Fig. 1: A routine site inspection found this frozen air conditioner. Armed with a cell phone for pictures, Steve Tuzeneu recently visited all the transmitter sites for Townsquare Media Grand Junction, Colo., where he is the new market chief.

At one of the sites, Steve found the air conditioner frozen (shown in Fig 1). Turning the unit off will allow it to thaw out.

Steve’s visits are a reminder of the importance of regular site inspections, especially coinciding with the change of seasons.

Be sure to take your camera or phone along. Document issues to help the GM see how you are caring for the station as an investment.

John McKenna is director of technology and engineering for the YES Network, “Where Yankees Fans Get Their Yankees!”

He commented on our sad story about the engineer who vented his transmitters only to realize that “backflow” outside air had damaged the components of his idle standby unit.

John was surprised that whoever installed this air system hadn’t put a set of louvered shutters on the outside of the vents. These “backdraft dampers” are almost universal in colder parts of the country, venting anything with a blower — such as a transmitter. Not only do the louvers prevent backflow of air, but they keep cold air out of the building if the transmitter is off overnight.

When the blower comes on, air pressure moves the shutters open, allowing the heated air to pass to the outside. When the transmitter shuts down, the shutters close and prevent outside air from coming back through into the equipment.

In the example in our previous column, backflow through the non-operating transmitter would create a negative pressure in the duct and serve to pull the shutters closed even more tightly. This would keep the moist outside air from the equipment.

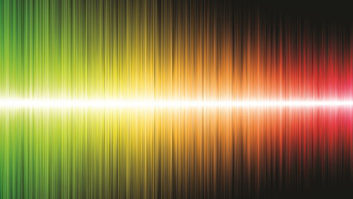

Fig. 2: A backdraft damper protects transmitter equipment. As you can see in the illustration marked Fig. 2, there’s a little V-shaped bend at the bottom of the louver to allow it to close rather tightly around the hinge of its mate below. This does a pretty good job of sealing the opening when it is closed. Any wind blowing against it or negative pressure on the backside will force the louvers even tighter.

Of course, the picture is for one that has the airflow coming from inside the building, but there are versions with the mounting flange on the other side to protect air intakes, as well. Note that these can blow open occasionally, should the wind blow right at it, and there’s no positive pressure on the inside. An alternative is a hood.

Most HVAC guys will put a hood on the outside, to hide the opening from weather, and a trap inside the building to catch any precipitation that gets forced in, so it doesn’t blow into the gear.

Installing a backdraft damper is a lot cheaper than constantly running the blowers on the spare transmitter and potentially causing belt or bearing failure. If you are using outside makeup air for cooling, put a set of shutters, opening into the plant, at the intake port to keep the outside air out when it isn’t needed. This saves on air conditioning and heating costs.

For recommendations, John suggests you contact either an air conditioning mechanical company that does sheet metal or an AC supply company.

From time to time, entry-level engineers ask me for advice on good broadcast engineering reference books.

Ben Dawson of consulting engineering firm Hatfield and Dawson ranks the “Radio Engineers’ Handbook” by Frederick Emmons Terman as a must-have. Ben says this book was printed by the tens of thousands during World War II (evidently at the behest of the military) and copies can often be found in independent used bookstores for $10 or $15.

Over the years, Ben has purchased a number of copies and distributed them to folks all over the world. It is, in Ben’s opinion, the one book no radio technician or engineer should be without. Ben recently looked at Amazon’s website, which showed it available for about $12.

The next most useful book, for the RF side of broadcasting, is B. Whitfield Griffith’s “Radio-Electronic Transmission Fundamentals.” It was published in 1962 by McGraw-Hill and reprinted a few years ago by Noble. Amazon has it for $80 or so new, about half that used. Powell’s in Portland (in my opinion, the best bookstore in America, maybe even in the world — better than Foyles in London, which was the best for many years) often has it too. The reprinted edition also has the answers to the problems, too.

Ben notes that he and Ron Rackley got Noble to reprint Griffith’s book, and it has an introduction from both consultants, though they didn’t receive a commission. In fact, it cost both engineers, who had to slice up a copy to be used for reproduction until it was discovered that Whit had the original page proofs, which he graciously supplied for the reprint.

For those who want to understand modern analytical methods for antenna analysis, in Ben’s view you can’t beat Warren L. Stutzman and Gary A. Thiele’s “Antenna Theory & Design.” Ben knows folks who’ve taken classes from one or the other (Stutzman at Virginia Tech, Thiele at Ohio State/University of Dayton) and say they were great teachers; this book demonstrates it. There are at least two editions; it can be found used for under $50.

Ben writes he could go on (as the Hatfield and Dawson office library has about 2,000 books!), but if he were on some deserted island, these would be his choice of textbooks. What are yours?

Send Workbench tips to me at [email protected] or fax (603) 472-4944.

Contribute to Workbench. You’ll help your fellow engineers, and qualify for SBE recertification credit. Author John Bisset has spent 45 years in the broadcasting industry and is still learning. He handles West Coast sales for the Telos Alliance. He is SBE Certified and is a past recipient of the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award.