Author’s collection

It was shortly after World War I that Clarence Thompson, a partner of Lee de Forest, formed a new company Radio News & Music Inc. in New York. His goal was to encourage newspapers to broadcast their news reports by wireless, using de Forest transmitters.

The franchise offer — available to only one newspaper in each city — offered the rental of a de Forest 50-watt transmitter and accessories for $750. Just one newspaper signed up for the deal; it was the Detroit News, led by publisher William E. Scripps.

He had been interested in wireless since investing in Detroit experimenter Thomas E. Clark’s wireless company in 1904. Scripp’s son, William J. “Little Bill,” was an active ham radio operator, operating a station in the Scripps home.

People Might Laugh

Scripp proposed accepting the Radio News & Music offer and building a Detroit News radio station in 1919, but he met resistance from his board of directors. It was not until March of 1920 that he was given the go-ahead to sign a contract.

The de Forest transmitter was shipped to Detroit on May 28, 1920, but was lost in transit; a second transmitter was constructed and sent on July 15. This delayed the installation of the station until August.

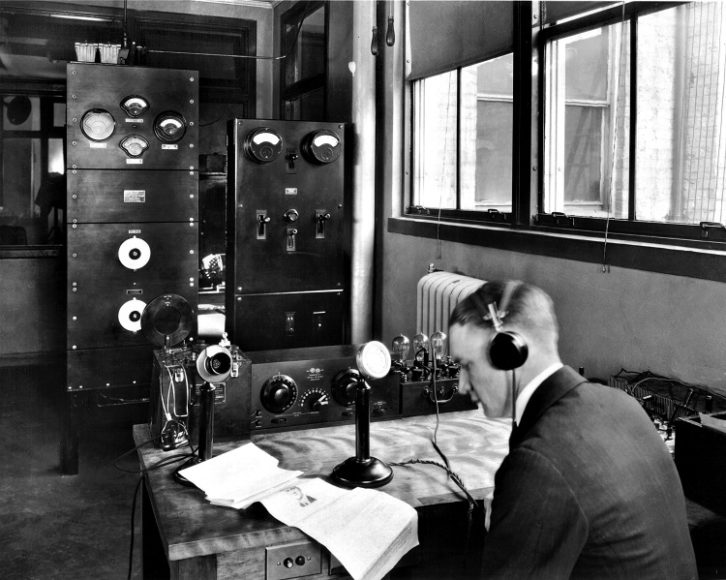

Radio News & Music hired a Detroit ham operator, 19-year-old Michael Lyons, to install the transmitter on the second floor of the News building and to erect a rooftop antenna. A license was needed, but broadcasting in 1920 was just an experimental activity, and broadcast licenses did not yet exist.

The handful of pioneer broadcasters were operating under a variety of license classes, including amateur, experimental and “commercial land station.” The News decided that an amateur license was the most expedient option, and a license was quickly obtained with the call sign 8MK.

Scripps initially worried about the optics of a newspaper giving away its news reports for free over the air, and so he wanted the appearance of an arms-length relationship with the station. For this reason, the 8MK license was registered in Lyons’ name.

In a 1973 letter, Lyons recalled:

I’ll never forget the Tuesday we started broadcasting, and the reporters would not publish the fact, because they were afraid people would laugh at the Detroit newspaper. Besides, I was told, there was a chance the radio news would deter people from buying newspapers to get the news.

8MK made its first transmission on Aug. 20, 1920, on a frequency of 200 meters (1500 kHz), the bottom of the amateur band. It was just a test of the new equipment, and so it was not publicized. It is estimated that no more than 30 people heard the broadcast that night.

Elton Plank, a 16-year-old office boy, was given the task of being the first announcer because of his pleasing voice. At 8:15 p.m., Plank placed a megaphone against the transmitter’s mouthpiece and announced, “This is 8MK calling, the radiophone of the Detroit News.”

He then signaled Howard Trumbo, operating a borrowed hand-crank Edison phonograph, to play two records: “Roses of Picardy” and “Annie Laurie.” Listeners were asked to telephone in their signal reports to the newspaper, and 8MK signed off the air.

Election Bulletins, August 2020

After several more test transmissions verified the equipment was working properly, 8MK made its first publicized broadcast on Aug. 31, 1920, the night of the state’s primary election.

A front-page announcement in the News alerted the public to the upcoming broadcast: “Miscellaneous news and music will be transmitted from 8 until 9 o’clock so that operators may adjust their instruments. Election bulletins begin at 9 o’clock and will continue on the hour and half-hour until midnight.”

An estimated 500 listeners heard that night’s broadcast.

After that auspicious debut, 8MK began a schedule of two broadcasts per day, six days a week, featuring news and weather summaries from the pages of the Detroit News combined with entertainment from phonograph records.

Each day, the program schedule of the “Detroit News Radiophone” was published on the front page of the newspaper. Encouraged by the positive results of his radio experiment, Scripps transferred the 8MK license into the name of the newspaper and dedicated more resources towards his fledgling operation.

A staff of three was assigned — two engineers and a program manager. New program concepts were tried: in September, there was a remote broadcast of live dance music by the Paul Specht Orchestra, and the results of the Dempsey-Miske boxing match were announced. The Brooklyn-Cleveland World Series baseball play-by-play scores were sent out in October.

