Relatively few Americans are aware of it, but the United States is home to many commercial/religious international broadcasters that transmit programming worldwide using analog shortwave radio transmitters. They are supported by an industry group called the National Association of Shortwave Broadcasters.

Unfortunately, analog shortwave radio transmissions are notorious for interference and signal dropouts. For listeners in other countries, the sound coming out of their shortwave radios lacks the superior audio range of domestic U.S. AM (yes, we said AM) and is often wracked with static and signal fading.

For years, NASB members have wanted to replace (or at least augment) the poor audio quality of analog SW with the crystal-clear sound of digital SW radio, specifically the Digital Radio Mondiale standard developed in Europe that is now being used in China and India.

“DRM sounds very much like FM, with a wide audio range and no static,” said Charles Caudill, president emeritus of World Christian Broadcasting, owner/operator of U.S. SW station KNLS. “It is also consistent: Either the DRM signal is received on your SW radio in full, or it isn’t. There’s no in-between.”

There are some DRM radios in use now, which is why some NASB members are offering limited DRM broadcasts alongside their regular analog SW transmissions.

“But the current generation of DRM SW receivers cost about $100 each, whereas you can buy a cheap analog SW radio for as little as $10,” said Dr. Jerry Plummer, a professor at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tenn., and frequency coordinator for U.S. SW station WWCR. “Given that the audiences being targeted by NASB members are largely in the third world, the lack of inexpensive DRM receivers keeps them listening to analog shortwave.”

Mindful that other digital audio sources are gaining ground even in less-developed countries, the NASB has decided to take action. At its recent annual meeting in North Carolina, at the facilities of U.S. SW broadcaster Trans World Radio, the NASB formed a DRM Receiver Working Group. Headed up by TWR engineer George Ross, this group has been “tasked to evaluate what it will take to get affordable, distributable DRM receivers,” Ross told Radio World. “What is holding DRM up is the lack of affordable receivers.”

CHICKEN-AND-EGG

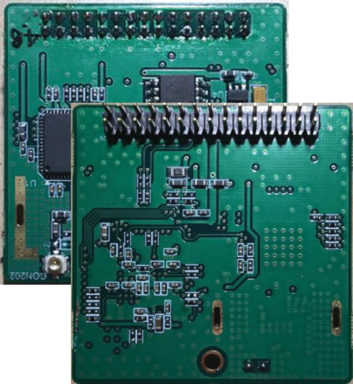

Given the NASB’s interest in low-cost DRM receivers, it was no coincidence that Johannes Von Weyssenhoff was invited to speak at the annual meeting. Von Weyssenhoff said his StarWaves manufacturing firm (www.starwaves.de) has the technology, capability and existing prototypes to build DRM radios for $29 each, but only if the sale order is large enough to deliver economies of scale. (He also estimated $18 DRM modules could be built for installation in other radio models.)

“Twenty-nine dollars is doable at volumes staring at 30,000 receivers,” Von Weyssenhoff told Radio World. “Even smaller quantities would be possible at this price for very simple radios — for example, without graphics displays — but these would be special projects that had to be discussed individually. But even more advanced radios with Bluetooth or premium designs will be possible to offer at a reasonable price,” he said — as long as the sales orders was in the tens of thousands or more.

Given that India and China have committed to the DRM standard, there appears to be a mass-market for these receivers. But the problem for StarWaves is finding the money to build enough of them to drive per-unit costs down.

“In recent years I have tried to convince quite a number of potential investors but either I have not yet found the correct audience, or I was not yet able to communicate this great opportunity convincingly,” said Von Weyssenhoff. “You just have to imagine that alone in India, according to All India Radio, there is a demand of up to 150 million receivers within the next few years. This market could have been served with tons of receivers by now and big profits could have been made, but instead I had to grow the development in very small steps.”

The money StarWaves needs is not huge: “An amount of $150,000 or even $100,000 would certainly do wonders and enable us to start production within a few within a few weeks,” he said. “A commercial order of 10,000 receivers or more would have a similar effect.”

NASB’s members don’t have this kind of money available. Saddled with huge antenna farms and multiple power-devouring 50 kW to 500 kW transmitters, the commercial/religious shortwave broadcasting sector is tight for cash.

“Broadcasting DRM requires either a new transmitter or the modification of an existing transmitter,” said Kim Andrew Elliott, a retired Voice of America broadcaster and host of “Communications World” who has organized many demonstrations of DRM reception at the annual Winter Shortwave Listeners Fest going back to 2003.

