It’s been more than two years since my article about Reginald A. Fessenden and what may have been the world’s first broadcast appeared in Radio World.

Readers will recall that in the last months of his life, Fessenden claimed to have sent out a short program of speech and music on Christmas Eve, 1906, with reception reports being received from as far away as Norfolk, Va., nearly 500 miles away.

He also claimed that a similar broadcast conducted a week later drew response from the West Indies, more than 1,500 miles from his Brant Rock, Mass. laboratory.

This was a great account and one I had enjoyed telling and retelling for some 40 years. However, even after much investigation, only a single document could be found to substantiate Fessenden’s claim.

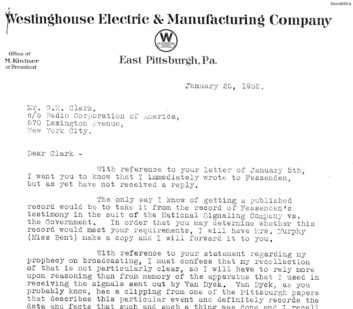

This was a letter dated Jan. 29, 1932 from Fessenden to Sam Kintner, a Westinghouse vice president. It apparently was written in response to an inquiry from Kintner about Fessenden’s involvement in broadcasting-related activities.

I left my 2006 article “open ended,” hoping that someone might come forward with some artifact that would bolster Fessenden’s claim and settle the matter, especially as Fessenden had declared that many heard the transmissions and that proof existed in the form of multiple ships’ logs (and supposedly the letters he received from ear witnesses).

While my article generated a lot of response, no one has yet come forward with proof positive of the event. To the contrary, additional evidence surfaced that would tend to disprove the Christmas Eve story. Some of it even offers a clue at to what might have really happened.

Francis Hart demystified

One of the more interesting artifacts uncovered during my 2006 research was a radio log kept by Francis A. Hart. It had been donated to the Smithsonian Institution in the 1960s and little was known about it.

Hart started the log in the fall of 1906 and it spanned roughly three years, providing a wealth of information about what radio was like 100 years ago. I decided to prepare an article about the log itself, and in the process, discovered that Hart’s son, Burton, was still alive. Burton and another radio history buff, George Flanagan, were able to provide a great deal of insight into the elder Hart’s life.

To correct an earlier assumption, Hart, at the time he kept the log, did not live in Sayville, N.Y. His early life was spent in Brooklyn, some 45 miles to the west. Hart had a strong interest in wireless, and as this was something of a novelty then, he and his amateur station were the subject of several newspaper articles. These revealed Hart was not just a DXer; he was also frequently “on the air.”

The newspaper clippings also provided the following information:

- Hart was able to copy radio traffic from as far away as 1,400 miles on a fairly regular basis.

- Most evenings, he made it a point to “listen in” to a daily 10 p.m. news feed from the Marconi land station at Cape Cod that was sent to ships crossing the Atlantic.

- Hart exchanged QSOs with commercial stations, including a Fessenden operation. (This was perfectly legal then.) According to the newspaper report he worked all such land stations within a 20 mile radius of his home (the limit of his transmitter). He “checked in” almost every evening.

- Hart was able to tune both “regular” and “long” wavelengths with his receiving apparatus.

- He had access to an antenna (some three miles long) that would have favored the long wavelengths Fessenden used.

I reported that Hart logged no unusual traffic on Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve or any time around these dates in 1906.

As the newspaper articles establish that Hart was in an excellent position to have heard the broadcasts, or at least the fallout from them, it seems inconceivable that he would not have been aware of Fessenden’s “broadcasts” and made some sort of log entry about them.

Other searches

Part of my research for information on the broadcasts had involved the Smithsonian Institution, and in August 2007, I received a call from Elliot Sivowitch, an emeritus curator with that organization, informing me that some additional material had been located that might be of interest.

