The National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting has been around for more than 20 years, but a project supported by a $500,000+ grant has transformed its World War II-vintage building — the former VOA Bethany “relay station” transmitting plant — into a world-class repository of communications history and knowledge.

The 30,000-square-foot, two-story building was deeded over to the township of West Chester, Ohio, following the VOA’s closing of the station in 1994. Little of it would be recognizable to those present when transmissions began in late 1943.

The facility was constructed by the Crosley Broadcasting Corporation under a contract from the Office of War Information as part of the initial VOA initiative to disseminate accurate reporting of wartime news to Axis nations. It had languished and fallen into disrepair following its abandonment by the VOA. The infusion of funding now allows artifacts to be better displayed, as well as making the facility more accessible (and comfortable) for visitors.

The largest item on display is a 1960s-vintage 250,000-Watt 821A Collins shortwave transmitter that was “abandoned in place” when the GSA ceded building and grounds ownership to the local government.

The giant transmitter has been extensively labeled to allow visitors to better understand what they are viewing. And while the government did remove the antennas and masts, museum volunteers have constructed scale models to illustrate how the site once appeared.

Another visible former VOA item is the large control room where switching and monitoring operations took place.

Telling the story

The facility is anchored by VOA artifacts and exhibits, but Jay Adrick, president of the museum board, is quick to remind visitors that from the 1920s onward, Cincinnati, just south of the Bethany site, was a broadcast industry “hub.” This heritage is reflected in exhibits.

“In addition to Crosley’s massive manufacturing and broadcasting operations, Cincinnati was home to the Kodel Radio Corporation, the original owner of station WKRC,” said Adrick. Other radio receiver and equipment manufacturers calling Cincinnati home include the Midwest Radio Corporation, which sold their products directly to consumers.”

“There were about 40 radio and radio parts manufacturers in the Cincinnati area,” added Lee Hitte, a museum curator and docent. “This was the ‘Silicon Valley’ of its day. It was the center of broadcasting, the center of radio, and the center of the technology at the time.”

Crosley’s flagship WLW once had the distinction of being the most powerful radio station in the country, operating with 500,000 Watts during the 1930s, and referring to itself as “The Nation’s Station.” To provide programming, Crosley amassed an impressive group of entertainers and personalities, many of whom would become nationally famous. Museum visitors have the opportunity to experience some of this broadcasting history through exhibits featuring profiles of several of the on-air performers.

[Related: “National VOA Museum of Broadcasting Plans Anniversary Party”]

While the 1/4-megawatt Collins rig is the largest such item in the collection, it is by no means the only transmitter. Volunteers have restored to like-new condition an early 70-kW shortwave transmitter built and used by Crosley. Other artifacts include a massive 100-kW water-cooled triode, one of 22 used to power the WLW 500-kW rig.

Transmissions live on

Although the VOA’s Bethany facility transmissions ended more than three decades ago, the facility still sports transmitting antennas and operational HF gear in the form of a large amateur radio operation. WC8VOA features four operating positions and is operated by the West Chester Amateur Radio Association, a division of the museum.

In addition to the array of modern amateur radio equipment used by the station, the museum features a comprehensive collection of vintage ham gear from many U.S. manufacturers, including Ohio-based R.L. Drake.

In addition to broadcasting and manufacturing radio receivers, the Crosley organization diversified into the production of numerous non-radio products, including the first refrigerator to feature shelves on the inside of the door (the “Shelvador”), a device marketed to stimulate hair growth (the”Xervac”), a refrigerator for use in areas without electricity (the “IcyBall”), small automobiles and even a line of kitchen cabinetry. Carefully restored and documented examples of all are on exhibit.

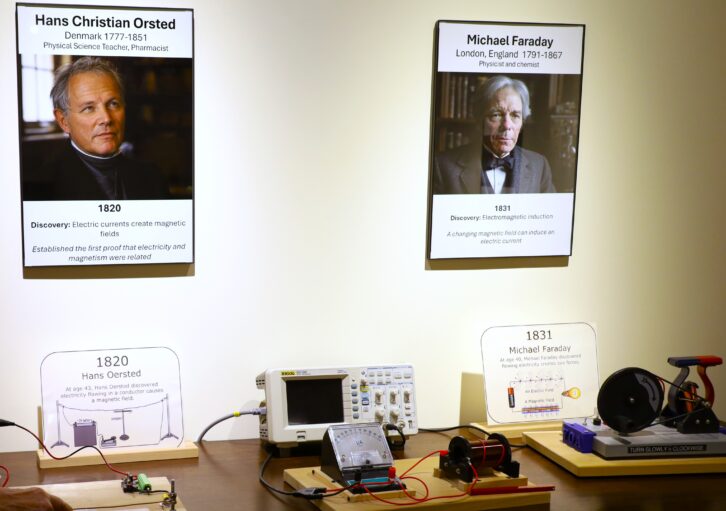

In addition to the visual “candy” on display, the museum features a hands-on gallery, the “Foley Pit,” where visitors are encouraged to try their hand at creating the sound effects such a wind noises, hoofbeats and thunder that played a big part on setting the stage for radio dramas. The museum also features a “timeline” gallery depicting scientific discoveries that led to radio’s development.

The makeover

Adrick and Jack Dominic, the museum’s executive director, said that when the building was deeded over, it had some serious deficiencies for museum purposes.

“One of the big issues was that there was no heating system,” said Adrick, explaining that this had not been a problem in the operation’s former life, with big transmitters running round the clock and giving off plenty of waste heat.

The Americans With Disabilities Act did not come about until 1990, so accessibility was another issue that had to be addressed. A new entrance was created so visitors can enter without navigating the steep stairs.

Funding from an Ohio state grant and a private donor enabled these and a number of other beneficial modifications and additions to be made to the 80-year-old building.

“The former east side garage has been turned into a conference center and a food preparation facility added,” said Adrick.

Even with the upgrades and improvements, the museum is still a “work in progress,” with plans underway for expansion of the existing STEM gallery, additions to the Media Heritage highlighting Cincinnati-area radio and television personalities and performers, and a new exhibit focusing on broadcast news.

“This will be the history of television news as it relates to this region,” said Adrick. “We have four TV stations that are generating newscasts, but the first, WLWT, began their newscasts in 1948. A lot of technology and early firsts occurred in this market. Crosley built COMEX [the Communications Exchange building] as a news center for both radio and television, and had the first weather radar in the country, outside of the National Weather Service. So, we’ll be developing a rather detailed exhibit around that theme.”

The National Voice of America Museum of Broadcasting is at 8070 Tylersville Rd. in Chester, Ohio, easily accessible from both I-71 and I-75. The museum is open to visitors from noon until 4 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays.

And what about those cuts?

The museum is a non-profit and not part of Voice of America itself. It does not receive federal funding, so recent actions by the Trump administration to close or dramatically shrink VOA and other U.S. international broadcast operations do not touch it directly.

[Related: “Voice of America Fights Its Way Back”]

“Any decision in Washington regarding VOA will not affect operation of the museum,” said Executive Director Jack Dominic in a video on the museum website.

He said that in some countries, VOA has been “the only non-censored window on the world,” as becomes clear from the comments of foreign visitors who listened to the Voice of America.

“It is not uncommon to see these people break out in tears as they remember how significant the broadcasts were, and how the broadcasts contributed to their ability to hear factual and truthful information. … The museum will continue to be a place where the Voice of America is celebrated as one of the most effective uses of broadcasting.”