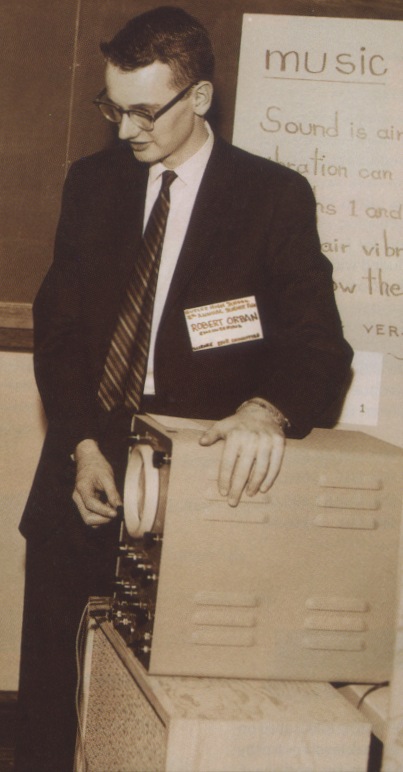

Orban’s first audio processor for FM broadcasting, the Optimod 8000, has turned 50. To mark the anniversary, Orban is sponsoring this series of interviews of Bob Orban in conversation with Radio World Editor in Chief Paul McLane. This is Part 1.

Paul McLane: How did your initial interest in audio develop?

Bob Orban: When I was growing up, if you were technical you were a ham radio kid or you were a hi-fi kid. I became a hi-fi kid. I was also interested in classical music. I had my first reasonably high-fidelity playback system when I was 10 or 11, an RCA New Orthophonic mono record player, a model 6-HF-5 I think, on four spindly legs, with a changer and a ceramic cartridge. It had a hot chassis, with all the tubes’ heaters in series so they could be powered by the AC line — 50C5 on the output and so forth. Cost-saving by eliminating the power transformer was common then.

I started buying classical records, and things went on from there. Later I started building hi-fi equipment from kits. I built a bunch of Knight kits and I built an Eico power amplifier, even built an Eico tape recorder. They had a tape recorder kit back then, believe it or not!

And my first hi-fi speakers were Acoustic Research AR 2s. I heard Quad ESL 57s, which at the time were known as the Quad Electrostatic Loudspeaker, at Harvey Radio in New York City, and I was transfixed by them. They were so transparent-sounding and fast compared to the Acoustic Research that I eventually saved up enough money to buy the floor models from Harvey Radio, along with the accompanying Quad 2 power amplifiers.

And I had a bunch of turntables. I had a Rek-O-Kut, and I think I had a Weathers at one point. I also had a Rabco linear tracking arm. Stereo had started about the time I was getting into high school, 1959. The first stereo records were in ’57, I believe. So I was into stereo early on.

I also was interested in amateur recording. I was a member of a little instrumental ensemble. Unlike most kids today, we played pop standards, the so-called Great American Songbook. I played piano, and we had a drummer and a trumpeter. We weren’t very good, but that inspired my interest in recording. I recorded all of our high school spring musicals, band and chorus performances. The first one that I recorded, I was still in eighth grade. I was going to become a high school student next year in Butler High School in Butler, N.J. So my first recording of a spring musical was, I think, 1958.

McLane: You were already thinking audio and music. Did you have an entrepreneurial bent?

Orban: Not really. As I moved through high school, I found I had a knack for math and physics. I was going to be a physicist. When I entered Princeton I was a physics major for the first two years, but found that real professional physics requires a Ph.D.

Somebody said that being at the math department at Princeton was like drinking water from a fire hose. That was what the Princeton physics department was like, too.

So I decided to change my major to electrical engineering. Fortunately, the required courses for the first two years of the physics track and the EE track were similar in terms of the mathematics and so forth, so it wasn’t hard to make the change.

McLane: Yet by that time, you had already been involved in making a stereo synthesizer.

Orban: I’d become part of the student radio station at Princeton, WPRB. It was unusual for college radio because they had a commercial license at 103.3, with 17 kilowatts. We were semi-independent of the university. It was owned by a board of trustees, and we mostly financed the station by selling advertising. It had a big reach with that 17 kW signal.

