Editor’s note: The window for filing applications for new LPFM stations has been pushed back. It will now run from Dec. 6 to Dec. 13. Learn more here.

The possibility of winning a license to operate an FM radio station might appeal to many small community groups. But low-power advocates say launching an LPFM is expensive and that it involves multiple challenges and a steep learning curve.

The FCC’s announcement that it will open a filing window in November to take applications for new LPFMs — the first such opportunity since 2013 — is welcome to community radio boosters.

The low-power service was created by the commission in 2000 when it authorized a new form of noncommercial educational broadcasting with a maximum of 100 watts. Advocates have been pushing the FCC for technical upgrades to improve reception; some would like a boost to 250 watts, which is opposed by the National Association of Broadcasters.

Most LPFMs serve small communities and rural parts of the country with an approximate range of about 3.5 miles, according to the FCC.

LPFMs, ranging across the FM band from 88.1 to 107.9 MHz, are for schools, churches, non-profits, government or other educational institutions. Educational entities can file one application. Tribal governments can file up to two. State and local government agencies may file as many as they need within their jurisdiction for the purpose of public safety.

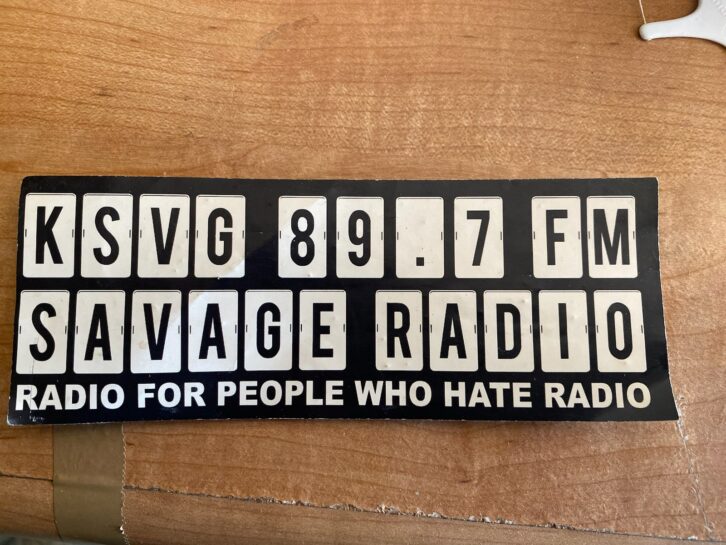

LPFM stations often fill a niche in a community, supporters say. The ideal is to be hyper local with an intriguing format. For instance KCJV(LP), licensed to Leon Springs, Texas, airs a non-traditional format playing B sides from oldies singles. Its branding slogan seems appropriate: “The Greatest Songs You’ve Never Heard.”

The number of licensed LPFMs has fallen from its high. FCC data showed 1,989 LPFM stations on air at the end of June, down by 45 licenses over the past year. At one point a few years ago there were about 2,100.

“The number of LPFMs has, indeed, been trending downwards, and there are some good and bad reasons for this,” said Jim George, founder of the online LPFM Database, which tracks data on the FM service.

“The good news is that some LPFM operators took advantage of the FCC’s 2021 noncommercial filing period and applied for full-power stations in their communities, so some have turned in their LPFM licenses.

“In addition, some LPFMs just couldn’t make it through the pandemic. A majority of LPFMs have little to no budget and depend on underwriting or contributions from their listeners. The financial strain of the pandemic hurt a lot of operators and while some soldiered on, others just couldn’t make it.”

Dozens of LPFM stations are on the membership roster of the National Federation of Community Broadcasters, according to Sally Kane, CEO of the organization.

Kane says the success of any LPFM boils down to some crucial foundational elements.

“The biggest challenges they face seem to be limited organizational capacity for fundraising, experience with nonprofit governance and finding a steady and reliable flow of content to broadcast,” Kane said.

NFCB provides its members administrative resources and professional development opportunities. It had not seen an uptick in potential licensees seeking information about the new LPFM filing window as of July, a few weeks after the window was announced.

Realistic expectations?

Paul Bame, engineering director for community radio group Prometheus Radio Project, partly blames the pandemic for the recent decline in the number of LPFM stations.

“Over the years, I’ve seen single-champion stations fail when the champion gets tired of it or move on, and sometimes that happens within otherwise-healthy nonprofits. Some stations ran out of money, for example they had an unsustainably large tower-rental bill and no affordable options.”

Some LPFM applicants may have unrealistic expectations about the coverage area of a 100-watt FM station and the related ability to fundraise, Bame said.

“I encounter people with both realistic and unrealistic coverage expectations compared to the supposed nominal 5.6 km range. But to make that more complex, in the field I see different stations’ coverage range from 2 to 14 miles, so who’s to say what’s realistic?”

In some cases LPFM coverage is curtailed by translators or HD interference within the LPFM’s primary service area, said Todd Urick, director of nonprofit advocacy group Common Frequency. He noted the boom in the number of FM translators serving AM stations.

“LPFM signal quality and sustainability has deteriorated with the abundance of cross-service FM translator licensing. LPFM distance-based engineering methodology is outmoded and never contemplated this. The issue could be strategically addressed [at the FCC] by a modest power upgrade and migrating to a contour-based engineering methodology like translators,” Urick said.

LPFMs are not protected from interference from full-power stations and are considered secondary to existing and modified full-service FM stations. The LPFM must accept interference from primary stations, even if the LPFM station predates the primary station.

The most common question Urick has heard about the filing window is simply “Is a channel open near me?”

