How true is the adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same. That certainly seems to be the case in comparing the tumult and upheaval of the late 1960s to the tumult and upheaval of 2020 — when groups of impassioned young people decide to stand up for the rights of the unheard, to fight for justice for the underrepresented, to make a difference in their community.

How true is the adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same. That certainly seems to be the case in comparing the tumult and upheaval of the late 1960s to the tumult and upheaval of 2020 — when groups of impassioned young people decide to stand up for the rights of the unheard, to fight for justice for the underrepresented, to make a difference in their community.

But 60 years ago, without the buzz of social media to distract and divert, one medium regularly played a starring role in clarifying the noise and commotion of the late 1960s.

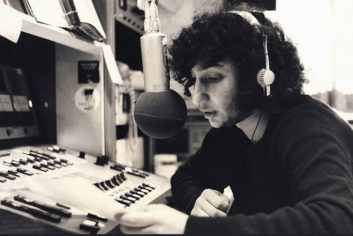

For the city of Boston, station WBCN(FM) was that place. Going on-air on analog 104.1 MHz in 1968, this community broadcaster became ground zero for passionate, talented, community-minded young people looking for like-minded voices willing to fight for civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights and against the use of police force at their city. Every caller, every staffer, every volunteer was met with the same mantra: At WBCN, you have a voice.

“The mission of the station was that every listener was important,” said Bill Lichtenstein, a former newscaster at WBCN and now a documentary filmmaker.

A long way away from the corporate-run morass of indistinguishable stations (which listeners here in 2020 often rail against) WBCN was a progressive rock station where the station’s DJs had latitude on the music they played and the causes they championed.

“There was just an intuitive sense during that period this [station] was an important place to be,” Lichtenstein said. “[It seemed that] almost anybody of note politically, socially, culturally, musically was there. If you crossed paths with Boston, you crossed path with WBCN.”

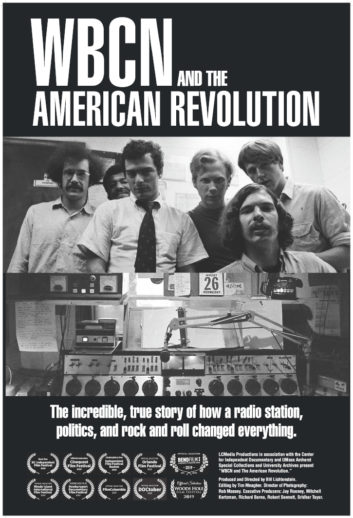

Last year, the station and its impact on the community was memorialized in the award-winning documentary “WBCN and The American Revolution.” After a successful run on the film festival circuit, the film is being made available as a digital rental in partnership with the National Federation of Community Broadcasters (NFCB) and radio and film organizations across the country, giving voice once again to a radio station that was willing to stand up and call for change.

“WBCN came to our attention [in regard to a] panel about community radios past, present and future,” said Ernesto Aguilar, the program director at the NFCB. “It was a beautiful and compelling story about a unique time in history.” Soon after Aguilar and Lichtenstein struck up a conversation about helping modern stations link into that history and draw parallels for what we’re seeing today. “And to remind people that radio connects into a point in our imagination,” Aguilar said. “Radio has this very special place in people’s hearts.”

Soon after it opened its doors, the new WBCN began to find its voice.

It supported alternative news coverage and underground investigative reporting, airing live concerts and covering novel topics like the hazards of street drugs. The station engendered legendary music industry stories too, like airing the first interview of a young Bruce Springsteen or snagging bootleg recordings from major artists such as The Beatles.

“Radio was really the access point to rock and roll and youth culture,” said Lichtenstein, who found a part-time job at the station when he was 14.

Even after the station evolved from the underground/progressive format of the 1960s to more mainstream album rock later on, DJs on WBCN still had relative control over the music they played and the conversations they started. The result was a varied mix of rock music peppered in with local music and the introduction of new acts like The Cars, The Ramones, The Clash and The Police. One day you might hear an interview with Jerry Garcia. The next you might hear a live performance by Patti Smith.

Through it all, WBCN became a beloved institution in Boston because it affirmed the idea that if you speak out, you can change things.

“I can’t think of any other cultural institution that [makes] people just melt [other than radio,]” Lichtenstein said. “There was such an affection for that station. There was this idea that you can speak out and change things. That media can change the world.”

For Lichtenstein, the idea to create a retrospective on the station was 50 years in the making. In an interview with the Boston Herald in 2006, Lichtenstein asked for readers to contact him if they had tapes of broadcasts, photos and other documents from WBCN. Material started pouring in, an influx of fossilized remains of tape and photos that chronicled the life of the station. Many of those moments that might have been lost to the ages were actually be out there, Lichtenstein said, held on to by fans, former DJs and hidden in the station’s back rooms. All in all, more than 100,000 audio and visual items were donated to the project including never-before-exhibited film clips by Andy Warhol and memorable air check segments from on-air moments.

The documentary is now serving to start a conversation with community radio stations, to help them link into that 1960s history and draw parallels for what we’re seeing today.

It also makes clear how difficult things were in certain areas, Lichtenstein said. “Women were verboten to be on the radio or have a broadcast job. And it took courageous steps to shatter that wall. So how you go about creating change?”

“Radio continues to serve an important role in that process,” he said. “It has a way of bringing people together that’s different from TV or print.”

What stood out to Aguilar about the documentary was that it showcased a station that was offering listeners in 1968 something they wouldn’t ordinarily hear or experience. There are also are obvious parallels to what’s happening today, he said. “[Radio is still] able to tap into people’s disaffection. To remind everyone that as a whole, we can come together about things we want to have a conversation about. Radio is never is going to go away as long as people want to have conversations,” Aguilar said.

According to Lichtenstein and the NFCB, the film has been successfully used as a fundraising platform by stations in up and down the East and West Coasts. Ultimately, Lichtenstein and the NFCB hope to support many more stations with this campaign.

Documentaries like this one are key to the work the NFCB is doing, Aguilar said. “What we’re seeing right now — with so many fluctuations in media, lots of layoffs and the FCC changing the main studio rule — is that these smaller organization depend on a variety of people in their communities to provide radio programming.”

When theaters around the country began closing one after another due to the pandemic, one of Lichtenstein’s first thoughts was to reach out to radio stations with this documentary.

“I do think public radio in a way is largely driven by national programs, agenda, discussions,” he said. “To me the tradition of WBCN lives on most in these communities.”

Screenings of the WBNC documentary “WBCN and the American Revolution” are ongoing. Public stations interested in participating in a screening of the film can contact Eliza Licht and Alice Quinlan of the film’s community outreach team at screenthefilm.com or [email protected].