Stuart Holland Radio reading services, which often operate on the FM subcarriers of public radio stations, are facing tighter budgets and shrinking staff. That has led some audio information services to make cuts or discontinue operations.

Reading services, also referred to as audio information services, provide spoken word audio programming — books, magazines, newspapers — for visually impaired audiences, who typically receive programming on specialized SCA receivers via FM subcarrier channels. The audio programming also is often available via public television stations and cable TV systems.

Services have expanded their platforms by introducing podcasting, streaming and cellphone apps to their mix of over-the-air and dial-in services, observers said.

The number of services has gone down since the early 1990s, according to several sources, including the International Association of Audio Information Services, advocacy and education group. In 1992 there were 125 services in the U.S. as compared to 108 today, according to IAAIS data, while a search for radio reading services on the American Federation for the Blind website lists 103.

Most RRSs still have a relationship with their local public radio stations, paying for an SCA or bandwidth for a nominal fee, or else having that donated. (The FCC said it doesn’t have data on the number of audio information services operating on FM subcarriers.)

Financial support for the non-profit services typically comes from listener contributions, state and municipal funding, endowments, grants, corporate gifts, community service organizations and fund-raising events, according to the IAAIS.

Notable radio reading services in Florida, Oregon and Utah have cut services or shut down in recent years. The most recent to do so, Reading and Radio Resource in Dallas, Texas, ceased operations in late 2014, citing financial pressures and new technologies that have replaced the need for the service.

Some supporters of audio information services believe demand for their services is going up as the baby boom generation ages. However, others claim the Internet and other technologies can improve audio quality and provide more options for the visually impaired to receive helpful services.

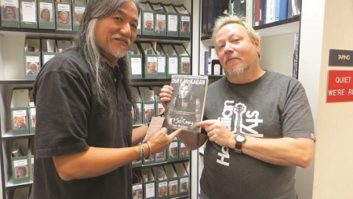

Radio World asked IAAIS President Stuart Holland about the hardships of radio reading services and what his organization is doing to help. He is also manager of the Minnesota Radio Talking Book Network and has been an IAAIS board member since 2001.

RW: What is the job of IAAIS in 2015?

Holland: The IAAIS is the umbrella organization for audio information services around the world. We exist to share information with each other about technology, trends, best business practices and advocate for agencies with governments for funding and support.

FROM THE PAGE TO THE EAR

Audio information services began by being called radio reading services because using space on a FM subcarrier channel of a public radio station was the only broadcast option at the time, according to Stuart Holland, president of the IAAIS.

The first such service, Minnesota Radio Talking Book, was launched in 1969, the brainchild of Minnesota Public Radio’s Bill Kling and State Services for the Blind Director C. Stanley Potter.

That service set a trend around the U.S. In some areas where radio signals were not as dependable as television signals, a similar arrangement was made with public TV stations; the audio was carried on the TV’s second audio programming or SAP channel, Holland said.

In 1976, copyright exemption was clarified by the U.S. Congress (Public Law 94-553) allowing reading services to broadcast material to those “who are unable to read normal printed material as a result of their handicap” as long as the access was not also made available to the general public. Since the stations were on subcarriers, the rules of the FCC were not enforced, Holland said.

The group said an estimated 20 million Americans are living with a significant vision loss and suffer from print disability.

For a couple of reasons, most of the member services are in the United States. First, the concept of audio information services for people who are blind or with visual disabilities began in the U.S.; and second, the U.S. is covered by a patchwork of services in most major population areas. Most other countries with audio information services have a more coordinated national system. In Canada, for instance, the government-run service AMI, which is a member service of the IAAIS, is carried on a national cable network. The number of member services varies slightly from year to year, losing a few, gaining a few, but remains around 85 member services.

RW: What trends are affecting your membership?

Holland: There are two major threats to audio information services: funding and technology.

The funding problem is obvious; since the U.S. is covered with a patchwork of services, each service is funded in slightly different ways. Some depend on government funds, some on local donations and some on grants — but in each case, the stations need to convince funders that the service is worth funding.

And that ties into the technology challenge. We have more and more access to information with some amazing technology, and much of that is actually accessible to blind people. So many funders believe that the access to technology counters the need for our audio information services. It does not.

First, we do not only serve the blind and visually impaired communities. We serve anyone who cannot read the printed page — for any physical reason. That includes people with brain trauma, MS, dyslexia, quadriplegia and more. Plus, blindness in the west is usually an age-related issue.

Though the numbers of elders who are using new technology are increasing, there are still huge numbers of older people who will never use a computer or cellphone. The technology that some people tout as the solution to access is still unavailable to many. Plus, one of the advantages of having a local audio information service is that it can truly be local; people can have access to what is happening in their own communities, not just what would appear in national news publications. Not all the information in local publications is available in a digital format.

