Mitch Bainwol, Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers

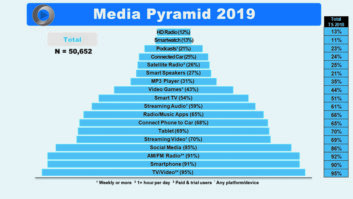

Lawmakers are focused on vehicle safety as the so-called “connected” car becomes more complicated. AM/FM and other forms of “radio” are part of the discussion.

Mitch Bainwol, president and chief executive officer of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, recently testified before a hearing of the Senate Commerce, Science & Transportation Committee covering advanced vehicle technology and its implications. The alliance is a lobbying group for the auto industry and says its members account for roughly three quarters of all vehicles sold in the U.S. each year.

Members include the BMW Group, Chrysler Group LLC, Ford Motor Co., General Motors Corp., Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, Mercedes-Benz USA, Mitsubishi Motors, Porsche, Toyota, Volkswagen Group of America and Volvo Cars North America.

Here are excerpts of Bainwol’s testimony.

The phrase “connected car” has become a bit of a catchall and means different things to different people.

For some, connectivity in the car is about eliminating the gap in access to people or information that occurs when commuting between point A and point B. In our digital world today, drivers and their passengers want to be seamlessly connected to the Web and all its functionality, including social media, communications, music, navigation and a range of transportation-related content. They want to be as connected in the car as they are everywhere else.

For others, connectivity in the car is about reducing the potential of crashes by getting information on real-time risk factors outside the vision of the driver — or the electronic eyes of the car. This connectivity refers to the exchange of information either among vehicles, called “V-to-V,” or information between vehicles and infrastructure, commonly referred to as “V-to-I.”

We believe five pillars of policy are central to maximizing safety through technology in the future:

Protect the spectrum: The first pillar is ensuring that the radio frequency spectrum now dedicated to V-to-V and V-to-I, the 5.9 GHz band, remains solely dedicated to auto communications technologies. When vehicles are driving at highway speeds, communications must occur virtually instantaneously, without delay and without interference.

The FCC is now considering whether to open this portion of the spectrum for use by unlicensed wireless devices. While we understand the potential benefits of expanding wireless access, regulators must be certain that unlicensed users would not compromise the integrity of this vital safety initiative. The FCC should maintain the spectrum for safety critical systems until thorough testing is completed and all parties are certain that the spectrum remains reliable and secure for its primary V-to-V and V-to-I purpose, and can be shared without interference.

Invest in infrastructure: The second pillar is building out the infrastructure for the V-to-I component of connectivity. Surely this will be a gradual process, but we need the vision and motivation to begin planning today. As is the case with a range of technologies, such as alternative powertrains for environmental gains, infrastructure investment is essential to achieving the maximum safety benefit and inducing buyers to purchase the V-to-I communications functionality.

Ensure consumer acceptance: The third pillar is proactively addressing consumer acceptance by addressing in advance of deployment potential public concerns. If the advent of connected vehicle technology exposes drivers and owners of equipped vehicles to loss of privacy, security breaches and/or increased legal liability in the form of automated law enforcement, we will not realize the many benefits that might otherwise be gained by its widespread deployment. Similarly, connected and automated vehicle systems entail interactive technologies for which successful outcomes depend not only on drivers’ correct response to alerts and information, but on multiple entities in both the public and private sectors correctly and consistently performing their respective portions of the connected enterprise.

Maintain vehicle affordability: The fourth pillar is keeping cars and light trucks as affordable as possible by leveraging market forces and utilizing a data-driven approach to regulation if and when needed. Today, the average age of a car is 11 years old, and we only replace about 6 percent of the U.S. car park every year. Policies that discourage the purchase of new technologies should be avoided.

Preserve technology neutrality: The fifth pillar is supporting a comprehensive approach to in-vehicle technologies. Decisions made today can produce dramatic repercussions tomorrow. We all recognize the challenge of distracted driving and how that challenge has grown as connectivity has found its way into cars, primarily through smartphones. The recently issued National Highway Traffic Safety Administration guidelines on distraction are a case in point.

In this instance, government policy calls for restrictions in functionality of in-vehicle systems without corresponding functionality limitations in portable devices. As a result, government policy will likely chill innovation and bias drivers toward the use of handheld devices, rather than integrating devices with in-vehicle systems.

So, if a driver looking for live NAV guidance is blocked from doing so while his car is in motion, he may predictably pull out his smartphone, fiddle with the keys while looking down, and retrieve the desired mapping guidance. That’s the real world, and as much as we might want to wish that away, a policy that isn’t comprehensive across technologies and devices and responsive to consumer needs is a policy that will produce unintended and undesirable consequences.

Successful policy will recognize behavioral realities. We have studied smartphone utilization in cars and found younger drivers are especially resistant to abandoning connectivity while driving. Attempts to modify behavior are unlikely to succeed. Rather, NHTSA has it right when it says that the number one goal in distraction policy should be to encourage drivers to connect their phones to the built-in systems which can be controlled by voice and help drivers keep their eyes on the road and their hands on the wheel.

We are living in an extraordinary moment in the history of mobility. Over the next decade, automakers will put about a billion new cars on the roads around the world — about 150 million of them in the U.S. However, given the size of the in-use fleet and the longer life cycles of today’s vehicles, roughly half of the cars that will be on the road in 2025 have already been sold and put into service.

Thus, deployment throughout the fleet will be relatively gradual even though technology improvements may be rapid. And that suggests that the fleet mix of the in-use fleet will reflect a range of driver-assist technologies and connectivity for years to come.

Bainwol joined the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers in 2001 after leading the Recording Industry Association of America for eight years. Prior to his recording industry career he worked on Capitol Hill for 25 years, including stints as chief of staff for two U.S. Senators, two political committees and several Senate leadership offices. Contact the Alliance at: www.autoalliance.org.