There are 8,935 FM translators and boosters, according to the latest FCC count; the commission does not report those two separately.

The opportunity for new LPFMs in major urban areas is limited, in part because of the increase in translators granted in the AM revitalization push. But experts say there are still plenty of places in the United States where LPFMs will be available.

The opportunity is expected to be significantly larger than the availability of reserved band NCE FM channels in the 2021 filing window. Just how many new low-power FM licensees will result from the filing window, set for Nov. 1–8, is unknown.

Most observers predict there will be thousands of applications. In 2013, the FCC received about 2,800 LPFM applications.

“Zeitgeist and artistic identity”

Among the arguments cited by early opponents against an LPFM service was that stations might run roughshod over FCC rules and policies, pirate-radio style.

Chaos did not break out on the FM band. And while some LPFM stations have been dinged for airing commercials — in July KRIM in Payson, Ariz., agreed to pay a $20,000 penalty for airing for-profit announcements over a two-year period — technical issues are more likely to be the focus of FCC enforcement, said Jim George.

“I’ve seen where some are transmitting from a location other than their licensed location and/or using higher power than they’re authorized.”

Another consultant reported cases where LPFM stations have not made necessary filings with the FCC such as transfers of control, silent notifications or participation in the EAS National Periodic Tests.

Proponents believe that the best LPFMs have validated the entire concept of such a service.

“I think the broadcast industry tends to be critical about the technical performance of LPFM and never views the success stories in terms of local content,” said Urick.

He pointed to stations such as KUZU Denton, Texas; KWNK Reno, Nev.; KFFP Portland, Ore.; and WXNA Nashville, Tenn., which he said have “impressive community involvement with a mosaic of programming that reflects the music and culture of the cities — a commitment that commercial radio lost decades ago. LPFMs like these encapsulate the energy, zeitgeist and artistic identity of the cities that have made the radio service completely worth it.”

Some community groups that lost out in 2013 may have lost interest due to the long wait between filing windows.

But Michi Bradley, founder of REC Networks and longtime LPFM advocate, says her group has already received inquiries from secular and faith-based organizations, from Puerto Rico to Hawaii. She says lots of groups still see potential in LPFM.

“With the continued decline of AM radio and the threats of losing AM receivers in cars, this may be a good opportunity for public safety agencies, which have specific carve-outs in LPFM, to be able to obtain FM facilities for use as Traveler’s Information Stations,” Bradley said. “There also will be opportunities for tribal entities to obtain stations.”

Advocates recommend that someone hoping to seek an LPFM consider using a consultant for preparing the application and filing the paperwork. There have been changes in FCC policies and rules since the 2013 window, including a new application filing system and the use of directional antennas.

[Sign Up for Radio World’s SmartBrief Newsletter]

“Even though the FCC insists that LPFM must remain an easy service, much to its detriment, we always suggest that applicants get hired help,” Bradley said.

“While it may be possible for an application to be filed unassisted in some cases, many more cases — such as those where there are second-adjacent channel short spacing — require someone who has access to systems that can determine field strength contours, understands the elevation patterns of various antenna configurations and understands the FCC’s requirements for waivers.”

REC Networks runs a website, LPFM.app, that checks potential availability. (Bradley cautioned that some online resources offering searches for low-power FM signals are intended for Part 15 short-range devices such as transmitters that plug into automobile lighter plugs and allow cellphone audio to be heard on an FM radio.)

Like everything else across the economy, most LPFM consultants believe the cost of building a startup LPFM will be significantly higher than in 2013. Bame of Prometheus says it is hard to peg the exact expense of founding a station.

“Until the (applicants) have some actual information about their needs, site and complications, $30,000 might be a good low initial fundraising target,” he said. “With tons of DIY and knowledgeable compromises, it could be done for less.”

Such estimates must include the cost of an EAS decoder. An LPFM also must use a transmitter that is FCC certified, with an FCC ID number valid for Part 73 use.

“There are many cheap imported transmitters on the market available through eBay, Amazon and the Chinese e-commerce sites that are not certified for LPFM use,” said Bradley.

“Even some ‘hand me down’ broadcast gear, which may be permitted for use in the full-service and FM translator service, are not legal in the LPFM service. LPFM has a specific requirement.”

Several experts contacted for this story said a pending book, “Low-Power FM for Dummies,” will be a good resource for prospective LPFM licensees. The book is expected to be published in October, according to its listing on Amazon, but may be available sooner. Its author is Sharon Scott, co-founder and general manager of WXOX(LP) in Louisville, Ky.

Contour Methodology?

The above article mentions the distance-based engineering methodology used by the FCC and a suggestion that it should migrate to a contour-based methodology.

Michi Bradley of REC Networks commented on that:

“LPFM having contours towards full-power stations where the existing distance separation requirements are not met would require an act of Congress because of the Local Community Radio Act,” she wrote in an email, “although the commission could, if it chose, use contours for service higher than LP-100 as long as minimum distance separations are met and still remain within the statutory limitations of the LCRA, which is an argument REC made in the past.

“LPFM having contours towards translators is not specifically statutorily prohibited by the LCRA. This was one of the issues we raised in our previous LP-250 Petition for Rulemaking RM-11810, which was dismissed by the FCC as being ‘too complex,’” she continued.

“The real issue is that the FCC needs to stop regarding LPFM as being this service that needs to be ‘simple.’ A majority of applications were handled with hired help. RM-11810 addressed that fact. There are things that can be done, but the FCC is not willing to do them.”