National Public Radio’s Public Radio Satellite System is getting good feedback from station engineers and content producers for its audio level survey.

NPR Director of Technology Strategy Chris Nelson tells me the survey, which has been in the field just a little more than a week now, will remain viable for a total of three weeks. At the end of the summer, results will be compiled and NPR, along with American Public Media, will make recommendations to the Distribution/Interconnection Committee, a subgroup of the NPR board that oversees the PRSS.

The varying levels of audio content distributed to stations has long been an issue. We reported last year that John Kean of NPR Labs studied the issue, which was also discussed at the Public Radio Engineering Conference in April. The PRSS is tackling the issue now because it believes “the technology that measures and manages audio loudness has matured to a point where we can introduce it to the public radio community,” according to Nelson.

Nelson tells me he and Alice Goldfarb of NPR Labs looked at some 6,000 audio files to get a sense of the problem. They found audio levels that were “drastically different” from source to source, according to Nelson, including a 20 to 25 dB difference between some programs within PRSS.

The goal of the recently issued PRSS survey is to gather information so that PRSS can improve the consistency of the audio it distributes. NPR and APM together have been discussing the audio level inconsistency issue with content creators and distributors.

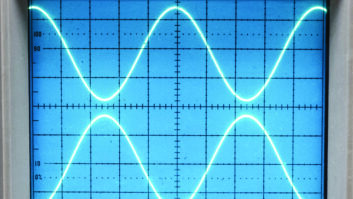

The industry is moving away from digital peak meters to measure sound and towards newer loudness meters that give a numerical reading of the perceived volume of audio content. NPR added loudness meters to its in-house broadcast studios in April.

The broadcaster noted that before the switch its audio engineers had been interpreting the older digital peak meters in different ways. Before, “Some may have driven a show 3 to 6 dB louder than others.”

Now that NPR’s engineers are using loudness meters Nelson has seen improved level consistency across shows like “All Things Considered” and “Morning Edition.” The newer meters, which measure in loudness units, display an easy-to-read numeric value instead of a rapidly moving meter. “Interpreting meters is no longer subjective,” he tells me.

Television broadcasters use similar loudness measurement tools to control level differences between programs and commercials. The Advanced Television Systems Committee developed a loudness standard for television stations to comply with the Federal Commercial Advertisement Loudness Mitigation, or CALM Act. The ITU, EBU and AES also have loudness recommendations for broadcasters.