The Federal Communications Commission has adopted several changes to its rules for emergency alerting in the United States.

This order makes the changes we described in our recent story “Changes Coming in National Alerting.”

On the mobile phone side of things, the FCC doesn’t want people to opt out of receiving critical information, so it has combined the existing “Presidential Alerts” category, which is non-optional on devices that receive Wireless Emergency Alerts, with alerts from the FEMA administrator to create a new non-optional alert class called “National Alerts.”

On the EAS front, the commission is requiring State Emergency Communications Committees to meet at least annually and submit plans for FCC approval. Also it is encouraging states to review the composition and governance of their SECCs (or to form a committee one, if one doesn’t exist).

The FCC also plans to provide a checklist of information that should be included in annual state Emergency Alert System plans, and will tighten up its process for reviewing those plans. (We’ll report on that when the full order text is available but you can read the draft order that was released ahead of the meeting.)

The order also specifies that government agencies may report false emergency alerts to the FCC’s 24/7 Operations Center. And it clarifies how alert originators can repeat their alert transmissions.

Congress had instructed the FCC to work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to adopt such rules.

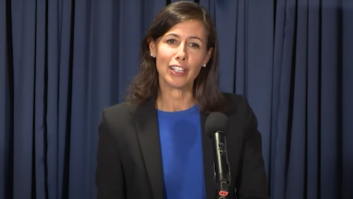

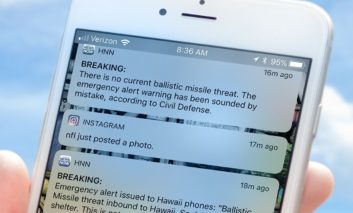

“When alerts work well, we get the facts we require in an emergency,” said Acting Chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel in a statement. “But when they fail, they can cause fear and confusion and even panic.” She cited the 2018 incident when people in Hawaii got an emergency alert warning of a ballistic missile threat and were told “This is not a drill.”

Rosenworcel said the Hawaii incident led her to call for a system for reporting false alerts “so we can learn from our errors going forward,” and to urge the use of state emergency communications plans to promote best practices.

“This is progress. But there is still more to do,” she continued. “So today we are kicking off a rulemaking to discuss additional ways we can improve alerting, based on recommendations from our colleagues at FEMA.”

She also made note of the nationwide test of the Emergency Alert System and Wireless Emergency Alerts that is scheduled for August.