A commissioner commenting on the FCC proposal to abolish the main studio rule brought up the example of a North Dakota station where authorities claimed “no one was home” when a train carrying dangerous chemicals derailed, jeopardizing the community.

Although the station owners have repeatedly said the story is not true — that the station had responded immediately and the local authorities simply had an outdated station phone number — this 2002 incident underscores an important issue.

In Lock Haven, Pa., WSQV(FM) and WBPZ(AM) are part of a business owned by the Schlesinger family that also includes a music store and a weekly newspaper, all operating from a classic Main Street storefront.

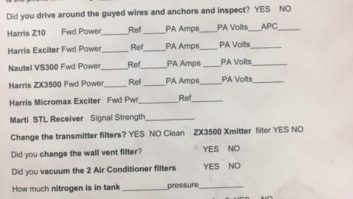

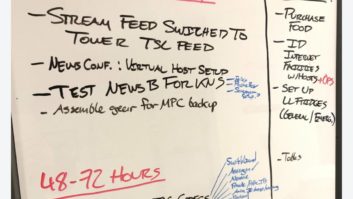

Photos courtesy Scott Fybush

Can a station with no local physical presence maintain ties with its community, especially during an emergency?

We’re about to find out, if the FCC repeals the main studio rule that, for almost eight decades, has required a TV or radio station to maintain a main studio in its community of license.

The FCC started proceedings to eliminate the AM, FM and TV main studio rule in May and opened MB Docket No. 17-106 FCC 17-59 for comments on June 2.

At present, stations are required to have a main studio, a fulltime staff present at the studio, and up until recently, maintain the station’s public inspection files there. If the ruling prevails, broadcasters will no longer need a main studio nor full-time staffing there, but they will likely still need to maintain a local phone number or toll-free number as a service to the community.

WHY NOW?

When the rule was conceived decades ago, local access to the main studio was an important focal point for the community. It wasn’t uncommon for listeners to walk into the studio off the street to talk to jocks on the air or to ask them to spin their favorite record.

Today’s widespread communications have made it so much easier for broadcasters to have an ongoing dialog with the community outside the studio, first through the phone, and more recently, through email and social media.

We might even argue that widespread communications and technology such as IP audio networking now make it possible for broadcasters to participate more fully with listeners and viewers by bringing radio and television out into the community. We’ve seen many examples of this recently, with temporary studios established at county fairs, or at shopping malls or in concert halls, for example. The easy portability of technology like IP audio networking makes this, and so much more, possible.

Meanwhile, the commission already has eliminated many of the primary justifications for the main studio rule. It started with the 1987 deregulation, when stations were no longer required to originate a certain number of programming hours from their studios. A more recent ruling eliminated the necessity to keep public files physically housed at the main studio, making it possible instead to post public files online only.

Now, with this proposed rulemaking, the FCC will release its final hold on the main studio, giving over the responsibility of local radio to the broadcasters who serve those communities.

Will we see windows boarded up and abandoned studios everywhere across the country as a result? Probably not.

Will eliminating the rule make it practical for some co-owned or jointly operated broadcast stations to co-locate their offices? Probably.

Will abolishing the main studio create competitive market conditions that will lead to happier, more productive talent and better local radio? We hope so.

The author is a marketing associate for Wheatstone.