Pirate radio seems to be in the trade news quite a bit these days. It has certainly been a hot topic of discussion at the FCC and among licensed broadcasters. Pirates are springing up all over the place, in virtually every market, often causing interference to licensed broadcasters and sometimes boldly competing with them for advertising dollars.

The situation is made doubly bad by the staffing situation at the FCC Enforcement Bureau. With the closure of a good number of field offices and the remaining offices significantly understaffed (often with just one agent in place to cover several states), pirates know the odds are on their side. They probably will get away with it, at least for a while.

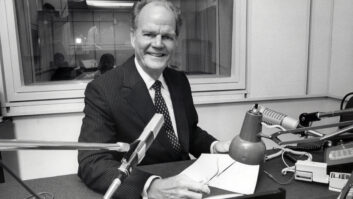

The author uses a portable spectrum analyzer and four-element Yagi antenna to “DF” a pirate station. Once it was determined that the signal was coming from this house, relocating to the retail area behind it made it possible to identify the antenna, which was on the back deck railing.

Even when the FCC has focused on shutting down pirates in specific areas, I’ve heard that the exercise is often akin to “Whac-a-Mole,” with another (or the same) pirate popping up in a different location within days or even hours of being shut down.

I recently read an interview with a pirate broadcaster. In the interview, the pirate indicated that there is nothing wrong with what he is doing. I think that attitude is prevalent at one end of the pirate spectrum. At the other end is a more anarchist viewpoint: The pirates know what they are doing is wrong and just don’t care.

Whichever species of pirate, the situation is incredibly frustrating for legitimate broadcasters, including (and perhaps especially) LPFM and translator licensees who lack the power to drown out co- and adjacent-channel pirates.

Clearly we need aggressive enforcement action at the federal level, but with limited resources and personnel, that is unlikely, at least in the short term. So what can we as broadcasters do?

It has been my experience that if we will do the legwork, the FCC will often jump on a pirate in a hurry. I have dealt with pirates twice in recent months; and both are now gone, thanks at least in part to FCC field agents.

A TALE OF TWO PIRATES

At the beginning of 2016, as the first translator window opened, I began listening around Denver on the frequency I filed for. Right here in my office on my office radio, I was hearing a strong signal with an eclectic music mix, time and temperature announcements and liners. There was, of course, no station ID.

I spent some time driving the signal and found that it went several miles in each direction, centered very near my office. This was no legitimate Part 15 operation; the station had to be transmitting considerable power. We had to find this station and get it shut down before our new translator came on.

Amanda Hopp, chief engineer of our Denver cluster, drove while I used a Yagi antenna and a spectrum analyzer to direction find (DF) the signal. We started in the office parking lot and got a bearing west, so west we went a quarter mile or so to a condo complex.

From the parking lot of that complex, I got another bearing, this time east. We took a couple more signal shots from that general area and confirmed that east was indeed the right direction. So we went a half-mile east into another condo complex, this one right across the street from the high-rise where my office is located. From there, signal bearings were indicating north, although there were plenty of reflections off the several high-rises in the area.

Going north a quarter mile or so into a residential neighborhood, I found the signal was much stronger. I took several signal bearings and triangulated them to a particular block. Once on the block, I got out of the car and started walking.

It didn’t take long to pinpoint the signal as emanating from a particular house. I saw a small whip antenna on top of a cooler on the roof and initially thought that was the pirate’s antenna, but then I went around behind the house, which conveniently backed up to a gas station, I saw a fiberglass whip about 10 feet long on the rear deck. I pointed the Yagi at that whip and confirmed that was indeed the pirate radiator.

Back at the office, I emailed the local FCC EB office and provided them with all the details. I got an almost immediate response that an agent would be sent out to the house within a couple of days, and that’s exactly what happened.

When the agent got there, he noted that the measured field appeared to be close to Part 15 limits, so he didn’t even knock on the door. Amanda and I drove the signal again and found it was nowhere near what it had been. It was listenable only within a few hundred feet as opposed to several miles.

So what happened? As I was wandering up and down the sidewalk in front of the house with spectrum analyzer and Yagi, there was a man walking his dog in that same area. I suspect that this was either a neighbor or the pirate himself. Either way, the pirate cut power back to a legal level before the FCC agent arrived. Problem solved, right? Not quite.

