The author is project manager, radio, on the Technology and Innovation team of the European Broadcasting Union, an alliance of public service media with 115 member organizations in 56 countries.

For almost as long as radio and television services have existed, a large amount of effort has been expended on measuring the audiences that listen to them.

Largely driven by the boom in U.S. commercial broadcasting in the 1930s, measurements were necessary to define the advertising models that were to sustain these new services.

Although audience measurement on television would come to dominate what is understood to be “listening figures,” audience measurement is still a vital part of radio both for commercial and public service broadcasters.

In Europe, methods of audience measurement for radio vary between countries, but three methods have been generally adopted across industry: diaries, interviews and electronic measurement.

These give periodic snapshots of listening (e.g. ranging from daily to twice yearly), which does not give a clear picture of individual usage, either being driven purely from device usage, or being more based off brand recall, as such providing a broader picture of performance.

More detailed information about real engagement with specific programs, special events, segments and topics is lost in the aggregation. An experienced manager will know that a good radio station is the sum of all these parts yet relies on “craft” that can sometimes be hard to justify to those who control budgets.

An alternative arrived in the 1990s with the rise of online measurement. This introduced a number of new metrics but also provided analytic data that could be available instantly.

Thus, those publishing on the web could have a live view of how audiences were reacting to their content. For newspaper publishers, this has fundamentally changed their business; and although this has led to a rise in “clickbait,” it is notable that audiences still place value in “trusted sources.”

Audience measurement for radio services has been changing in similar ways with the rise of internet streaming and connected devices. Being able to measure how many people are listening to a stream, during what times and for how long can, in theory, give us the analogy to traditional measurement, with the benefit of being near-instantaneous.

Broadcasters have been trying this for the best part of two decades, although currently largely only for internal use. The reason is that much of this data relies on inference from server logs, by using proprietary methods from the broadcaster’s own applications or through third-party applications. A lack of shared technical standards and methodologies has limited development.

By contrast, traditional methods may not be sophisticated or granular but they have the advantage that they have been accepted as valid and largely transparent. Additionally, the different actors that sit between a broadcaster and their listeners can obfuscate the situation, resulting in the broadcaster not getting the full picture.

With a distribution chain that now includes increasing number of layers, each with opportunities for aggregation and caching, numbers are harder to rely on. For newer connected platforms like smart speakers, acquiring comparable figures can be challenging both for live and on-demand listening and again reliant on the platform (e.g. Amazon, Google) granting access. Importantly, the only party with access to the whole picture is the platform provider itself.

While internet streaming for radio has previously been a minority proportion of overall listening, dwarfed by use of broadcast, this will perhaps change as audiences consume more on-demand and personalized content, as well as with the further rollout of connected cars.

A clearer view of consumption across all platforms will become more and more important. Having a standardized method that can directly carry analytics for both broadcast and broadband, live and on-demand — the full spectrum of hybrid radio — is needed.

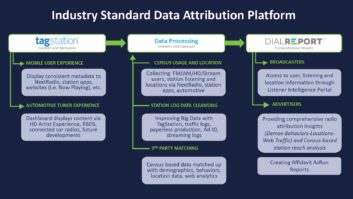

Such an effort has started as a collaboration among several organizations, led by the RadioDNS Technical Group, which I chair. The body is responsible for developing and maintaining open standards for hybrid radio, involving representatives from broadcasters and associations across three continents (including the National Association of Broadcasters and the European Broadcasting Union) as well as device manufacturers and service providers.

The goal of the project is to develop a free and open standard for the gathering of analytic data from the connected devices themselves, as well as the definition of a basic set of data to be gathered. By optionally using RadioDNS Hybrid Lookup, the broadcaster can define and control where the data is sent regardless of whether the listening is happening over broadcast or broadband.

Having the ability to determine how a listener moves between platforms (e.g. FM and IP), the broadcaster’s own radio services and live/on-demand during a session, in an anonymized way, is key to revealing the real value of hybrid radio services.

This can act as proof to broadcasters of their value, in a way that supports future investment. This benefits device manufacturers, increasing the coverage and quality of hybrid radio services that can be offered free-to-access for their own customers.

Ultimately, the winner will be the listener. Regardless of the means and mode of listening, enabling measurability for the connected era can improve radio, keeping it vibrant and exciting in an increasingly competitive space.