Responding to Kevin Curran’s commentary titled “EAS Is Still Relevant as WEA Works Out Kinks” in the Aug. 2 issue of Radio World:

Kevin, referring alert recipients to local media outlets is a hard sell. If they can even access a local source, most stations likely will not be carrying information about the alert but airing routine programming. It all depends upon when one listens, and to which station.

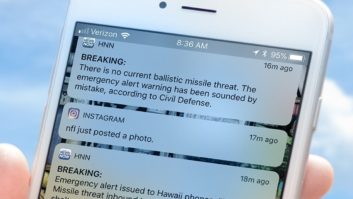

I was at the Lake County Fair last week when an Amber Alert was sent to cellphones. All necessary information was provided. But the location involved was several counties away. If I’d tuned to local terrestrial stations, I doubt I would have received useful information about this alert.

Your article defined several barriers to EAS alerts to the public. You pointed out that time shifting on DVRs is a common problem; that internet TV offers no EAS, so cable cutters will not see an alert; that Bluetooth listening to a playlist is not serviced by the EAS, nor are Wi-Fi-connected automotive users.

You noted that the EAS over-delivers on affected areas, making messages ineffective; that TV stations are over-covering large areas, with the same result; and that alerting agencies other than the National Weather Service are not practiced in alert delivery, thus alerts can be incorrect or missing entirely.

RESPECTIVE STRENGTHS

The strength of terrestrial EAS is in its wireless daisy chain for delivering long-form alert information. Critical Primary Entry Point and Local Primary stations are part of a defined monitoring network that links the wireless terrestrial broadcasters for ad hoc emergency traffic dissemination. This is a strength — and it is the inverse of the cellular network, which will fail soon after power outages.

But many terrestrial radio stations today are “storefronts,” with no humans present. Many at times are simply automated PCs playing the hits. Many stations in the continental United States have chosen or been forced to cut costs to the operational skeleton. As a result they are not offering live delivery and at best may offer satellite-delivered newscasts. They meet minimum compliance requirements with an automated EAS device. And the only alert requirements, by regulation, are a weekly test, monthly test and standby for an EAN. Everything else is voluntary.

Further, terrestrial media search results vary by time of day and formats available. In my county fair example, no one had a radio nearby. An exception would be smartphones with FM receivers enabled. But most users would search the web for follow-up information, not attempt a terrestrial search.

Morning radio is well manned, of course. In the Chicago market, 30 live morning shows are available on weekdays. Major markets have all-news formats if you know where to look. Often these are AM/FM simulcasts. When all else stops, terrestrial radio, in particular AM radio, will be on air as the last delivery system. Those cellphones will become paperweights as cell sites go dark and user’s batteries expire.

The cellphone text alert is the front line of alert dissemination. It supersedes terrestrial broadcasting in that millions of smartphones are carried and monitored 24/7. Cellular alerting’s strength is the ability to store an alert for review, which is not an option for terrestrial broadcasters. Expansion of text to 360 characters is a good step to making the user decide what to do; it would be even better if multiple languages could be selected by the user.

A press release from FEMA reports that the planned September CONUS EAS test will use the same process as the previous one. So yes, the NPT (National Periodic Test) code test will work well using CAP via internet. This is a cellular alert to which the station’s equipment responds via IP connection. It is an IP test, not an EAS test of the wireless daisy chain. It is a valid test NPT event code.

But the NPT is not a test of the state daisy chain plans via the PEP radio station network. It does not use the Emergency Alert Notification code, a hot code for national alerting so that the president can send an audio (voice) message to the American people within 10 minutes of a disaster. The September national NPT code test by FEMA and the FCC avoids such an end-to-end EAN test. Until you use the actual hot code, the system is not tested and you don’t know if it will work.

STATE PLANS

This opens a discussion of state EAS plans. How do you make voluntary SECCs compliant with FCC rules? Each state developed its own relay plan and performs the RMT via that plan.

The only CONUS EAN end-to-end test was in 2011 and it did not turn out well due to an audio issue. For a system that has been in place in one form or another for over 62 years, an end-to-end EAN test is overdue.

Many threats face the continental United States. Power grid attacks, EMP events and earthquakes are a few of the obvious wide-scale “system” failures that would warrant a CONUS alert. It’s for this reason I felt the EAS initial short-form “door-bell” alert should be taken off the backs of terrestrial broadcasters and cable operators.

Kevin, you wrote, “With cellphones in just about everyone’s pocket, it would seem that WEA could replace the other mass notification systems.” I agree with that 100 percent. Can we hope the Washington bureaucrats will see through the fog of alerts and warnings, and come to a similar conclusion about a rewrite of Part 11?

For an excellent review of EAS, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emergency_Alert_System.

The author, a retired broadcast engineer, is former chair of the Illinois State Emergency Communications Committee and was a board member of the Primary Entry Point Advisory Committee.