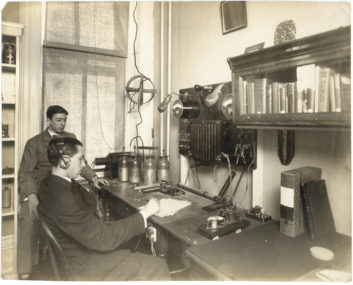

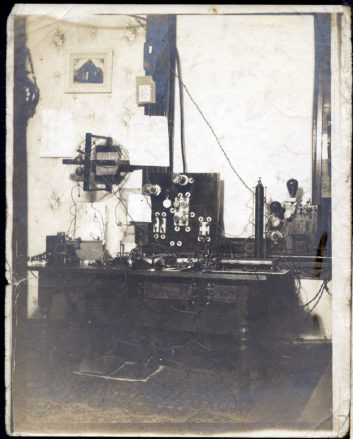

Hart’s wireless station, constructed in his bedroom. Object at right near panel with darkened lamp bulbs appears to be a tuning coil for low-frequency (LF) wavelengths. This would have allowed him to hear Fessenden’s alternator transmissions. The wall calendar places the date as May 15, 1907. Courtesy of George Flanagan

These were copies of an exchange of letters between George S. Turner, chief of the FCC’s field engineering and monitoring bureau in the 1950s, and Joe E. Baudino, a Westinghouse Broadcasting Co. vice president.

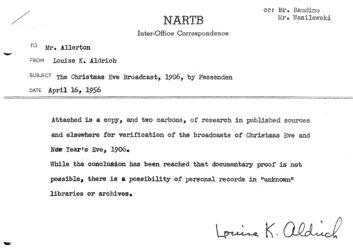

The Smithsonian papers also included a lengthy report from Louise K. Aldrich to a “Mr. Allerton.” These were employees of the National Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters (NARTB), now the National Association of Broadcasters. The report was dated April 16, 1956 and was “cc-ed” to “Mr. Baudino” at Westinghouse.

In examining this new information, it became readily apparent that the research conducted by myself and others in 2006 into the authenticity of Fessenden’s claim was not the first.

The papers indicate that early in 1956, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the “broadcasts,” Westinghouse’s Baudino was interested in corroborating Fessenden’s 1932 account, enlisting the help of both the FCC and NARTB. The long and short of it is that even though the investigation continued through 1957, Baudino did not get his wish.

Aldrich’s 12-page document indicates that she not only searched many U.S. and foreign publications for evidence, but also reached out to many other sources, including the U.S. Navy and the United Fruit Company for their ships’ radio logs.

In addition to searches of periodicals and Fessenden’s collected papers, Aldrich also approached a still-living Fessenden contemporary, Major Theissen. He’d served as an assistant to Fessenden, and in 1956, lived in the Washington area and was a member of the board of the Fessenden Foundation.

Theissen related that he “thought the broadcast had occurred” and provided Aldrich with a possible published reference. This didn’t pan out either.

Aldrich summarized her investigation with the following statement.

“From the search just described, while not an exhaustive search, it has been concluded that neither the Christmas Eve broadcast nor the New Year’s Eve broadcast of 1906 was noted in newspapers, magazines or in scientific papers on wireless telegraphy. Nor did Dr. [sic] Fessenden refer to the broadcasts in any of his writings during that period.”

Aldrich, in her memo accompanying the report stated:

“While the conclusion has been reached that documentary proof is not possible, there is a possibility of personal records in ‘unknown’ libraries or archives.”

The FCC’s Turner also stayed busy in contacting early radio people who might have firsthand knowledge.

One of these was Tom Stevens. He stated:

“…I am afraid that I cannot confirm the information you are seeking re the Fessenden experiments with radiotelephony. I was discharged from the US Navy at Provincetown on October 12, 1906 and had returned to my old home town of Austin, Texas. I was working for the DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company of Texas at San Antonio during the Christmas Season of 1906. I did not hear BO – Brant Rock transmit radio telephone signals at any time. However, I heard that station sending the letter D on many occasions and also heard it send test messages many times.”

Another old-timer contacted was Harry Gawler. He reported that while he thought others might have heard such broadcasts, he had no direct knowledge.

“I was in Chicago around Christmas reporting on the wireless activities going on there for Fessenden, so I only know of the telephonic tests [this is a reference to the Dec. 21 Brant Rock radiotelephony demonstration] by what I was told upon my return to Washington.” [Fessenden’s company, NESCO, had an operation there.]

Gawler provided several names of those that might be able to substantiate a Christmas Eve broadcast, but these apparently led nowhere. The exchange of letters between Turner and Baudino ended in December of 1957.

