oregon broadcast engineer credentialing program at the three local SBE chapters in the state,” he said.

The program is open to registered professional engineers practicing in the broadcast field, broadcast service providers such as consulting engineers and individuals designated as FCC chief operators by local stations, White said. Officials believe as many as 200 people in the state could apply.

“Eligibility will be available to SBE members, though there is no requirement to join SBE to become credentialed,” White said. “I do expect the majority of the engineers that apply will apply as a SBE certified engineer.”

White credited local SBE chapters in the state with providing input from field engineers during the planning process.

“Some of our qualified training items are also applicable to SBE continuing education requirements,” White said. “For instance, an IPAWS training module will be applicable to both ongoing SBE certification and ongoing first informer credential training.

The success of the program in Oregon will rely on building relationships between broadcast engineers and the local emergency managers, White said.

“That is what makes our program unique. We have been able to develop a partnership with emergency management here in Oregon at the state and local level. Our credential card will actually carry the state logo and the authority of the state. The committee will be able to thoroughly vet candidates and to pull the credential if there is misbehavior or for any reason,” White said.

NOT FOR REPORTERS

James Boyd, president of Boyd Broadcast Technical Services and a member of the Oregon Association of Broadcasters, said law enforcement had expressed concern that media members could cross the yellow tape into secure areas.

“There was some pushback from police and firefighters. The big concern was that this law would let loose a whole bunch of reporters into areas blocked off during emergencies. This is not for reporters,” Boyd said. “And Oregon will require participants to abide by a code of conduct.”

Boyd expects a number of broadcast engineers “to aggressively pursue” the first informer credential when training becomes available later this year.

“I could even see our credentialed people eventually doing some cross-training with local emergency managers,” Boyd said.

Applicants will be asked to pay a small fee to help cover the credentialing process, Boyd said. “Broadcast first informers will also be required to maintain some minimum personal protection equipment, including a hard hat, lime green safety vest, first aid kit, fire extinguisher, metal whistle, chemical goggles and dust mask.”

In addition, tool recommendations include a “D” size flashlight, pry bar and multitool kit, according to the credential planning committee.

Boyd said the program will demand time of broadcast engineers from across the state to step up and support the program as volunteers.

“We face the real possibility of a 9-plus earthquake [in Oregon]. The potential is there for such a catastrophe. Having a large number of broadcast engineers as first informer will be critical to maintaining as much communication infrastructure as possible and recovering from such an emergency,” Boyd said.

OREGON SHAKES

If earthquake experts are correct, officials in Oregon and neighboring states have reason to launch programs aimed at keeping critical communications infrastructure operating.

In fact, a major quake is overdue in the Pacific Northwest United States. Seismologists warn of a “big one” striking along the Cascadia fault, which sits at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean just off the coast.

Emergency planners held a large-scale preparedness exercise in June called Cascadia Rising to simulate a 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake and tsunami along the Washington and Oregon coast. Ken Murphy, a regional administrator for FEMA, said at the time that “A 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake will be a disaster unlike anyone has ever seen.”

Such an earthquake would collapse hundreds of bridges, wreck many coastal highways and cause considerable damage to urban areas, experts say. A resulting tsunami could flood coastal sections of Oregon.

James Boyd, one of the planners behind Oregon’s first informer credential program, said such warnings add a sense of urgency to planning for a disaster.

“The experts say that earthquake could happen any day. This part of the country is very aware of the threat. That’s what really drove this whole effort.”

White and Boyd believe the criteria developed for the first informer program are unique due to the level of involvement by SBE.

“We are certainly willing to share what we have done here with other states. This has really been a cooperative effort between broadcasters, the emergency management community and SBE,” White said.

The society’s national leadership is aware of the Oregon training initiatives involving local chapters and said they would welcome the opportunity to help other states.

“The SBE is supportive of the efforts being made in many states to establish ‘first informer’ access to broadcast facilities in time of emergency,” said Jerry Massey, CPBE, 8-VSB, AMD, DRB, CBNT, president of the society. “The broadcaster associations in these states have worked closely with their states’ SBE chapters and we will continue to support our members’ and chapters’ involvement as other states look to create their own versions of a first informer access law.”

Massey said the SBE could consider developing a specific SBE first informer certification, which would have to undergo the review of its Certification Committee.

“The decision would be based on whether it would help the cause of first informers and if it would benefit our members,” Massey said.

Oregon state officials expect to hold an official signing ceremony in October to signify the launch of the program in the state. White and others plan to make presentations to educate engineers on the important of completing the credentialing process.