On Nov. 2, 8MK broadcast the Harding-Cox presidential election returns, the same night as KDKA’s famous first broadcast. Live Christmas carols were broadcast in December. Lectures, dramatic readings and poetry were added in 1921, and live music was increasingly being heard.

Although still operating under an amateur license, 8MK was a commercial broadcaster in all aspects, operating from a business establishment with a paid staff and professional content.

National Coverage

In the fall of 1921, new government regulations were issued that prohibited amateurs from broadcasting news and entertainment.

This meant that the Detroit News, along with dozens of other pioneer broadcasters, were required to apply for a new class of license called “Limited Commercial.” Subsequently, in November, 1921, the “Detroit News Radiophone” received a new license with the randomly-assigned call letters WBL, and it moved to the new shared broadcasting frequency of 360 meters (833 kHz).

But when listeners had trouble hearing the call sign correctly, a new call sign was requested, and the Detroit News station became WWJ on March 3, 1922.

Scripps now poured considerable resources in his radio operation. A new WWJ studio/office suite was built on the fourth floor of the building. A 290-foot antenna was stretched between the News building and the Fort Shelby Hotel in 1921, and a 500-watt Western Electric transmitter was installed in 1922, only the second factory-made broadcast transmitter in the country.

With these improvements, WWJ was now being heard across the country at night. By summer, there was a full-time staff of nine. Live broadcasts of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra began in February, and in May a new 16-piece WWJ Orchestra was organized, consisting mostly of symphony musicians. Regular church services were broadcast on Sundays.

Star performers appeared on the station, including Fanny Brice and Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians. Nightly news reports with running commentary were delivered by Albert Weeks, billed as “The Town Crier.” Children’s bedtime stories were being read nightly.

As local live talent was hired to broadcast on WWJ, some refused to believe there was really an invisible audience hearing their performances. They were accustomed to the immediate feedback of a live audience, but the microphone offered only silence.

When future radio comedian Will Rogers made his first ever radio broadcast over WWJ in October, 1922, he didn’t believe that people were really listening: “I don’t think you can hear me,” he announced. “If this isn’t the bunk, let me know if you can hear me.”

To his great surprise, he received letters and postcards from all over the Midwest. Even Henry Ford had heard him, using a receiving set he had built himself.

Live remote play-by-play broadcasts on WWJ began in October, 1924, when Chief Announcer Edwin “Ty” Tyson called a University of Michigan football game from the stadium. The university allowed just this one broadcast because the stadium was already sold out, but when they were flooded with ticket requests for the next game they agreed to allow regular broadcasts.

In 1927, Tyson broadcast the entire season of Detroit Tigers home games over WWJ. He soon became one of the country’s foremost early sportscasters, and called both the 1935 and ’36 World Series games for NBC.

In 1923, WWJ moved to 517 meters (580 kHz), sharing the frequency with the new Detroit Free Press station WCX (now WJR), and then in 1925 it moved to 850 kHz, operating full-time with a new 1 kW transmitter. After the company’s new parking garage was completed across 3rd Avenue in 1926, the transmitter moved into the garage building, and two new towers suspended the antenna 265 feet above street level between the garage and the paper warehouse.

(WWJ was shifted to 920 kHz in 1928, and then to its current 950 kHz frequency in the NARBA Treaty realignment of 1941.)

Showcase Station

As radio entered its “golden age” in the 1930s, backed by the ample resources of the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain, no expense was spared to make WWJ a first-class station.

When the NBC Red Network was organized in 1926, WWJ became its Detroit affiliate. In 1936, a new showplace five-story studio building was built for a cost of $1 million, and an opulent 5 kW transmitter building and new tall tower were inaugurated. Both structures were designed by the famed Detroit architect Albert Kahn.

Author’s collection

Frequent remote broadcasts originated from a fleet of remote trucks and the Detroit News aircraft. “Radio Jake,” the WWJ Interference Engineer, prowled the city in his own vehicle, solving interference complaints for citizens as a free public service.

The Detroit News had operated WWJ entirely as a goodwill service to the public. By 1928, it had reportedly invested $466,000 in the station, despite earning not a penny in return.

There was no way knowing if WWJ benefited the company through increased newspaper sales. This was the conundrum of radio in the late 1920s — it was now an essential public service, but had no clear source of revenue. It was not until advertising was permitted in the early 1930’s that radio became a profitable medium.

WWJ was continually at the forefront experimenting with new broadcast technologies. In 1938, it transmitted a radio newspaper during overnight hours to facsimile printers in local residences. In 1936, it inaugurated an experimental “Apex” high-fidelity AM station, W8XWJ, broadcasting on 41,000 kHz from the top of the Penobscot Building skyscraper.

In 1940, this was converted to W45D, one of the nation’s first FM stations (now WXYT-FM). And in 1947, WWJ-TV took to the airwaves (now WDIV).

The 65-year relationship between WWJ and the Detroit News ended in 1985, when The Gannett Company bought the newspaper and spun off WWJ/WJOI to a group of local businessmen. Then in 1989, they were purchased by CBS Radio, who invested in a major power increase to 50 kW in 2000.

In 2017, CBS Radio merged with Entercom, today’s owner of WWJ, which coincidentally also owns pioneer stations KDKA and KNX. The original WWJ de Forest transmitter was donated to the Detroit History Museum in 1959, where it can be seen on display today.

For more of John Schneider’s history articles, including other centennial stations that were heard prior to the famous KDKA broadcast of 1920, visit www.radioworld.com/author/johnschneider.