George Clark

In my 2006 research I discovered a 1936 memo in the George Clark collection at the Smithsonian that captured the recollections of three radio pioneers (Arthur Van Dyck, H.E. Halborg and John V.L. Hogan) concerning the “broadcast.” It had obviously been prompted by Clark. (George H. Clark was active in early radio, a long-term RCA employee, an historian and a pack rat of the first order. During his lifetime he obtained and saved an enormous amount of radio-related photographs, letters, memos and other documents.)

The Clark collection also contains the “copy” — the original has never been located — of the Jan. 29, 1932 Fessenden/Kintner letter.

In additional searching of the Clark collection, I found two documents that indicate Clark was eager to learn the truth about the “broadcasts.”

The first is a letter dated Jan. 25, 1932 from Kintner to Clark. It covers several bases, but the first paragraph is quite interesting as it strongly suggests that it was actually Clark who prompted Kintner in early 1932 to contact Fessenden about his broadcasting activities:

“Dear Clark — With reference to your letter of January 5th, I want you to know that I immediately wrote to Fessenden, but as yet have not received an answer.”

We know, of course, that Fessenden did respond four days later.

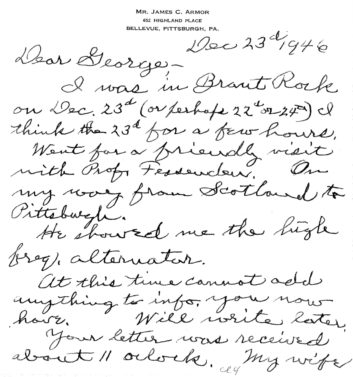

Even after receiving Fessenden’s response, Clark seems not to have been satisfied, as indicated by the previously mentioned 1936 memo. The second letter I located indicates that Clark was still questioning the broadcasts well into the 1940s, as it is dated Dec. 23, 1946 and was penned by James C. Armor, another former Fessenden employee.

“Dear George — I was in Brant Rock on Dec. 23d (or perhaps 22d or 24th) I think the 23d for a few hours. Went for a friendly visit with Prof. Fessenden. On my way from Scotland to Pittsburgh. He showed me the high freq. alternator. At this time cannot add anything to info that you now have. Will write later.”

To make more sense out of this, Armor was at the NESCO station in Scotland in early December 1906 when the 420-foot antenna there was destroyed in a wind storm. With the loss of the antenna, the station was closed and Armor returned to the United States. It is inferred that he sailed to Boston and decided to pay Fessenden a Christmas weekend visit before he traveled on to his home in Pittsburgh.

This letter puts Armor at Brant Rock just after the Dec. 21 radiotelephony demonstration and close to the time of the “broadcast.” It would have been a natural flow of things for Fessenden to mention the planned broadcast and to have invited Armor to witness it. But this didn’t happen.

Fessenden’s radiotelephone equipment

Readers may remember that Fessenden performed a demonstration of his radiotelephone system for invited guests on Dec. 21, 1906, three days prior to the first claimed broadcast.

Letter dated Jan. 25, 1932, from Sam Kintner to George Clark, indicating that it may have been Clark’s search for the truth about the Christmas Eve event that sparked Fessenden’s Jan. 29, 1932 letter in which he declared that he did it.

This event basically was for the benefit of telephone company people, as he was trying to convince them of the merits in expanding the reach of their system with radio. However, others were also present, including members of the press. The demonstration involved the radio transmission of speech and music to a receive site located in Plymouth, Mass., with demodulated audio also being returned to Fessenden’s Brant Rock transmitter site via telephone lines. The successful test was well documented and is mentioned in Fessenden’s Jan. 29, 1932 letter to Sam Kintner.

My store of Fessenden information was greatly enhanced with a copy of the telephone company engineering report on this demonstration provided by radio historian Alan Douglas.

The report is dated Dec. 24, 1906 and was issued from Boston. It contains full technical details of equipment used, what was demonstrated, sketches of apparatus and schematic drawings. It also notes that Fessenden had prepared a “handout” for attendees. The report is unsigned, but it is speculated that it was prepared by Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, a telephone company engineer.

The document notes that Fessenden’s alternator was running at “50,000 cycles,” and while designed to produce 300 W, the actual output, as measured, was only 36 W. The report says 24 of these were dissipated by the modulating device (carbon microphone), leaving only 12 W of RF to feed the antenna.

