This article originally appeared in the May 23, 2012 issue of Radio World.

John Hibbett DeWitt Jr. was a radio wunderkind.

He put Nashville’s first radio station on the air when he was 16; was hired by Bell Labs even though he was a college dropout; revolutionized AM transmitter technology; built the country’s first commercial FM station; set the stage for satellite communications; put Nashville’s first TV station on the air; created the first solid-state broadcast gear; and headed operations for one of the nation’s biggest entertainment operations.

Yet Jack DeWitt seems to have escaped notice in many industry circles, even though he left the transmitter building for the last time only about 13 years ago.

Beginnings

DeWitt was born in Tennessee on Feb. 20, 1906, about the time serious experimentation in transmitting speech and music over the air began. He became interested in radio early; he was a radio amateur operator in his early teens and was hired at age 16 to construct a radio station for a Nashville girls’ school. The callsign WDAA was issued in 1922 to what became the city’s first commercially licensed station.

Before completing high school, DeWitt started up two other Nashville stations. After graduation, he briefly explored a career as a shipboard radio operator but decided this was not his calling and enrolled at Vanderbilt University. His career at the school proved equally short-lived, as did DeWitt’s next stop at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

“I became interested in a broadcasting station [in Knoxville] that was owned by a local telephone company and spent my time at it rather than studying,” DeWitt said, as quoted in Craig Havighurst’s 2007 book, “Air Castle of the South: WSM and the Making of Music City.”

DeWitt’s efforts to obtain a college degree ended here; but as the record shows, he didn’t really need one.

WSM Takes to the Air

When the 19-year-old returned to Nashville, he learned that the National Life and Accident Insurance Co. was interested in launching a radio station. He was hired to help and spent summer and fall working to construct what was to become WSM (“We Shield Millions,” a reference to the insurance company’s slogan). The station took to the air on the evening of Oct. 5, 1925, with DeWitt running the controls.

He remained at WSM for a time and did engineering work for other stations, until an opportunity to become more deeply involved in radio engineering arrived in 1928 with a visit to WSM by a Bell Labs engineer.

DeWitt made a favorable impression, and soon the Nashville radio prodigy was on his way to New York City and a research job at the prestigious laboratory.

However, it was not to last. In the fall of 1930 DeWitt took leave from that job to testify at Federal Radio Commission hearings aimed at determining WSM’s worthiness for one of the new 50 kW assignments opening up. WSM was awarded the coveted slot and DeWitt was offered the job of shepherding the power increase as the station’s chief engineer.

Understandably, this caused him considerable angst. “It was one of the tough decisions of my life,” he said, as recorded in Havighurst’s book.

“Here was the great Bell Telephone Laboratories, where I really got a good education in electronics with all sorts of facilities and everything. And here was WSM, a radio station in my hometown. Should I go back to my hometown where I would be a big frog on a little pond, or would I stay in New York and try to make my career?”

Return to Nashville

The pond won out, and soon DeWitt was back in his old surroundings, where the 50 kW project was in progress.

One element was not quite a done deal: the antenna. RCA, supplier of the 50 kW transmitter, advocated conventional flat-top horizontal antenna technology. DeWitt had been involved at Bell Labs in testing a “new” half-wave vertical radiator, and he appreciated the superiority of that design.

“Bell Laboratories was in the business of designing radio transmitters and studio equipment [and] now, they wanted a good antenna to recommend to purchasers of their equipment,” DeWitt recalled in a 1982 interview.

“There was a man by the name of Dr. Stuart Ballantine … brilliant man … He pointed out that there was no point in putting up separate towers and stringing antennas between them because the towers could only be a problem due to the currents induced in them from the antenna and it would distort the pattern. Why not use [just] the tower?

“The first one of those towers was put in at Wayne Township, N.J., for the Columbia Broadcasting System. Strangely enough, I worked on that installation.”

DeWitt didn’t have a tough job in selling the vertical, which added only about 10% to the $200,000 budgeted for the power increase. Blaw-Knox was awarded the contract for another “diamond” tower. It is still used by WSM.

After the plant went into service, DeWitt started experiments aimed at improving transmitter performance, earning him his first patent, a feedback system for reducing hum and noise.

“It reduced the distortion from maybe 5–8% percent in the transmitter, to about 1%, and it was broadband,” said DeWitt. “I got a patent on it and sold it to RCA for $10,000, which allowed me to build a house.”

