A New Battle Is Brewing Over Usage of Digital Music Delivered Via Digital Radio

Last time we considered how to make radio content less perishable and thereby more appropriate for short- or long-term storage. This discussion was aimed primarily at podcasting of selected radio broadcasts, but there’s another closely related issue that has been making waves lately, and which may have strong impact on future radio business.

To best understand this issue, a review of context is helpful.

Listen vs. store

First, recall that the music recording industry has taken great pains to prevent the storage of webcasts by consumers. There are several provisions in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, or DMCA, that address this point specifically. Through its primary trade association, the Recording Industry Association of America, the industry also is currently lobbying hard to have similar restrictions applied to IBOC digital radio.

Next, you may have noticed the strong response over the past year or so to XM Satellite Radio’s XM2Go products, as well as Sirius Satellite Radio’s handheld devices that could receive, and in some cases, store satellite radio content.

Importantly, the satellite radio was careful to steer clear of most of the recording industry’s concerns by offering the storage-capable devices with no digital audio I/O, no removable storage and no ability for much user interactivity with the recorded content.

In fact, although described by some as “TiVo for satellite radio,” these units were really more akin to digital VCRs, in that recording content was only possible by hitting a record button in real time while listening to a particular channel, or by presetting a channel, start and stop time for a future recording. Once recorded, content could only be played or deleted – no editing was possible – and storage was initially limited to about three hours. (Some manufacturers’ XM2Go units now hold as much as five hours of content.)

Recently, however, both satellite radio firms have announced plans to introduce next-gen handheld receivers with decidedly different functionality.

In July, XM announced that at least one consumer electronics manufacturer will produce devices in time for the holiday buying season this year, which combine MP3 player capability with satellite radio reception. Shortly thereafter, Sirius released information on its upcoming S50 receiver, a portable device about the size of the original iPod, which was planned to be on store shelves this month.

New rules?

These units will greatly increase the storage capacity for recording satellite radio – perhaps up to 50 hours. But a more controversial attribute of the new devices is their potential ability to allow users to edit a recorded satellite radio stream and store individual songs (or other content elements) as separate files on the device, while deleting others from the recorded stream.

In at least some cases, this capability would reportedly come at no additional charge to subscribers, which in the record industry’s view amounts to a free download.

Some in the music industry apparently feel that this crosses a line from transitory to permanent storage of copyrighted material, which violates current legislation and/or licensing agreements. They predict that quick litigation will follow if the products are released as apparently planned. Meanwhile, the satellite radio companies reportedly feel that they are on defensible legal and licensing grounds with this move.

More practically, the recording industry and others are concerned that this capability will thwart the growth of nascent but increasingly popular paid music download services. (However, some pre-release product literature indicates that recorded songs from satellite radio can only be “tagged” for later purchase from an online music store. It is likely that this variant would be acceptable to the music industry, so it could indicate a potential way out of the impasse.)

At press time, the controversy had not yet produced much in the way of public pronouncements, as the engaged players refrain from comment and sensibly try to work things out. But there’s apparently been no shortage of heated debate in those discussions; and if the wide gulf in positions persists, it is likely that this will spill into the public record soon, if it hasn’t already by the time you read this.

Other potentially controversial, but as yet undetermined, issues will be whether these or future devices include digital audio I/O or other digital interfaces – USB, IEEE 1394, WiFi, Bluetooth, USB, etc. – and whether any removable storage, such as SD cards, can be fitted. Also critical will be the level of predetermination of upcoming content (i.e., playlists in advance) or any other search or automated recording features, which would allow a user to set the device to capture particular songs wherever and whenever they appear.

Finally, the parameters of any rights management applied to stored content will be of concern, particularly if transfer of copyrighted material to PCs or other digital devices is possible.

Yet another consideration is whether the audio quality of satellite radio is up to the task for a music download modality. But of course, if such capability is available at no additional cost, this issue may be of little concern to subscribers who are already satisfied with the audio quality of real-time satellite radio service.

Deep impact

This predicament could appear to be just another of what seems a nearly limitless sequence of thrusts and parries between content owners, conduit operators and consumer electronics manufacturers.

What is salient about this particular case is that its outcome could resonate beyond the specific parties involved. If a precedent is set that allows such functionality to be applied to broadcast music streams, it could open the door for webcasts and even IBOC digital terrestrial radio to do the same.

A contributing factor here is the strong climatic shift in the federal legislative and regulatory environment away from applying different rules to different delivery systems. (This is the primary motivation behind the current move in Congress to revise the Telecom Act of 1996, the fundamental law behind all U.S. communication regulations.) Given this, what’s found to be acceptable on one medium is more likely to be applied broadly to all or many others.

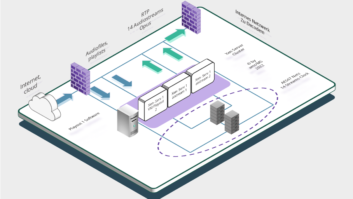

Thinking ahead, though, even if such functionality were to become possible for terrestrial radio broadcasters, it is almost certain that a business – or perhaps even a regulatory – prerequisite would be the inclusion of some form of content protection limiting the usage and redistribution of such content, as is already inherently provided by satellite radio’s conditional access systems. (Note that the current systems used by satellite radio may not be adequate for the type and/or level of protection required for some of the envisioned functionality of these devices, however – at least in the music industry’s opinion.)

More on the options for adding such content protection technology to terrestrial digital radio broadcasting, and the RIAA’s already stated preferences in this area, in the next issue.