The depth of modulation was not especially impressive either:

“It was stated by Prof. Fessenden, and seemed probable to me, that the present transmitter (microphone) only varied about 5% of the total radiated energy.”

Of particular interest is an estimate of transmission distance that Fessenden may have been able to accomplish then. (Recall that the receive site for the demonstration was in Plymouth, Mass., some 10 miles from Brant Rock.)

“The alternator, altho [sic] operating at 50,000 cycles, was designed for 100,000. At this frequency [100,000 Hz], the radiation from the antenna, other factors remaining the same, is greatly increased. As the radiation increases with the fourth power of the frequency, this doubling of periodicity would increase the radiation sixteen-fold, and, as the range varies with the square root of the radiation intensity, the distance of communication would be increased four times. This would mean about 40 miles, with the present equipment.”

While the assumption that doubling operating frequency would quadruple the range might be subject to question, the report does indicate rather clearly that the maximum transmission range was limited to about 10 miles, or the distance from Brant Rock to the receive site.

The report’s author speculates that if sufficient improvements (frequency and depth of modulation) could be made, the transmitting distance might be improved.

“Probably with the apparatus I saw in operation worked to its maximum efficiency, a range of about 100 miles might be reached, preserving commercial transmission.”

Alternator problems and limitations

I discovered some fairly extensive communication records between Fessenden and employees of the General Electric Company, manufacturers of the high-frequency alternators. One of these sheds some light on the problems with bringing the Brant Rock machine up to speed and full power on Dec. 21. It’s dated Dec. 7, 1906, and was written by Fessenden to Mr. H.G. Reist at GE. It indicates that his alternator was indeed hobbled.

“We managed to patch up one armature out of the different armatures sent us and have been using it to telephone from here to Plymouth. We get very good results and we have also completed a telephone relay which works very satisfactory [sic] we expect to make some tests shortly in telephoning from here to New York, part of the way by wireless and part by wire.

The present range of 50,000 cycles seems to be about fifty miles. If we can raise this frequency to 100,000 cycles the range will be about 200 miles.”

This is in line with the telco engineering report. Also, as the date of the letter is only two weeks prior to the demonstration, it has to be assumed that the problems (loss of power output with frequency) were not resolved by the demo date.

An earlier communication (Sept. 19, 1906) between Fessenden and D.C. Haskins at General Electric finds Fessenden complaining that the best output he can get from the alternator when operated above 30 kHz is less than 50 watts. This tracks closely with the 36 watts in the Bell Telephone report.

This 1906 power limitation and Fessenden’s stated maximum transmission distance of 50 miles cast substantial doubt on claims of reception from Norfolk and the West Indies.

Amplifying this is a passage from John V.L. Hogan’s 1923 book, “The Outline of Radio.”

“It is well known, however, that in 1906, Fessenden gave numerous practical demonstrations of radio-telephony between his experimental stations at Brant Rock and Plymouth, Massachusetts, and that in 1907 he increased his range from this distance of about twelve miles to such an extent that Brant Rock was able to communicate with New York, nearly two hundred miles away, and Washington, about five hundred miles.”

Hogan was a well-respected radio engineer and a former Fessenden employee.

While he may be slightly off base with his estimate of the distance to Washington, he does fix 1907 as the year for increased alternator power (and range) for Fessenden’s transmissions.

This is backed up further by later correspondence between Fessenden and General Electric about the delivery of more powerful and higher frequency alternators in 1907 and beyond.

Another document recently discovered provides more evidence of Fessenden’s transmission range limitations. This comes from Fessenden’s critique of a radio engineering book penned by British author, Dr. J. Erskins-Murray. The letter is dated May 27, 1907. While disputing and correcting some of the book’s chapters, Fessenden provides information on the capabilities of his radiotelephone transmitter.

“You may be interested to know that I am now fixing up apparatus for telephoning between Boston and Washington, a distance of 400 miles.”

The implication is that in mid-1907, he was still unable to reach this distance.

Even two years later, as 1909 drew to a close, radiotelephony over long distances was evasive enough to warrant a story in the New York Times. One of Fessenden’s backers, Hay Walker Jr., declared then in a special interview that Fessenden had just broken the 200 mile barrier. (Actually the report, dated Dec. 22, mentioned that Fessenden was doing even better then, with reception of his signals logged a few days earlier in Omaha.)