I knew that if this guy continued to transmit on our translator frequency, we would have a tough time hearing the translator at our studio, and that now-legal Part 15 FM station would poke a pretty good hole in the translator coverage right on a major commuter route. The signal really needed to go away.

On a lark, I googled the street address of the house, and amazingly, one of the returns showed that the owner was an amateur radio operator. That reminded me of the short whip antenna on top of the rooftop cooler, now undoubtedly a 2-meter ham antenna. I looked up the guy’s call sign, got his full name and wrote him a polite but firmly-worded letter on company letterhead advising him that within a few weeks, a licensed station would be coming on the air on the frequency he had chosen for his Part 15 station. I asked him to find another frequency and left him with the strong implication that we would not take interference to our new signal lying down.

Amazingly, within a couple of days, the signal disappeared and has not come back. I listened up and down the FM band to see if he moved to a different frequency but could not find him. The fiberglass whip is now gone from the back deck. This pirate has wisely given up his pursuit of unlicensed broadcast activity. I say wisely because in engaging in unlicensed broadcast activity at greater than Part 15 levels, he not only risked a hefty fine but also his amateur radio license.

Credit: iStockphoto/pgaborphotos

“AND IT’S LEGAL!”

Our translator CP was granted, and very shortly we had that signal on the air from high atop Lookout Mountain.

The coverage of the Denver market was excellent, but we began getting reports of an interfering signal in the north metro area. There were no co-channel stations within 100 miles, so we knew this was not coming from a legitimate broadcaster.

One complainant gave us a lot of detail about the pirate’s signal, programming and the like. This guy was boldly identifying as “Pirate Radio 95.3 — and it’s legal!” Like the first pirate, he played a very eclectic mix of music and even some talk programming, and he had no filter — all of George Carlin’s seven words made it on the air on a regular basis.

Once again, Amanda and I loaded up our equipment and antenna and headed north, into the area where our complainant lived. This time we used a modified Icom R-7000 receiver that had an S-meter and an RF attenuator. We used the same Yagi antenna as before.

We started on a ridge southeast of Boulder and got a bearing northwest. Heading north, we got another bearing, this time west. We kept going north past Boulder and got several conflicting bearings, but the signal was weaker up there so we headed back into Boulder. That’s where we were seeing the strongest signal, but it was anyone’s guess where it was coming from. We were getting reflections from the mountains to the west and from buildings on and off the University of Colorado campus.

At one point, we just started driving the residential street grid between the campus and the foothills. There was still no definitive direction, but the signal was getting stronger. We finally narrowed it down to an area of a few square blocks, but we could not identify the source location.

Back at the office, I again contacted the Enforcement Bureau office and gave them what we had. Within a few days, an agent had gone out and located the pirate station. It turned out that this guy was pretty well known to the FCC and had a history with them. The agent got some Boulder city police officers to accompany her and knocked on the door. At the end of that visit, the pirate was shut down and has not been back on, at least not on our frequency.

NO ANTENNA!

I later spoke with the field agent and asked how she found the pirate with all the reflections in the area. She said she disconnected the antenna completely from her receiver and drove the street grid until she heard the signal pop up. At that point, she was right in front of the house. The antenna was hidden in the trees in the backyard, and the signal propagated so well because of both relatively high power and the mountains just west of the pirate’s location, which made a great, high-elevation reflector.

Interestingly, we got some “hate mail” after that Boulder pirate was shut down. Evidently he had a following. To put it politely, the pirate’s listeners who posted on our station’s Facebook page could not understand why he had to shut down because his signal could not possibly be interfering with our station way down in Denver. It’s always hard to explain to the uninitiated that a radio signal will interfere over a much larger area than it covers.

With the resolution of these two cases, we’re two for two, at least in the Denver market. The key in both cases was taking care of the time-consuming aspect of the hunt ourselves, before contacting the FCC. That really left the field office people with very little to do, really just show up.

My guess is that this is going to be the model that broadcasters are going to have to follow.

Cris Alexander, CPBE, AMD, DRB, is director of engineering of Crawford Broadcasting Co.