“These days, many shortwave broadcasters are thinking about whether they should keep their existing shortwave transmitters on the air, rather than thinking about buying or modifying a transmitter.”

Their situation isn’t helped by the lack of audience measurements detailing SW’s far-flung listener base. Not only does a lack of SW ratings make it difficult to sell spots to advertisers, “but the squeaky, staticky sound of shortwave makes it hard for us to talk to the people at Coca-Cola, who fear that listeners will associate their product with inferior quality,” said Caudill.

The resulting conundrum is a classic chicken-and-egg dilemma. StarWaves and other DRM radio manufacturers don’t have the money to produce DRM radios in volumes that would make them cheap to buy.

“To determine when we can consider broadcasting in DRM, there needs to be a ‘completed broadcast network,’ i.e. broadcasts and receivers,” said Ross. “Without receivers, broadcasts are futile. So broadcasters are still waiting for manufacturing of receivers.”

Jeff White, general manager of U.S. SW broadcaster Radio Miami International (WRMI), said, “We know it’s a chicken-and-egg situation, but no one is willing to invest a lot of time and money into transmitting DRM programs unless they know that there are at least some listeners out there who are able to hear the programs. The other factor is that there are probably billions of analog shortwave receivers out there, and more being manufactured every day in China. So there will still be a large audience out there listening to analog shortwave for a long time to come.”

INEVITABLE?

Despite the hurdles being encountered by StarWaves and the NASB, there seems to be momentum growing for DRM. India’s move to DRM will create a mass-market for low-cost DRM receivers as soon as they become available. Meanwhile, China’s recent DRM deployments has made it “the world’s largest DRM shortwave broadcaster,” wrote Hans Johnson in Radio World earlier this year. “China operates the most DRM transmitters in this band and has the most extensive schedule.”

It is this context that U.S. SW broadcasters are making their DRM push.

“From my knowledge of the situation, many of these broadcasters have been interested in DRM since its inception,” said Christopher Rumbaugh, administrator for the blog DRMNA.info that covers DRM developments in North America. “The reason they are pulling together now is that the time is right for affordable receivers.”

His site posted a recap of NASB 2019 including Von Weyssenhoff’s NASB StarWaves presentation, at drmnainfo.blogspot.com/2019/05/nasb-2019-after-action-report.html.

WRNJ: AM Stations Should Consider DRM+

U.S. international radio broadcasters aren’t the only ones interested in the DRM digital radio transmission standard. WRNJ Radio co-owner Larry Tighe would like stations on the AM band in the United States to have the option of broadcasting using the DRM+ standard if they choose. Licensed to Hackettstown, N.J., “Oldies 1510 WRNJ” broadcasts on 1510 kHz and simulcasts on FM frequencies 92.7 and 104.7 MHz.

Mindful that the current AM band doesn’t have space to add DRM+ stations, he has filed a petition for rulemaking with the FCC, asking that the 45 to 50 MHz section of the VHF spectrum be reallocated for this purpose.

“The 45–50 MHz band was allocated to two-way radio users in business and government, who have since migrated to higher bandwidths where they can use handsets with smaller antennas,” said Tighe. “As a result, this spectrum is extremely quiet right now. WRNJ monitored this bandwidth for an extended period of time, and heard very few distant signals.”

According to Tighe, allowing AM broadcasters to broadcast in DRM+ on 45–50 MHz would vastly reduce their operating costs due to the more efficient broadcast coverage of DRM+, with 1 kW effective radiated power over DRM+ being equal in coverage to 5 kW ERP with AM. His FCC petition argues that allowing AM broadcasters to use DRM on 45–50 MHz would also free the FM band from the thousands of AM-operated FM translators now in use, thus reducing congestion for actual FM broadcasters.

Tighe’s FCC petition acknowledges that DRM+ radio receivers are not widely available to consumers but says that “just like any new spectrum usage, receiver manufacturers will respond to the demand for new receivers.”

It remains to be seen what the FCC’s response to Tighe’s petition will be. Meanwhile, this New Jersey broadcaster also has his eye on the lower half of the once-busy VHF band for AM stations on DRM+.

“There were 660 TV stations between Channels 2 and 7 before the transition to UHF for HDTV,” said Tighe. “There are now only approximately 60 TV stations in the USA on those old VHF channels. There is plenty of spectrum to share with a new service, i.e., DRM+ or any modulation, if the FCC really wanted to move AMs.”