TOWSON, Md. NPR Labs successfully demonstrated captioned radio using over-the-air IBOC signals of several stations as part of its Election Night coverage.

If all goes according to plan, the network hopes to generate captions for its main programs by the end of 2009.

Steve Gregory lost his hearing late in life; he drove from New Jersey to see the demo in Maryland. Photos by Leslie Stimson Deaf and hard-of-hearing people who have experienced the captioning are excited about it, saying it will help them use and enjoy radio — again, or for the first time.

NPR Labs personnel plan to meet with receiver makers in January before the start of the Consumer Electronics Show, hoping to encourage one or more manufacturers to produce HD Radios that can receive and decode the captioning.

The International Association of Audio Information Services has developed design standards for captioned radios to help manufacturers.

The idea is to build in accessible features from product inception, rather than trying to include a feature when a product is farther along the production path and “reasonable accommodation” becomes an unreasonable expense, according to Dave Noble, chairman of the IAAIS HD Radio Task Force and development director of radio reading service Sun Sounds of Arizona.

Observers believe designing accessible features into a radio design platform early is key, particularly given the state of the economy.

Nearly 7 million people in the United States are deaf or hard of hearing, according to Gallaudet University; many more have trouble with their hearing.

“We think accessible radio makes both economic sense and social sense,” said Dr. Ellyn Sheffield, assistant psychology professor at Towson University. She is co-director of International Center for Accessible Radio Technology, located at Towson, along with Mike Starling, NPR VP/CTO and executive director of NPR Labs.

WGBH in Boston sent captioned text from a CNN audio feed to NPR on this iBiquity Digital reference receiver. Public radio stations in Arizona, Baltimore, Boston and Denver used similar receivers on Election Night. “We’re looking at some 650 million people affected by sensory issues such as low vision, blindness, hard-of-hearing and deafness,” she said.

Funding

Digital radio offers an opportunity to reach these groups of consumers with emergency information and reading services as well as captioning, Sheffield said.

The captioned radio project is a joint effort of NPR, Harris Broadcast and Towson University; Harris has contributed $50,000 in funds over two years as well as engineering support. But more money is needed and several things have to happen at the same time in order for captioning and radios to be available in 2009.

The network is trying to cut the expense of live captioning, which typically can cost around $120 per hour, according to Starling.

IBM is working on a speech-to-text algorithm that promises to deliver live, real-time translation, rather than a typical delay of 20 minutes or more. That algorithm is due to be ready in 2009, Starling said.

With such an algorithm — combined with the efforts of, say, an English student paid $20 per hour to clean up any garbles — live captioning becomes more cost-effective “and would help the network make the commitment” that it will caption its main programs next year, he said.

NPR seeks to obtain an underwriting commitment towards the cost of generating captions; its estimated cost could be roughly half a million dollars per year — 100 hours of live programs per week multiplied by $100/hour of bargain bulk caption pricing multiplied by 52 weeks, for a total of $520,000.

HD Radio receivers capable of displaying the captions would be needed. The technology uses IBOC’s data capacity to carry text data to be shown live on a screen on future versions of HD Radio receivers.

Participants watch the captioning on screens at Towson University. At least four receiver manufacturers have expressed an interest in making HD Radios capable of decoding and displaying the captions but none has made a formal commitment. Radio World has reported that Radiosophy and Delphi are among those interested.

Ibiquity Digital Corp. would need to incorporate the specification for live captioning in its chipsets next year and then work with receiver manufacturers on the displays. It has committed to following through on these actions, Starling said.

Participants

In an exclusive demo a few days before the election, Radio World staff saw captioned text of CNN programming coming off a Web feed from WGBH in Boston to NPR and displayed on an iBiquity Digital reference receiver — the same type of unit that was then used on Election Night at public radio stations in Arizona, Baltimore, Boston and Denver.

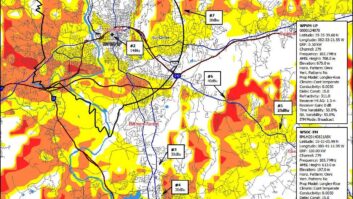

The captioned election broadcast was shown at listening demos on Nov. 4 at NPR in Washington and at FM stations KJZZ, Phoenix; KCFR, Denver; WTMD, Towson, just outside Baltimore; and WGBH, Boston. The stations carried the captioned text as part of their HD Radio signals.