RW: Tell me more about the newer technology.

Holland: Technology is a great benefit to our services. When our service industry began, we recorded magazines and books on reel-to-reel tape, and broadcast on analog “side-channel” radios. That was our only option. The result was information with occasional crosstalk, fuzzy signals in places and frustration. New technology has allowed our signals to be broadcast on digital radios, Internet streams and archives, cable television, phone apps, podcasts and more. So we are really at a crossroads with technology. We need to continue the service in a format that works for people who do not, or cannot, use modern technology. But we also need to be expanding our options for those who do use and depend on the technology now available.

Members of the IAAIS board include Amy Hatter and Lori Kesinger (seated) and, from left, Mark DeWitt, Jane Carlson, Melanie Brunson, Stuart Holland, Andrea Pasquale, Marjorie Williams, Brad Walker, Mary Frances Evans, Neely Oplinger and Jennifer Nigro.RW: Why are RRS budgets so tight? Are public broadcasters spending that money elsewhere?

Holland: Not all money for operation of audio information services comes from public radio stations, though they are required to provide audio space for reading services on their signal if asked.

I think there is a myth that public radio and television stations are all run in the same way and walk in lockstep. There are connections, but each station makes its own decisions regarding how much national feed to use, whether or not to broadcast in HD, how to divide up the signal and what to use on it. And not all audio information services are carried on public radio. As I indicated above, some are on cable television, some are on college radio stations and a few are actually on mainstream radio channels.

RW: What kind of outreach or education does IAAIS offer to assist members to help with fundraising issues?

Holland: This last year, the IAAIS became more active in advocacy for their member stations that we have been in recent memory.

The IAAIS hosts national conferences at which there are always workshops on fundraising. But we also offer mentoring and our list server where member services can ask for advice from other stations. We also have a program in which member services can share items that they have recorded, making them available to any other service; and I know that there are materials there regarding fundraising.

But as an umbrella organization, we cannot do the work for individual member services. We can instruct and advise. We can advocate for them with funders. Ultimately, each service needs to do the work necessary to provide the money for their service.

RW: How is IAAIS dealing with challenges brought on by how pubcasters use their analog subcarriers?

Holland: Individual member services need to find their own solutions to the changes happening in technology. Public radio stations are shifting more and more to digital broadcasting, though there are still holdouts. There are still member services that use analog radios. The IAAIS cannot dictate to any member what they need to do. However, we continue to educate our member services through our conferences, information that we share on our list server, webcasts and mentoring.

RW: Do many pubcasters devote valuable HD Radio multicast channels for RRS programming?

Holland: When HD Radio hit the scene, there was a great deal of excitement about it. The IAAIS devoted a lot of energy and time to the issue and co-sponsored the development of an accessible HD Radio so that IAAIS member stations could get out of the business of supplying radios to our subscribers.

HD Radio did not take off among the general public or, as I understand it, with as many public radio stations as much as expected. Most IAAIS member stations have not added HD Radio to their distribution methods, though there are a few around the country that have. I think many public radio stations would actually be very willing to find room on their HD stream if asked, but most have not been asked. There is no groundswell demand for it.

RW: How many audio information services are currently streaming their broadcasts? Is Internet delivery of RRS programming the future?

Holland: I wish I knew what the future really holds. I don’t have statistics, but I believe the percentage of stations that stream is probably around half, and increasing. What we realize is that we need to continue looking at additional ways that we can get our information distributed because people are accessing information in newer ways every day. We are looking at an IAAIS app for phones.

But as I said earlier, we cannot forget the people who cannot access the technology for various reasons other than just blindness. The simplest technology is sometimes the best — we will always need to have some form of access that a person with severe disabilities can turn on with a button or lever.

RW: Technology has made reading services available on many platforms. Which technologies are growing the fastest, and could they eventually eclipse the need traditional subcarrier broadcasts?

Holland: Member services are excited about the potential that Internet streaming brings. By simply providing a stream and hooking up with a few apps, an RRS can be on several different devices at the same time. One of our members counts 28 different ways they are delivering their broadcast. I think that the exciting shift in the industry is a move away from worrying about how a listener is consuming the content and a greater emphasis on the quality and diversity of what they are consuming. It will be a long time before RRSs will completely move away from SCA broadcasts, but our member services are working hard to be on the devices our listeners are using.

RW: What is the “silver tsunami” that some RRS professionals describe? Is demand for their services growing?

Holland: The “silver tsunami” refers to the fact that baby boomers are reaching that age when they will no longer be the working population. In the west, the majority of eye conditions happen to older people — macular degeneration and retinopathy. The assumption is that more and more cases of blindness and limited vision will occur.