The evening of Tuesday, Nov. 2, 1920, had come and gone. KDKA, 8MK, and perhaps others had taken to the airwaves that evening to report returns in the election that put Warren G. Harding in the White House. A few hundred, perhaps a few thousand people — there were no rating services then — managed to gain proximity to a primitive radio receiver of some sort and listened as the results were tallied and read into equally primitive microphones.

In retrospect, one can’t help but wonder what went through the minds of those individuals who stayed up late to present election results via “radiophone.” A radio broadcast is at best an intangible — something highly ephemeral, perhaps even a bit ethereal.

Had their voices really gone out into space to reach invisible ears? Had anything happened at all? There had to have been at least a slight sense of unreality in those first moments, a feeling perhaps best captured by Garrison Keillor in his description of the inaugural broadcast of mythical station WLT in St. Paul, Minn.

“Roy Jr. switched off the transmitter. It sighed, expelling a faint breath that smelled of vacuum tubes and electrodes. Ray leaned against the doorway, feeling faint. His speech had exhausted him.

‘Did anybody hear it, do you think?’

‘Guess so.’

‘Anybody ring up and say so?’

‘Nope. Maybe they were too busy listening.”

(WLT: A Radio Romance, 1992)

What now?

KDKA’s seminal broadcast way back in 1920, is now viewed as a great day — a truly historical one; something that changed the landscape forever. However, as with any event important enough to make its way into the history books, there’s always the dawning of the next day — the interval after the initial exuberance has passed and cold reality begins to set in. It is then that those who have been cheering in celebration are forced to stop and ponder “what happens next?”

This thought most certainly was on the minds of those at Westinghouse the morning of Wednesday, Nov.3, 1920.

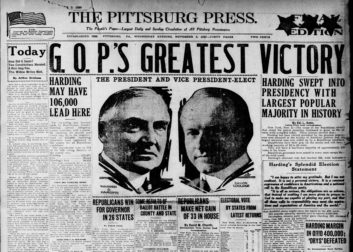

Newspaper headlines that day said virtually nothing about radio. Instead, they screamed “HARDING BY MILLIONS,” “G.O.P.’s GREATEST VICTORY,” “HARDING WINS,” or whatever similar messages regarding election outcomes that could be fitted across the page in the largest type fonts available.

The words “radio” or “wireless” were hard to find, even down in the “noise” of the 6-point type reserved for classifieds and obituaries. Was there really a future in radio, or was the broadcast destined to be just another “flash in the pan?

Where are the cards and letters?

Judging from initial reaction by the public — other than some amount of well-wishing by those tuning in the KDKA broadcast — nothing had really changed. An examination of post-election night periodicals seems to indicate there was little direct impact — no uptick in business at the few sources for radio receivers and parts, no immediate backlog of applications for new stations at the Department of Commerce.

The public continued to read their newspapers and magazines, exchange gossip at card games and in barber shops, and seek out sources of illicit alcohol as Prohibition set in. The print media for the most part ignored radio as 1920 flowed on into 1921.

This would not be unexpected, as there is generally a “wait and see” attitude following the launch of new technology. A commercial aviation industry did not spring up immediately after the Wright brothers’ inaugural flight, and more than 100 years passed between the issuance of a patent for the first dishwasher and its widespread appearance in homes.

As for “radio gripping the hearts and imagination of Americans everywhere” following KDKA’s big broadcast, there’s little evidence to indicate that it initially made much difference one way or the other.

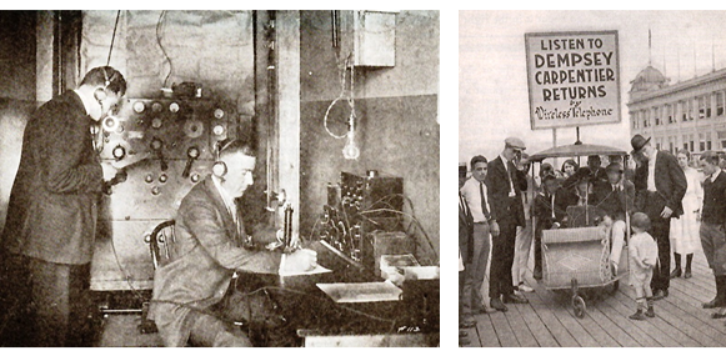

There were even non-believers and scoffers. One 1921 account describes an early demonstration of broadcasting with music transmissions demonstrated via a “mobile” receiver constructed in a baby carriage. Some “ear witnesses” were in denial of the wireless nature of what they were hearing, insisting that there must be a record player concealed in the carriage.

Pittsburgh push continues

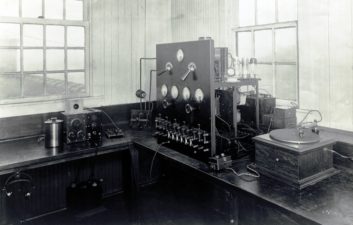

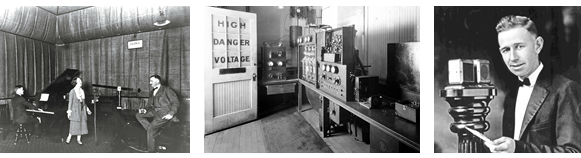

Westinghouse still convinced it was riding a winning horse, continued to plow money into fledgling KDKA in 1921, boosting its power from 100 watts to 500, and then a full kilowatt and creating a broadcast studio.