I was mostly in engineering, but I also did a classical music show weekly for at least three years, and I was music director for one year. I got to choose not only classical programming but a lot of the popular music programming. I was a pretty good, tight, rock-and-roll board operator. I engineered a show with personality Rick Rosenthal, who later became well known as an anchor at WGN (TV) in Chicago in the news department.

Back then, it was tape cartridges and slip cueing on turntables. I actually built a couple of cartridge machines for the station, and I built my first compressor using optically coupled gain cells with cadmium sulfide light-dependent resistors.

But the story of the stereo synthesizer — I was at an Audio Engineering Society meeting in New York City, and one of the speakers was the famous and distinguished acoustics Ph.D., Harry Olson of RCA Labs.

I saw him checking a train schedule. RCA Labs was in Princeton, so I perceived the opportunity and introduced myself and offered him a ride back. We had a chance to chat for about 40 minutes on that drive back from New York City to Princeton.

He said that RCA Labs had a sort of junk building where they had all the castoffs on their various experiments. I told him of my involvement in the radio station, and he said, “Come on by and go through it and see if there’s anything you need.”

McLane: Toy store!

Orban: Yep. One of the things I found was a 90-degree phase difference network, a pair of all-pass filters designed to produce a 90-degree phase difference throughout the audible range.

I’d previously had the idea to make fake stereo by synthesizing a stereo difference channel. The reason we did this was that the radio station was playing rock and roll singles, which was fairly unusual for FM at the time, but all the singles were in mono, and in 1963 we had converted to stereo FM transmission, which was very early in the game for college radio.

We wanted to be able to play those singles in fake stereo. So my first attempt at doing stereo synthesis was just to EQ the mono and create a stereo difference signal. But that didn’t work all that well; the effect was weak.

Once I had this 90-degree stage difference network, I decided to find out what happens if I take one side and use that to generate the left minus right. And lo and behold, there was this very dramatic sense of space. It turns out that it created a complementary comb filter, so I built my own all-pass filter that I could tune for maximum effect.

That was also my first patent and my first AES Journal article. I proved mathematically that if the synthesized L minus R is all-pass, not only is the sum of the two channels the original mono — which is pretty obvious, because it’s just how the matrix works — but also the sum of the power spectra of the two synthesized channels is equal to the power spectrum of the original mono. So it maintains the EQ texture of the original, which honors the intent of the creators as well as you can while still creating artificial stereo.

That’s the long story of how the Orban stereo synthesizer came to be.

McLane: This is the late 1960s, getting toward the time when you got your master’s degree, and you started Orban Associates. You started marketing products along with the folks at Parasound.

Orban: The stereo synthesizer I believe I developed in 1966, when I would have been a junior at the university. Fortunately, my father had a steel and machine tool import/export company, so he was willing to finance a bit of entrepreneurship for me. After I got my master’s degree from Stanford in 1968, I started hand-building and selling stereo synthesizers.

Shortly thereafter, I met my business partner, John Delantoni, who had been involved with a contract manufacturing company called Diphase.

He said, “Your stuff looks like somebody made it in their basement. I can help you make something that looks a lot more pro.” I thought, “Okay, why not? This sounds like a good partnership.”

In fact, it endured until the company was sold to AKG in 1989. He died at an unfortunately early age shortly thereafter. But he was not only a good friend but very important to my business success.

McLane: The two of you were Orban Associates?

Orban: We were the Orban Associates division of the Kurt Orban Company up until 1975, and John remained a contract manufacturer until then.

I think we were only doing about $300,000 a year in business with the Orban/Parasound stuff. He said that to make it worth his while, he would get have to get more fully involved and have co-ownership in the business.

So in 1975 I arranged with my father to spin off the company and pay the money he had invested in it up to that point. And fortunately, around that time I was involved in developing the Optimod 8000, so we soon had the funds to do it.

McLane: In the meantime, didn’t you have an important success with parametric EQ as a separate product?

Orban: I had been asked to chair a session at one of the AES conventions. I was young and naïve, and I thought that people would just come to me. But you really had to struggle just to get enough papers to fill up the session. You had to reach out to people and ask them for presentations.