Physical facts

Letter dated Dec. 23, 1946 from James C. Armor to George Clark. Armor was a NESCO employee who was working at the company’s Machrihanish, Scotland wireless station in 1906. He recalls visiting Fessenden’s Brant Rock station on or about Christmas Eve 1906 and seeing the HF alternator, but nothing about any plans for a general broadcast.

Early in the 20th century, any improvement in a radio signal’s range had to be done at the transmitting side of things, as prior to de Forest’s triode, radio receivers were all essentially unamplified diode detectors. The best of these in use at the end of 1906 were based on Fessenden’s electrolytic detector. De Forest’s amplifier would not be available until 1907. At the time of the “broadcasts,” a radio receiver was nothing more than a tuned circuit, a detector and a pair of headphones.

Fessenden’s transmitting antenna also needs to be examined. It was a 420-feet insulated base vertical radiator with some top loading added.

The telco engineering report shows that in late 1906, Fessenden was transmitting at 50 kHz. That wavelength is nearly 20,000 feet, close to four miles. A quarter wavelength is around 5,000 feet, or more than 10 times the length of Fessenden’s antenna. A 420-foot antenna at 50 kHz is about 1/47 of a wavelength.

Even with top loading, questions have to be raised about efficiency. To put things in perspective, this is the equivalent of a station transmitting on 700 kHz with a 30-foot stub!

While Fessenden was well ahead of his time in using a series-fed vertical radiator, there’s no evidence that he employed our present-day system for grounding with multiple buried radial conductors. His ground system probably consisted of several rods tied together.

The primary mode for propagation of radio waves in the long-wave portion of the spectrum is ground wave. Even across seawater, published losses at 50 kHz are 56 dB at 500 miles and 62 dB at 1,000 miles.

Readers are left to speculate on the amount of signal that could have reached receivers at great distances from Fessenden’s 12 watt transmitter. Speculation also is necessary as to the ability of an unamplified detector to create a useful output from such a miniscule and poorly modulated amount of RF.

Please note that anyone who has experimented with radio knows that propagation miracles can and do occur. I’ve certainly experienced my share. However, it stretches the imagination to believe that “lightning” could strike twice exactly one week apart for Fessenden (Christmas and New Year’s Eve).

What may have happened

My 2006 article became a topic of conversation in some Internet chat rooms, and I was directed to one particular posting by RW reader Dan Hughes.

R.R. King had located stories from several December 1909 newspapers describing an extensive long-distance radio communication test planned that month between Fessenden’s Brant Rock station and U.S. naval vessels. Ships were to travel down the U.S. East Coast, on to the West Indies, Northern Africa and other distant points. Hampton Roads, Va., was listed as one stopover, as was Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

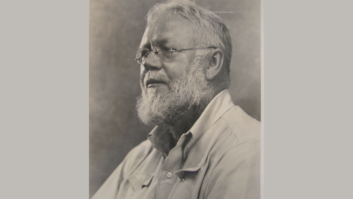

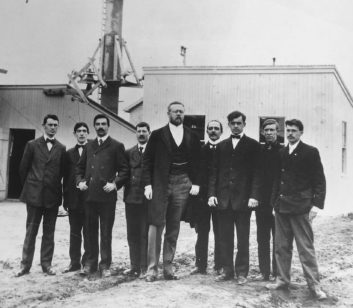

Reginald A. Fessenden posed with his employees at the Brant Rock radio facility. The base of the facility’s 420-foot insulated base vertical radiator is visible behind the group. Photo courtesy of the North Carolina State Archives

The object was to stay in radio contact as much as possible. While the tests would primarily involve radiotelegraphy, the Navy had been keenly interested in radiotelephony for at least a couple of years, keeping tabs on the work of von Arco, de Forest and Fessenden.

By 1909, Fessenden had a much more powerful alternator. Also, while not strictly a commercial device then, de Forest’s triode was available for purchase, and many radio operators were experimenting with it. This combination could make the transmission of speech and music over extended distances feasible.

Is it just possible that Fessenden, with his larger alternator, decided to do something “special” for Navy radio operators involved in the testing that Christmas Eve and got feedback from those near Newport, Va. (Hampton Roads), and a week later got verification from others at Guantanamo Bay (West Indies)? The Dec. 22 news story cited above mentions that Fessenden had been experimenting “over water” with two naval vessels operating “in West Indian waters.”)