Making History

A lifelong love of good music, coupled with curiosity and expertise in RF, undoubtedly were driving factors in DeWitt’s lobbying the insurance giant to apply for an experimental FM license. He designed and constructed a 20 kW transmitter for the purpose, along with a turnstile antenna that was mounted atop the AM radiator, apparently the first time that an AM tower served a dual purpose.

WSM was a pioneer FM broadcaster in another respect. In 1941 it was granted the country’s first commercial FM license, W47NV. The station’s ERP was 65 kW; it provided service as far away as Alabama and Kentucky. (The low-band station survived through the war years, moving to present day high-band operations in the late 1940s. Unfortunately, like many pioneer FM stations, it produced little revenue and went dark in the 1950s.)

With America’s entry into WWII in 1941, DeWitt’s electronics expertise was sought by the military’s radar program. He became director of the Army’s Evans Signal Laboratories in New Jersey and did much pioneering work in radar. But it was a postwar experiment that put him and the lab in the limelight.

DeWitt had a strong interest in space and astronomy, and after the war’s end, found time to recreate an experiment he’d tried unsuccessfully in 1939: bouncing radio signals from the moon.

He made this entry in his personal notebook in May of 1940:

It ha[d] occurred to me that it might be possible to reflect ultra-short waves from the moon. If this could be done it would open up wide possibilities for the study of the upper atmosphere. So far as I know no one has ever sent waves off the earth and measured their return through the entire atmosphere of the earth.

In addition, this may open up a new method of world communication.

The moon is visible several hours out of every 24-hour period in the year. There are many times when communication by this method might be extremely valuable such as during magnetic storms and daytime radio ‘blackouts.’ This may provide a means in the future of bringing television programs over long distances, such as across the oceans.”

In early 1946, his second moon bounce attempt succeeded, opening the door to the age of satellite communications. (While Arthur C. Clarke predicted satellite communications in a 1945 magazine article, it was DeWitt who actually relayed the first radio signal from a satellite, in this case, the moon.)

Peacetime Career

After the war, broadcasting was burgeoning, with equipment once again available for upgrading stations and constructing new ones. And while a partnership in a Washington engineering firm — Ring and Clark — looked especially promising, another offer soon surfaced.

The National Life folks had decided to separate WSM operations — along with those of the Grand Ole Opry, and the organization’s artist bureau — from the insurance business. It sought someone to head up these newly formed enterprises as president. DeWitt’s name was at the top of the list. Though tempted by the Washington job, he realized that he belonged back in Nashville.

Television was starting to come into its own, and just as with FM, DeWitt wanted to be first on the air in Nashville.

WSM managed to secure a CP before the FCC’s 1948 “freeze” on new applications; soon DeWitt was laying the groundwork for a new television station.

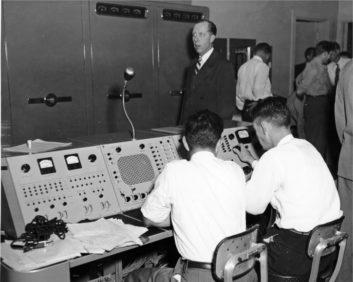

Television cameras were especially pricey in 1950, the year WSM(TV) took to the air. Few people had seen one. Yet DeWitt was bold enough to roll his own. According to Ray Tichenor, who was hired during WSM(TV)’s first year, DeWitt bought two RCA cameras and immediately cloned them.

“Of course, he had to buy the IO [image orthicon] tubes and yokes from RCA, but everything else was done in-house,” Tichenor recalled. “The copies worked as well as the originals. Mr. DeWitt was a genius at building things.”

Television transmitters have always been big-ticket items as well. As DeWitt was an RF man par excellence, he likely would have fabricated his own if time hadn’t been a factor, but DeWitt settled for a commercial rig. Once the dust settled, though, Nashville’s RF grandmaster constructed a backup 5 kW television transmitter, as well as a 20 kW linear amplifier for boosting ERP up to the 100 kW authorized by the FCC in 1952.

This “exciter/afterburner” combo remained in service for a quarter century or so. To the credit of DeWitt and his engineering staff, the workmanship was exacting. The one-of-a-kind rig offered scant evidence of being homebrewed, blending in perfectly with the commercial transmitter.