I’d heard that George Massenburg had developed this parametric EQ, so I invited him to present. And that gave me the idea that I could use something at a more affordable price, because George was basically going for the top end of the market, very high-quality amplifiers and so forth. I didn’t want to copy his circuitry exactly, because I thought that would be a little “déclassé” after I invited him to give his paper! So I developed my own way of doing parametric EQ.

But I certainly want to emphasize that George was the inventor of the concept.

McLane: This was the model 621. I understand it was pretty impressive.

Orban: Originally they did not have built-in power supplies. I thought people would be likely to buy a lot of them to retrofit them in consoles, and they’d want just one power supply for all of them. Eventually we had to come up with a power supply that people could buy also. Then later we came up with the 622, which used yet another circuit that wasn’t George’s but had a built-in power supply.

But the parametric was not the only important Orban/Parasound product. The de-esser was probably equally as important. I had been involved in some professional recording at the time, and in the mix sessions I observed, I saw the need for a music recording-focused de-esser to support the crisp vocal EQ that was becoming popular.

I’d met Paul Beaver and Bernie Krause around 1970, and we had engaged them to be the rep for the Orban/Parasound product line. Eventually I had a chance to mix some of their records.

In fact, as a side note, the last two albums they did for Warner Bros., “Gandharva” and “All Good Men,” were mixed in quadraphonic sound. Those have just been released on the Rhino Quadio label in April. It’s really gratifying for me, 50-plus years later, that this work should finally be heard by public and fans of Beaver and Krause in the original discrete quad format.

Not only that, but Warners lost the quad masters to “All Good Men” somehow. I don’t know if they lost them in the Universal fire or if they were just misplaced. But fortunately, I had safety copies preserved in my basement for over half a century. So that’s what finally got used for the “All Good Men” re-release.

I am also pleased that there was a short film made of the Gandharva sessions at San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, which survived and can be seen on YouTube. I’m briefly visible, looking impossibly young!

McLane: That’s wonderful. Now, how did you get from classical music, pro audio, parametric EQ and de-essing into FM processing?

Orban: Back when I was at the student radio station, I had already made my first compressor using an opto-coupler, with a Fairchild Conax as the peak limiter and high-frequency limiter part of the processing chain. But then when I moved to California to get my masters in EE at Stanford, a pair of my friends from the station in Princeton moved to California at the same time as I did. Lee Gahagan, who had been station manager at one point, wanted to be in commercial broadcasting and had purchased KPGM in Los Altos. Jeff Schaffer came out to get his law degree at Stanford.

As a class project as part of my master’s degree, I had done my first FET compressor with program-controlled time constants. That became the broadband compression part of my “overload prevention system,” which I had built for KPGM.

This was my first processor that included a full FM processing chain. It just used a pre-emphasized clipper for the high-frequency control. Among a bunch of other interesting Orban history, there’s a picture of it at www.261.gr/orbanmus.html. It later showed up in somebody’s back room and it’s now in the Orban history racks again.

When we put this thing on the air, it wasn’t controlling modulation very well. I knew that it was controlling the peaks perfectly at its output — I could put a scope on it and the peaks were nice and flat — but looking at the new Belar modulation monitor they had at the time, on things like Bert Kaempfert’s “Wonderland by Night,” the muted trumpet was going up to 130% modulation. I called Arno Meyer at Belar and asked him, “Why is this happening?” He said, “Oh, the overshoot is caused by the ringing in the low-pass filters of the Collins stereo generator.”

I thought, “Well, we have to deal with that problem. So how am I going to make non-overshooting low-pass shelters?” I gave that some thought, made some experiments, and finally came up with something that worked pretty well, put it on a breadboard, and lo and behold, you could put that on the air, and the overshoots went away.

McLane: Were you working at home on a workbench? What was your actual physical setting?

Orban: I lived in a studio apartment in East Palo Alto, which didn’t have enough room, so I ended up with a little workbench in a corner of KPGM, which I rented from Lee. I didn’t have a home workbench till I moved into a rented house in Menlo Park in 1970.

At this point, Eric Small comes into the picture. Eric was a well-known consultant in New York City and specialized in making radio stations loud.

He had a lot of instrumentation. He was doing interesting things with CBS loudness meters and the like, and he had been hired by the Nippon Columbia people to be the technical supervisor for the quadraphonic FM tests being done at that time experimentally in order to file with the FCC. The Nippon Columbia was Duane Cooper’s invention. In turn, Eric hired me to be involved as part of that, so that’s how I got to know Eric.