By the end of 1909, radiotelephony no longer had much of a “wow” factor, as others besides Fessenden had been transmitting speech and music for some time. Most wireless operators had been exposed to radiotelephone transmissions, or at least were aware they were possible. This could well account for the absence of published notices of holiday broadcasts.

There is some amount of evidence that Fessenden, like a lot of us, didn’t have a particularly good memory when it came to recalling names and dates after several years. And, by the time Kintner’s 1932 letter arrived, Fessenden had had more than his share of emotional and physical jolts. Taking this into consideration, it’s understandable that he might have been steered by Kintner into claiming that special broadcasts were done in 1906, when they actually took place three years later.

In the aftermath of my 2006 Fessenden article, I was accused of trying to prove a negative after 100 years. I would readily agree that categorically proving Fessenden’s broadcasting claims were false is a near impossibility after a century; but in examining the facts at hand, it’s also equally difficult to prove a positive.

It is clear that he could have taken to the airwaves on the evening of Dec. 24, 1906; he demonstrated three days earlier that he had equipment for doing so.

The fact that speech and music were transmitted on Dec. 21, albeit a distance of only a few miles, could qualify Fessenden as the world’s first broadcaster. His signal was not encrypted, nor was it directed into a narrow point-to-point beam that could only be intercepted at Fessenden’s receive site. Anyone within range possessing an AM receiver could have listened in.

In fact, in his 1932 letter to Kintner, Fessenden comments on this in a rather ambivalent way:

“If you mean by broadcasting the transmission of speech, music and signing to other stations of the same ownership as the transmitter, then the [Dec. 21] program given to Dr. Kennelly, Prof. Elihu Thompson, the engineers of the Western Electric and A.T. &T. and other companies … would be a broadcast, as indeed would be the exhibitions of wireless telephony between Washington and Annapolis in 1903, and 1905.

“If, however, you do not call this a broadcast, then the program sent out Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve, 1906 would be the first broadcast.”

What exactly constitutes a broadcast still remains a matter of semantics and is open to debate.

The question mark that does exist in all of this falls squarely over the claimed Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve events. Despite a substantial amount of time spent near the 50th anniversary of those events, researchers could find nothing of substance to bolster Fessenden’s claim; and this was at a time when a number of individuals who could have had firsthand knowledge of the “broadcasts” were still walking the earth.

An extensive and continuing search by this writer 50 years later also has produced little tangible evidence to back up the claims in Fessenden’s 1932 letter.

It is my belief that while this case will never be “closed” with certainty, due to the amount and nature of counter evidence unearthed, any future references to the Dec. 24 and Dec. 31, 1906 broadcasts must be done with a certain degree of qualification.

Reginald Fessenden’s abilities as a scientist and an engineer are undeniable. He was first rate; a person very much ahead of his time. He single-handedly lifted radio science out of the spark or “whipcrack” era and into one of continuous wave technology. He was an incredible thinker and his work changed the very complexion of radio communication. We are all indebted to Fessenden for the wealth of scientific accomplishments produced during his 65 years of life.

In examining the “handout” that Fessenden provided attendees at his Dec. 21, 1906 technology demonstration, it’s evident that he was trying then to sell the telephone company on the idea of expanding service with his radiotelephone system. But he also made a strangely prophetic statement concerning another use for his invention:

“Telephony is admirably adapted for transmitting news, stock quotations, music, race reports, etc. simultaneously over a city, on account of the fact that no wires are needed and a single apparatus can distribute to ten thousand subscribers as easily as to a few. It is proposed to erect stations for this purpose in the large cities here and abroad.”

With a perspective of more than 100 years since these words were written, one is inclined to wonder what would have happened if Fessenden had focused on just this one plan. Perhaps listeners wouldn’t have had to wait another 15 years for radio to enter the home.

James E. O’Neal is a retired broadcast engineer with nearly four decades of experience in radio and television broadcasting. He began a post-retirement career in 2005 as technology editor for RW’s sister publication, TV Technology. He holds both commercial and amateur radio licenses; he is a life member of the Society of Broadcast Engineers and a member of the IEEE and SMPTE, serving on the board of editors of the latter. He is the author of a number of articles on broadcasting history that have appeared in Radio World and other publications.