A total of about 100 deaf or hard-of-hearing participants came to the events by invitation, according to NPR. About 100 people also took the online survey.

NPR publicized the listening events and online survey and contacted organizations that work with deaf and hard-of-hearing people in the five locations; it expected more people to take part online.

Election Night was a busy time, depressing online participation, observers speculated.

The election demo at NPR used WAMU’s HD Radio transmission of the captioned coverage. NPR also carried the captioned broadcast and a survey online at www.npr.org. Harris linked to the broadcast and survey from its Web site.

At the events, participants saw scrolling text projected onto large display screens. The image was fed by an HD Radio reference receiver that can decode captioned text included in the data portion of the IBOC transmission. The reference receiver was hooked up to a computer and monitor.

The demo chain

To create the caption displays at the demonstrations, NPR in Washington first sent audio of the election programming via a phone line to WGBH, where stenographers quickly transcribed the material using headphones and special keyboards.

WGBH sent a text stream back to NPR on a socket connection so that NPR could uplink the feed to participating stations via the Public Radio Satellite System on a dedicated data channel.

At each participating demo location, the text stream then was fed to a defined port in a station satellite receiver, which, in turn, fed into the station’s HD Radio importer in its main air chain. Demo attendees saw text that was airing over a radio station’s signal.

Several of the deaf and hard-of-hearing participants at the Towson event had traveled through several states to see the demo and said they eagerly have been anticipating captioned radio. Such capability would make radio easier to use; they also said the emergency alert component of the project is vital.

For example, an HD Radio could carry an alert caption or, someday, trigger a strobe light or a bed shaker in the event of an emergency, a function that’s part of the accessible feature set ICART is developing.

Captioned radio would help Amanda Comninos use radio more, especially in the car. The 22-year-old Towson University senior doesn’t use radio much now; she finds it’s easier to get her news from TV and the Internet. She has some hearing and uses her iPod to listen to music.

Christopher Watters, from the Baltimore area, told RW captioned radio “would help me follow what’s going on in the world,” and “for emergencies. There’d be a lot of benefits.”

Emergency alerting

Deaf and hard-of-hearing people can’t benefit from traffic reports on the car radio, Watters said, and may be unaware of alternate routes around an accident. Captioned radio “would limit my dependence on other people.”

Lisa Kornberg, director of the Maryland Governor’s Office of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, used to listen to listen to radio before she lost her hearing over time. She’s “thrilled” at the prospect of captioning and wondered if other radio companies besides NPR eventually would offer it.

The emergency alerting aspect appealed to her and likes that captioned HD Radios could have a battery backup. Such a radio could have helped her and her friends as they drove to Florida as Hurricane Andrew approached in 1995. They noticed they were the only ones driving toward the coast on I-95; everyone else was driving the other way. Kornberg stopped at a gas station and asked the attendant to call her father, who was able to tell her about the approaching hurricane and to leave the area.

In Arizona, Ralph Hogan, DOE at KJZZ(FM), in Tempe, said his station was the first to get its demo operational since some participants came early; several took part in the surveys, including the president of the Arizona Association of the Deaf, Jim Oster. Many attendees are “eager to continue participating in the dialogue” and interested in hosting workshops with member organizations that serve the deaf and hard-of-hearing, Hogan said.

Feedback

Both online and at listening events, participants answered questions developed by Sheffield and research associates Mary Hinch and Dan Schwab about the display.

The text display on the screens was a little jerky, and there was between 8 to 15 seconds of delay between audio and text. Starling said more buffering of the received signal in the radio would help both situations over time.

Interpreters for the deaf and hard-of-hearing were on hand at the events to help with the surveys; participants were asked questions about the captioned text, such as which type fonts and colors they prefer, text placement on the screen and how they would like speakers to be identified.

Participants also were asked how they think emergency alerts should be displayed.

Many participants said they preferred scrolling text rather than the text that appears over a “block” as in TV program captions.