The author is affiliated with Wheatstone, which manufactures the WheatNet-IP audio network.

Anyone who has ever tried to fit a week’s worth of personal items into carry-on luggage understands the problem. It’s impossible to pack audio in the megabits-per-second range into bandwidth in the kbps range without an IP audio codec, and that means losing some bits in the process.

The problem isn’t just that audio comes with a lot of baggage, either. It’s that you can’t always be sure what to pack. Opus, G.722, AAC, they are different algorithms and have different ways of packaging bits for transport across an IP link. You might use brand X on your end of a remote, but that’s not going to fly if it’s brand Y on the far end.

ENTER SIP

Up until now, this has been resolved by simply using the same codec at the studio and at your remote truck or STL at the far end. But all that goes out the window once you want to open accessibility, as is often the case for combining studios across a region or establishing a network operation center in the cloud. Then, it’s hard to control which codec unit you’ll be handing off to on the far end, and it’s an impossible task if you’re handing off to more than one endpoint with more than one codec variation, which can be the case for multiple transmitter sites.

Enter SIP, or session initiation protocol, which is often associated with VoIP communications but also makes a pretty darn good interoperability standard for codecs.

SIP is a signaling protocol used for initiating, maintaining and terminating real-time multimedia sessions.

It initiates a session by sending a message to an endpoint SIP address that can be linked to a physical phone or a software application through a SIP service provider. There’s a header component of the SIP message that conveys information about the message and also a description component (called a session description protocol or SDP) that conveys information such as codec formats.

It initiates a session by sending a message to an endpoint SIP address that can be linked to a physical phone or a software application through a SIP service provider. There’s a header component of the SIP message that conveys information about the message and also a description component (called a session description protocol or SDP) that conveys information such as codec formats.

An “invite” is sent to the far end, and once acknowledged, SIP discovers the codecs in common between the two end points and determines which to use.

[Read: Jay Tyler’s Top 5 AoIP Trends]

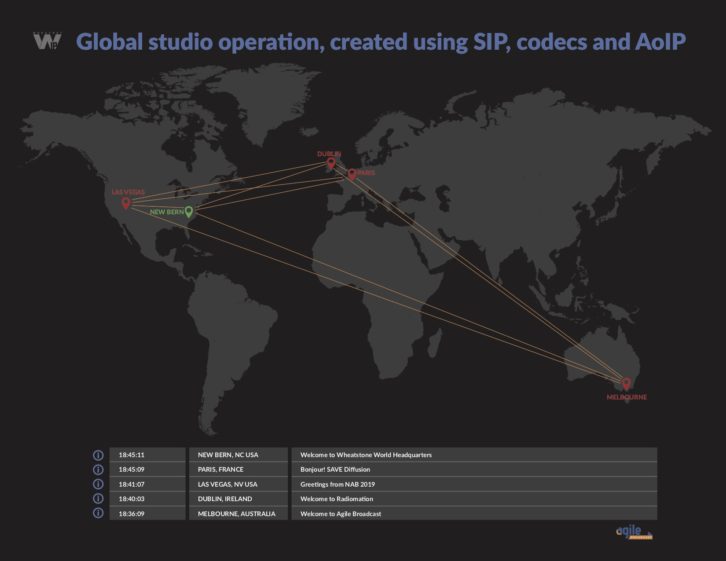

Codec product manufacturers have been interested in SIP for some. IP audio network manufacturers like Wheatstone are also interested in SIP, in part because it makes it possible to seamlessly transport AoIP from a remote sporting or news event to the studio network without regard to codec brand.

IMPLICATIONS

But the wider applications for SIP go way beyond remotes.

SIP is already playing a central role in the next level of consolidating broadcast operations, where for example, one studio is carrying all the programming for a group of stations in a region. It’s likely that some or all of a group’s programming and operating functions will be hosted by a cloud service provider.

Combined with audio control and codecs as part of the AoIP network, SIP solves that issue of getting IP audio out of the studio network and onto the public network for a number of beneficial purposes that will ultimately lead to more flexibility and cost savings for broadcasters.