Third in a series of blog posts exploring recommendations of the new National Recording Preservation Plan of the Library of Congress, which touches not only on radio but on audio in general and its place in our cultural history.

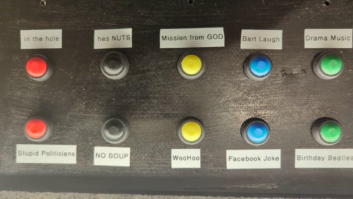

Do you still have those ancient cart machines, or old manuals for DAT machines, stacked in the hallway closet? Soon you might be asked to register them.

The library’s plan — in addition to urging the preservation of American commercial radio programming and more research into ways to preserve audio recording media — also explores documentation of legacy technologies.

“There must be a systematic and sustained effort to compile and collect information related to legacy recording technology and practices: where it is, how it works and the characteristics, or ‘audio signatures,’ of the recordings themselves,” the authors wrote.

“Additional efforts should be made to thoroughly document the expertise of legacy recording practitioners. This work can serve as the cornerstone for the development of standardized methods and best practices for audio preservation reformatting, and will be shared through the Audio Preservation Resource Directory [another plan recommendation] to serve the needs of training and education.”

Specifically, the library’s plan calls for:

— A national directory of available obsolete equipment as a resource for audio preservation and restoration engineers. This would tell where experts could locate the gear needed for playback and transfer of legacy recording formats.

“The directory should inventory obsolete or difficult-to-locate equipment in the offices or studios of various record companies, independent studios and independent producers,” it states. “It should list tape machines, recording consoles and outboard gear (e.g., equalizers, reverb units), among others, because such elements may be sought by those attempting to restore or reissue historical recordings.” (The authors didn’t list cart machines at radio stations here; but given that preserving old radio content is one of the plan’s explicit goals, their inclusion seems likely, along with any other audio recording formats ever used in radio … DCC, anyone? anyone? … Bueller…?)

“For each audio facility, the directory should list contact information and the financial and logistical terms on which access to the gear can be obtained.”

This compilation, they envision, could be a joint project of the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, Association of Moving Image Archivists, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, and AES. This directory could grow later to include an appendix “with a year-by-year or decade-by-decade list of major formats used at different stages of the recording process, including recording, mixing and mastering.”

— A program to videotape interviews and demos by senior audio engineers.

“To document recording practices used to capture sound from legacy media, lecture demonstrations by expert practitioners should be videotaped. They should cover older formats, playback techniques and playback systems.” These would be developed by the library’s preservation board and made available on the proposed Audio Preservation Resource Directory as podcasts or webcasts. I suspect this would be popular content not just for preservationists but for audio history enthusiasts.

— A digital repository of manuals and schematics for legacy equipment.

“A coordinated effort is needed to systematically acquire service manuals and schematics for all legacy playback equipment. It is necessary to identify gaps in the collection, solicit donations of manuals and request the support of manufacturers and interested archives and libraries.” The library’s Packard Campus has begun this process.

Coming up: Problems that digital media present to preservationists.