Program offerings were also expanded with the addition of live musical performances, agricultural and weather reports, church services, and more

Westinghouse’s PR branch stayed busy, issuing frequent press releases about KDKA to any and all print publications that might help to further the cause.

An example of such Westinghouse puffery appears the April 1921 issue of the trade publication, Radio News:

THEATRE MUSIC SENT BY RADIOFONE

The latest thing in providing entertainment by radiofone in Pittsburgh is the sending out of portions of the program given at a downtown theater. This is accomplisht in the same manner as the church services at the Calvary Church in the East End. Telefone transmitters placed in the theater collect and transmit the sound over a special telefone wire to the radio station of the Westinghouse company in East Pittsburgh (Radio KDKA), where it is then sent out by radiofone.

Promotions big and small

Hugo Gernsback, editor of Radio News, and something of a visionary and prophet, was also a believer in radio broadcasting’s future, going so far as to drop the word “Amateur” from the title of his radio magazine in mid-1920 and welcoming such press releases.

Throughout 1921 Gernsbeck advocated “radio for everyone” in his magazine’s pages, with sometimes lengthy articles on new “radiophone” stations, demonstrations of speech and music transmissions, and simplified and less expensive access to radio for the public.

Perhaps the biggest boost received by radio broadcasting during its first year was the July 2 “fight of the century” featuring Georges Carpentier and Jack Dempsey.

While radio coverage was not the prime objective of this heavily-promoted event, others, outside of Westinghouse (most-notably RCA’s David Sarnoff), apparently saw some dollar signs in the new medium and added it to the mix.

The fight coverage station, WJY, was licensed as a temporary entity, and equipped with a General Electric transmitter that had been sidelined from delivery to another customer. (The “borrowed” nature of the gear may explain why WJY operated at 1,600 meters (187 kHz.) Another twist was the recruiting of licensed radio amateurs to assist in disseminating the broadcast, as radio sets were not really household items in 1921.

The “ham” community set up receiving apparatus in performance halls and other venues, and ensured that everything worked properly. Even though reception of a 187 kHz signal and amplification to room-filling volume presented a challenge to the amateur radio ranks, many were able to deliver the goods to their captive and somewhat astonished audiences.

That collective audience was substantial, estimated at some 300,000, and most-assuredly exceeded “tuners-in” to KDKA’s election night event.

While the intent of July broadcast was to attract attention to the fight, it also did much to arouse public interest in radio, perhaps even more so than what Westinghouse was trying to accomplish with KDKA.

Priming the pump

1921 also saw other, less flamboyant, demonstrations of broadcasting.

Perhaps the best documented of these took place on Nov. 15, 1921 in Pine Bluff, Ark., where the president of the Arkansas Power and Light Company, Harvey Couch, had arranged for a broadcast of live and recorded music from Couch’s home to a meeting of the city’s Rotary Club. (AP&L was a Westinghouse customer, with Couch touring the KDKA operation during a buying trip to Pittsburgh and becoming a convert.)

Couch, the Rotarians, and others were so impressed with this latest miracle of science that shortly after the pre-Thanksgiving demo, Couch applied for a license for Arkansas’s first broadcast station.

This, and similar efforts around the country had the effect of priming the pump. The public was definitely becoming interested in radio and Westinghouse extended its broadcasting reach to other population centers, breaking ground on stations in Massachusetts (WBZ), Chicago (KYW) and New Jersey (WJZ).

Gernsback also kept up with his promotions in print, ending 1921 with this editorial:

“To the careful observer, during the past six months it has become apparent that we are finally headed in the right direction as far as popularizing radio is concerned. We may say that we are now right in the midst of a revolution, as far as radio and the great public are concerned. We see the weather marks everywhere. The newspapers are becoming enthusiastic about radio, and devote more and more space to it. The man in the street is beginning to take a lively interest in all things radio. The editor’s desk is beginning to become flooded with letters, not from radio bugs alone, but from the layman, who does not know the difference between a detector and a telephone receiver—all of which is a healthy sign, and we may say that radio is entering into its last and final stage, as far as the public at large is concerned.”

From all appearances, 1922 was shaping up to be a very big year for radio broadcasting.

The author wishes to express thanks to the National Museum of Broadcasting’s Rick Harris; radio collector and conservator, Gary Alley; and to Guy Lancaster and Brian Robertson at the Encyclopedia of Arkansas for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

Further reading

- Ray Poindexter, Arkansas Airwaves, Cassville, Mo.: Litho Printers, 1974

- Thomas H. White, “Battle of the Century” The WJY Story, 2000

- First Broadcast Dempsey–Carpentier Fight July 2, 1921, RCA internal memo, 1921