Solid-State Out of the Gate

DeWitt also should be recognized for beating the “Camden giant” — and apparently everyone else — in bringing solid-state broadcast gear to the marketplace.

This was via the “International Nuclear” equipment line. The company existed for some two decades and produced a range of broadcast gear, with its initial product being a transistorized video distribution amplifier (the TDA-2) designed by DeWitt.

Loyd Wayne Pilkinton, a former technician at International Nuclear, recalled that building broadcast gear was really not part of that company’s plan.

“International Nuclear Corp. was formed by Mr. Ray Weiland of Brentwood, Tenn.,” Pilkinton said. “Ray was working at Vanderbilt Hospital for Dr. George R. Meneely and had been building electronic equipment for the new age of nuclear medicine. I worked for Dr. Meneely and Ray at Vanderbilt Hospital during the day and for International Nuclear Corp. at night and Saturdays. I wired the first 2,000 TDA-2 units.”

DeWitt filed for a patent in 1961. It became one of the first patents for solid-state broadcast products.

WSM (We Shall Manufacture)

Homebrewing was done on a grand scale at WSM. As explained by J. Wayne Caluger, the TV director of engineering in the years after DeWitt’s 1968 retirement, it was easier in the 1950s and ’60s for station personnel to build equipment than to buy it.

WSM had a small capital equipment budget but a large maintenance fund. Thanks to DeWitt’s design engineering ability, technicians with excellent construction skills and a Nashville metal fabricator that could match most anyone’s layout and paint job, the station had incentive to brew its own. Employees joked that the WSM call sign really stood for “We Shall Manufacture.”

This do-it-yourself modality served WSM well and provided technicians the opportunity to learn about inner workings of equipment they used on a daily basis.

On one occasion after DeWitt’s retirement, this mentality caused a glitch. During a visit to the station he noticed a large number of “bootlegged” International Nuclear distribution amps. DeWitt, who received design royalties from International Nuclear, became upset.

“He went in and complained … about how this was costing him money,” said Caluger. “He was quickly reminded of all the reverse engineering that he’d done and was told that the pot couldn’t really call the kettle black.”

Other Accomplishments

DeWitt is also remembered by former WSM staffers for innovations such as a homebrewed system for receiving first-generation weather satellite images. By constructing it in-house, DeWitt trumped another Nashville station that had been promoting the arrival of satellite imagery, for a fraction of the cost of a commercial system.

He constructed an atomic frequency standard for maintaining WSM(AM) at 650 kHz. The carrier was so precise that other stations used it as a frequency standard.

After retirement, DeWitt kept experimenting and inventing in several fields, including optics and lasers, which led to a surveying instrument for civil engineers.

Jack DeWitt died on Jan. 25, 1999, some 53 years after his successful moon bounce experiment and just a few weeks shy of his 93rd birthday. A joint Senate/House resolution in the Tennessee legislature mourned his death “while also rejoicing in the life of this exceptional man whose exemplary character, many accomplishments in the realms of science and technology, and voluminous contributions to the growth and prosperity of this state and nation will be remembered and appreciated for generations to come.”

James O’Neal is technology editor of TV Technology magazine. He has written in Radio World about VOA’s Greenville, N.C., facility; the evolution of broadcast transmitter power supplies; radio pioneer Mary Day Lee; and numerous other topics.

He thanks David Hilliard of Wiley Rein LLP for recorded interviews and information about DeWitt’s involvement in the CCBS. Clyde Haehnele, retired WLW engineer, helped with DeWitt’s postwar work in Washington. Former WSM Director of Engineering J. Wayne Caluger provided personal recollections. Loyd Wayne Pilkinton and Larry Bearden offered insights about WSM and International Nuclear Corp. John Hettish maintains the WSM radio tower and provided photos of the FM turnstile radiator still mounted atop the AM tower. Craig Havighurst fielded many questions and helped with photos; his book “Air Castle of the South: WSM and the Making of Music City” is highly recommended. Thanks also to Scott Baxter, an RF genius put to work tending the homebrew WSM(TV) transmitter in his teenage years; Les Leverett, long-time National Life and Accident Insurance chief photographer; and the late Ray Tichenor, who was hired to work at the fledgling TV operation in 1950, shortly after high school, and remained with the operation for more than four decades. Before his passing, Mr. Tichenor provided useful information especially about the homebrew television cameras and the television transmitter.