I showed this mono breadboard to Eric, and he put it on his Belar, and he was mightily impressed. He thought this thing had big commercial potential. The one problem that it didn’t solve was how to bypass the low-pass filters in the existing transmitter stereo generators. I told Eric that the logical way to solve this was to incorporate the stereo generator into the audio processor, which no one had done yet.

Eric mulled it over for a while and finally agreed with me. The concept of the 8000A was born, and John Delantoni and I worked out a distribution agreement with him stipulating that he would be the representative for it.

The problem was getting this through the FCC, which back then heavily regulated the performance of transmission equipment with type acceptance and type approval. At the time, the composite STL concept had just been approved by the commission.

So Eric suggested that we make the stereo generator look like the output of a composite STL to exploit the precedent. Eric did all the liaison with the FCC. I did the proofs and he filed them.

I was a hi-fi kid, Eric was one of those RF kids. He knew how to RF-proof things. He taught me how to make RF-proof packaging. The first prototype 8000 used Eric Small-inspired RF proofing. That’s why it worked okay at the various transmitter sites that we tested it at.

McLane: Who came up with the name?

Orban: That was me. I remember driving back from San Francisco and thinking about what to call it. There was Audimax, three syllables, Volumax, three syllables. So I thought, “Optimod.” Optimum Modulation.

It’s the classic combination of the familiar and the new, which is always the trick to making a hit record.

McLane: And how did you decide on “8000”?

Orban: Intel had the 8008 and then later the 8080, so 8000 was a hot number in tech at the time. Again, it was a combination of the familiar — but we weren’t going to copy it exactly — and the new. And of course, it wasn’t a microprocessor. It was an audio processor.

McLane: What do you remember about the initial market reaction to this product?

Orban: Great excitement. Eric had demoed the prototype with a number of important stations and had done measurements indicating that it gave a 3 dB loudness increase over the classic chain that people were using, which was typically Audimax and Volumax driving a transmitter with its built-in stereo generator and exciter.

Moseley, I believe, had stereo generators at the time that were standalone. Gates had the TE-3 exciter and RCA had the “Iron Fireman.” Collins had the high-quality 830 series. But they all had low-pass filters with overshoot. Compared to those chains the Optimod was giving 3 dB more loudness effortlessly. This highly transparent FET limiter had about one-tenth the distortion that the Audimax/Volumax chain did.

I’d hoped to bring a more high-fidelity sound back to the FM band, and one of our first marketing pieces made the audacious claim that “it would have made Major Armstrong very happy.”

But, of course, it never actually works like that. People started putting stuff in front of the 8000. I think the Dorrough DAP was already around at that point or shortly thereafter. So people were putting DAP 310s in front of them. And a number of people were rolling their own, like Bob Kanner, who had the very famous AM audio chain at KFRC, and I believe KHJ in Los Angeles, the RKO station at the time. And he wasn’t the only one.

McLane: Were loudness wars already a thing?

Orban: Oh, absolutely. Eric was from New York City, which was where the loudness wars originated. WOR(FM) had gone to a rock-and-roll format in 1966, and that’s where I sold my first stereo synthesizer. Like WPRB, they needed it for mono singles.

But by the time we had gotten to 1974, when I developed the 8000 and when the prototype started bicycling around from one station to another, rock-and-roll had been on the air in New York for almost 10 years. And they were doing it in Detroit, they were doing in Los Angeles and to a certain extent, in San Francisco, but not so much — San Francisco had KMPX and it was still sort of underground at the time. But the loudness wars were definitely a thing.

McLane: Do you remember how much that first Optimod cost to buy?

Orban: It was about $3,000. And we increased our sales by an order of magnitude in one year. We started doing $3 million a year instead of $300,000.

Eventually we started our own marketing department and moved on from Eric Small and Parasound. There were some hard feelings there, but unfortunately that’s business, and as we grew we needed to bring our marketing in-house. We had a series of good marketing folks, Jesse Maxenchs, Sid Goldstein and many others over the years. And Orban continued to grow.

Next time: The early Optimod years. Read Part 2.