We’ve all done it: Facing a situation with some exigency, we do something temporary to get things going again. Our intention is to come back after the crisis is over and apply a proper fix, but life and work gets in the way and we are delayed … or forget about it … or both.

That one little incident, by itself, is no big deal. The fix may not be neat, but it works, and it doesn’t really compromise the integrity of the facility or its infrastructure.

The trouble is, it happens again. And again. Busy engineers responsible for multiple stations with limited resources are under a lot of time pressure. As we apply quick fixes, we relieve the immediate pressure but cumulatively produce a whole new kind of pressure.

HANDS-ON WORK

For the past 20 years, I have mostly flown a desk, working at the corporate level and dealing with all the technical and physical plant administrative aspects of the company for which I work; but from time to time, I just have to get out in the field. It’s in the blood.

On several occasions, I have helped out with various projects and fixes at our studios and transmitter sites. Two sites in particular have vexed me with many layers of “quick fixes” for which permanent solutions were never applied.

Earlier this year, I helped out with transmitter replacements at these sites, and I took the opportunity to overhaul the RF plumbing and wiring infrastructure there, clearing layers of quick fixes and shortcuts that had piled up over the years.

For starters, the RF plumbing at one site was done with big loops of 7/8-inch Heliax that extended up from the transmitters to the ceiling grid, sometimes pressing tiles out of place before looping back down to the phasor.

It’s one of those things that we always meant to redo but never got around to. That was now job #1, and we did it up right. The site today is plumbed with shiny 1-5/8-inch rigid, and the big Heliax loops are gone.

Beyond that, we started picking our way through the AC and remote control wiring at the sites, and as we plowed through the transmitter replacements, I occasionally had to shake my head at the things I found. For example, tracing out the audio input wire from the aux transmitter, I found its end stripped and twisted together with two other wires, one for left and one for right, coming out of a distribution amplifier downstream of the analog outputs of the audio processor.

That cobbled-together L+R summing junction worked, but it wasn’t even soldered … and it was in no way insulated — just bare wires hanging deep in the rack. It’s a miracle that it hadn’t shorted out on an equipment chassis and produced an intermittent that would have driven our engineers crazy! I have no idea who was responsible for that “quick fix” but I certainly was glad to get rid of it.

POOR DOCUMENTATION

I found all sorts of other issues, many of them related to grounding, including one distribution panel that had no neutral — the 120 VAC circuits were getting their neutral from the ground in the box, which was only provided through the conduit itself.

The biggest irritation about these sites, however, was that there was no documentation on the remote control wiring scheme. I have no doubt that the very capable chief engineer who installed the wiring did in fact carefully document it, but over the years, that documentation was lost, probably as a result of computer upgrades and replacements. But whatever reason, there were no hard copies to be found at the sites — or anywhere.

As a result, anytime problem arose, the current CE had to spend a good bit of time to trace things out and find the cause. It was proof of the old adage that “a stitch in time saves nine.” Taking the time to do things right, document the changes and make sure that documentation is readily available will pay big dividends going forward.

And so it was that we stripped everything down to the bare bones and, with yellow legal pad in hand, started tracing out and documenting the wiring. It was a painstaking process, but as we moved along, we began to see how the underlying infrastructure was all very systematic, symmetrical and sensible.

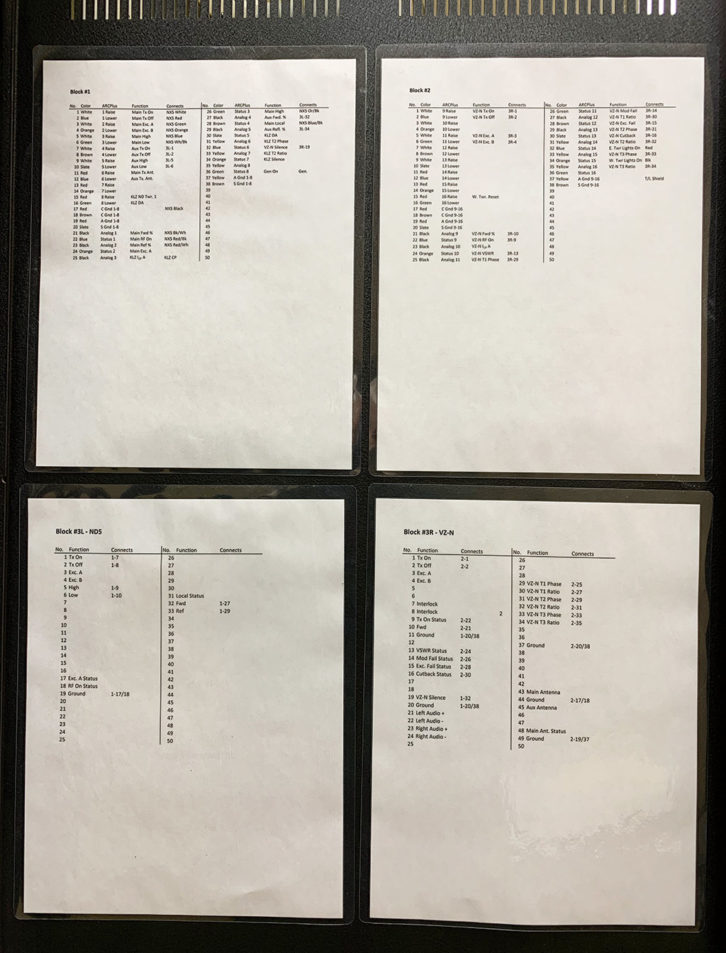

The command, status and metering connections from the remote control system were terminated on a split insulation displacement block. Similarly, the command, status and metering wiring from the transmitters also terminated on a split block. Since the main would become the aux and a new transmitter would become the main, we had to pull all the cross-connects anyway, so this really was the ideal time to make things right and produce new documentation.

In the end, it really didn’t take all that long. With the pages from the legal pad in hand, we made a spreadsheet with tabs for command, status and metering, showing wire numbers, wire color, function and cross-connect source/destination on each line. All those spreadsheets were printed out, laminated and affixed to the inside of the rack door for easy reference. Then it was simply a matter of making all the cross-connects and testing everything out.

Those laminated spreadsheets will have to be updated from time to time as changes are made, but at the very least they provide documentation of the underlying wiring scheme. To find channel 6-raise, for example, it’s a simple matter of finding that function on the command spreadsheet, identifying the wire number and getting the wire color for confirmation. In seconds, we know on exactly which terminal that function is punched. And that’s the way it ought to be.

CAN’T AFFORD TO LET IT PASS

We are engineers. Ask most anyone for a list of characteristics of an engineer and among them will be neatness, precision and organization. And those words are accurate, or they should be.

Certainly, there are some in our ranks who are a little challenged in those attributes, but for the most part, a good engineer wants to see things done neatly, with precision and organization. Yet, again, sometimes the exigencies get in the way and we’re tempted to take the shortcut.

I’ve heard it said that if you have time to do something twice, you have time to do it right. I would agree with that sentiment. Quite often, the reality is that it takes a lot less time to do a task right the first time than it does to apply a quick fix now and make it right later. So look at it this way: By doing it right the first time, you’ll actually save time, and those who come after you will benefit as well.

While he’s not an engineer, singer/songwriter Billy Joel captured the sentiment well:

I’ve gotta get it right the first time

That’s the main thing,

I can’t afford to let it pass

You get it right the next time that’s not the same thing,

Gonna have to make the first time last

Enough said.

Cris Alexander, CPBE AMD DRB, is director of engineering of Crawford Broadcasting Co. and technical editor of RW Engineering Extra. Email him your thoughts and suggestions for articles to [email protected].