It’s a great day when you find a product designed for another industry that can be used productively in broadcast applications. Power-All Power Grip pedal board tape, provided by Godlyke Distributing, is one.

The original idea came about because musicians were using hook-and-loop fastening tape to secure guitar pedals to wooden boards. The adhesive would give up, and the pedals on the boards would fall off.

Power-Grip is simple and ingenious. Pieces of the tape mate to itself via rows of mushroom-shaped posts that form a much stronger bond than traditional hook-and-loop fasteners do. Plus, when its adhesive backing cures to the surface to which it is affixed, it’s not going anywhere.

The tape is sold in 1 meter (39.37-inch) by 1-inch rolls, and can be ordered online for $14.95. On the website is a video that demonstrates the installation and results; see www.godlyke.com under the Power-Grip pull-down.

So where can this be used around the station?

How about to secure that copy stand atop the console? The stand can be removed to get inside the board; otherwise it stays put. Or secure remote equipment accessories like power supplies to the sides of their respective units.

Wherever you need a strong bond, Power-Grip tape will work. Keep in mind that the adhesive backing is very strong and may remove paint from the surface when the time comes to pull it up.

* * *

Fig. 1: A rat’s nest like this might scare anyone off.

Most engineers look forward to doing a studio reconstruction project at least once in their careers.

Phillip Vaughan dropped off “before and after” pictures. He says Fig. 1 is representative of wiring at the facility, so you know he had his work cut out for him.

“It’s amazing how bad the wiring can get around a station over the years,” he says. One quick “temporary” wire here and there — well, we’ve all seen it. Phillip found himself approaching any work on the studio blocks with trepidation, afraid he might take the studio down.

Tired of the situation, he drew up plans to rewire them. A complete overhaul would have been better, but this was the next best thing.

Phillip was joined by two other engineers; they finished the studio wiring in one weekend, while the station broadcast from the backup air studio. Fig. 2 shows the result.

On another note, Phillip has noticed that about every piece of broadcast equipment built these days has a Web interface. Some of his monitoring equipment can give readings only through that interface; there’s nothing on the front panel.

Fig. 2: Three engineers knocked the job out in a weekend.

Personally, he would rather be able to just look at the front of a piece of equipment to get the info he needs from it. What do you think? Would you pay a little more for equipment that provides traditional front-panel metering, status and control?

* * *

Guy Berry, manager at Potomac Instruments, writes with a couple of cautions.

In this day of doing more with less, we may be tempted to skimp on test instrument calibrations. If you decide to use a calibration service not provided by the manufacturer, check it out. A bargain-basement calibration price may come back to bite you if the instrument is not accurate.

In the case of field intensity measurements, the cost could be enormous. This is not to say you should avoid non-manufacturer calibration services; there are a number of qualified services.

However, exercise due diligence. Speak to engineers who have used the service. Determine the company’s procedures and how they compare to those of the manufacturer.

Guy’s caution is that anyone can twist a knob. Know what you are paying for!

His other nugget, especially for engineers maintaining older equipment, is to check the manufacturer’s website for manuals and application notes before looking elsewhere. He points out that $15 or $20 sounds like a fair price for a manual offered by a third party — until you find out the manual is offered by the manufacturer for free.

As for Potomac Instruments, Guy reports the company has settled nicely into its new home in Frederick, Md. The building used to be the home of Bradley Broadcast, which is now a division of SCMS.

What makes Potomac’s move especially noteworthy is that for the first time in some 40 years, production is located on one single floor, so product no longer needs to be carried up and down stairs.

* * *

From across the Pacific, Paul Sagi from Kuala Lumpur comments on our story in Radio World’s May 4 edition. (You can find recent articles at radioworld.com under Columns; click on Workbench. The article is headlined “Get to Know That New EAS Box>.”)

Paul writes that 1N4001 diodes are made for power frequency use. He feels their junction turn-off time may be a bit slow for audio use, thus with audio circuits Paul chooses 1N914 diodes.

The column also mentions a 4.7 uF 50V non-polarized capacitor. Paul writes that sometimes, non-polarized electrolytic capacitors are difficult to obtain; regular polarized electrolytic capacitors can be used instead.

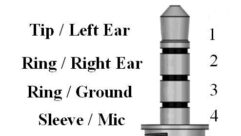

Fig. 3: Green trumps white in one reader’s choice of connector.

Here’s what you do. To use ordinary polarized capacitors in place of the 4.7 uF capacitor, simply connect the negative leads of two 10 uF 25V capacitors to each other (putting the capacitors in series to halve the capacitance). Solder the two positive leads into the circuit, and the problem is solved.

Paul had some experience with the white barrier terminal connector shown in the article photo, reproduced here in Fig. 3. It works; but the popular green Phoenix connector, also seen in the photo, is better.

That’s because the screws of the white connector rub against the wire as they are tightened and may break or weaken the wire, leading to later failure, especially in mobile applications. The Phoenix connector, on the other hand, clamps the wire without rubbing against it, hence Paul’s preference.

Contribute to Workbench! You’ll help your fellow engineers, and qualify for SBE recertification credit. Send Workbench tips to [email protected]. Fax to (603) 472-4944.

Author John Bisset has spent 43 years in the broadcasting industry, and is still learning. He works for Tieline Technology, is SBE certified and is a past recipient of the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award.