Some things never go out of favor. One is the disc phonograph record. Even after more than 130 years, it’s still very much alive here in the 21st century.

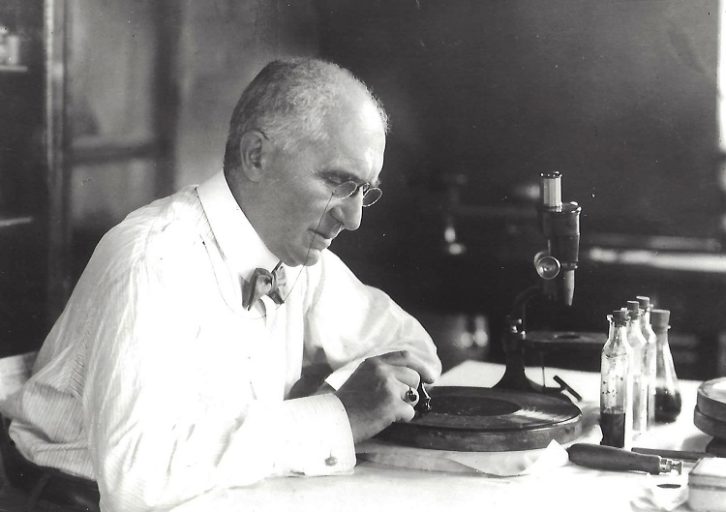

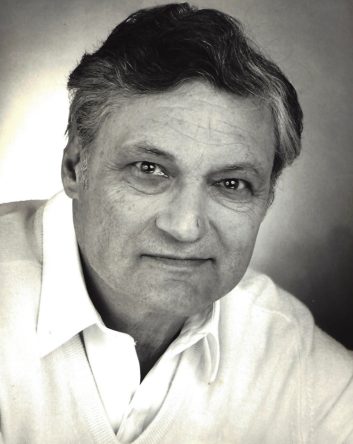

The disc record has also framed the life of one individual, Oliver Berliner, who at 91 probably knows more about the history of that invention than anyone else, because it was his grandfather Emile who invented it.

In the 1880s, Emile decided to improve the wax cylinder recording technology that Thomas Edison had developed a decade earlier. This led to the ubiquitous disc or “platter,” still revered by audio aficionados today.

However, this is not a story about Emile, but rather his grandson Oliver, whose father Edgar ran the Canadian branch of the Berliner Gramophone Company in Montreal at the time of his son’s birth.

Asked about memories of his grandfather, Oliver lamented that he had never met him.

“He died the same year I was born, 1929,” said Oliver, who admits to nothing in the way of memories about the operation his father ran. He was one year old when the rebranded U.S. parent recording and record producing operation, The Victor Talking Machine Company, was sold to the Radio Corporation of America, and the Berliners relocated from Canada to England.

“I believe that my father left RCA Victor of Canada on my birthday, May 29, 1930,” Oliver recalled.

Teenage entrepreneur

Although he didn’t spend his formative years hanging out in recording studios and recording pressing operations, Oliver eventually did his share of recording, acquiring a Presto recording lathe and cutting airchecks for none other than big band leader Xavier Cugat.

Berliner explained that his air-checking enterprise had its roots in an earlier venture where he provided “sound reinforcement” for dances at his high school. (After five years in the U.K. and a return back to Montreal, the family resettled in California, with Oliver ultimately enrolling at Beverly Hills High School.)

“In high school, I rented out portable PA systems for student dances,” he recalled. “Many of the clubs at Beverly Hills High had dances and I built up quite a reputation for providing these sound systems.

“I used Shure and Electro-Voice mics, as well as an RCA ‘Aeropressure’ dynamic mic. I built the amplifiers myself around 6L6s and 6SJ7s. The speaker enclosures were plywood bass reflexes fitted with Jensen 12-inch speakers.”

His reputation and rentals extended well beyond school dances, though.

“One of my clients was a Beverly Hills High graduate, the soon-to-be-famous André Previn,” he said. “As a teen, his trio was getting bookings in and around Beverly Hills, and André always called on me for a sound system.”

Following high school, Berliner enrolled in engineering studies at UCLA, but decided that this side of the recording business wasn’t really his passion.

“I soon switched to business administration with a specialty in marketing,” he said. “I graduated in 1951 with a BS degree.”

His association with Cugat and his band at about this time indirectly launched him into the next phase of his career in the music and recording industry.

“I was dating the daughter of Xavier Cugat’s drummer at the time,” Oliver said. “They were doing a lot of remote broadcasts then and that’s how I ended up cutting airchecks for Cugat. That’s also how I became interested in Cuban music.” (Cugat, a Spaniard, spent his early years in Cuba.)

“In 1956, I launched a music publishing business, Hall of Fame Music, which specialized in Cuban music. My company ultimately owned the two most famous cha-cha-chas in the world.”

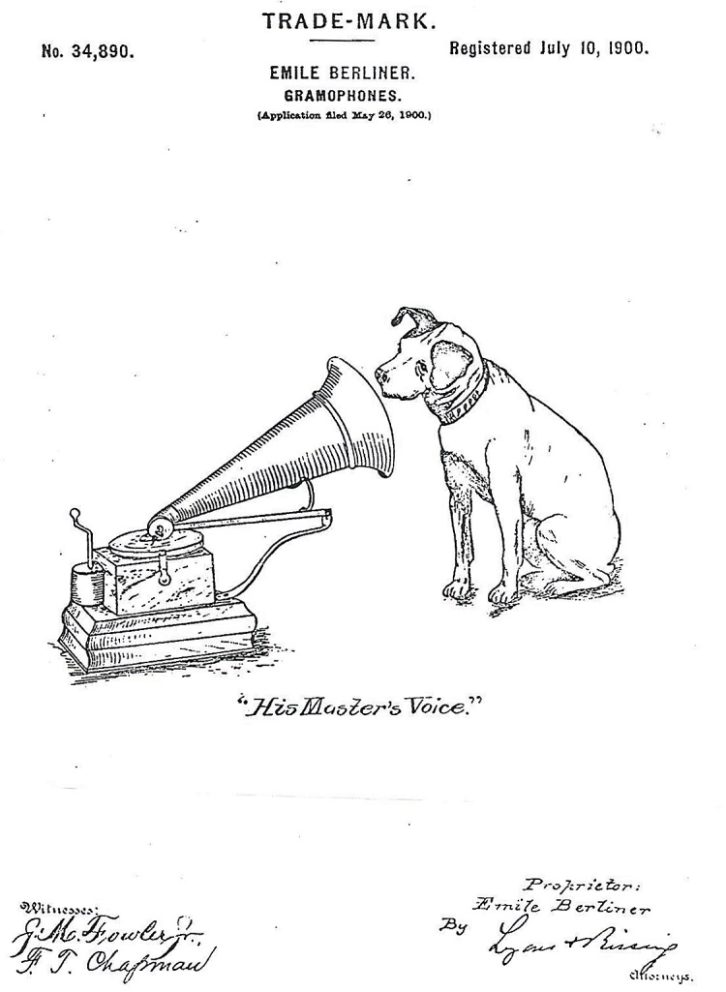

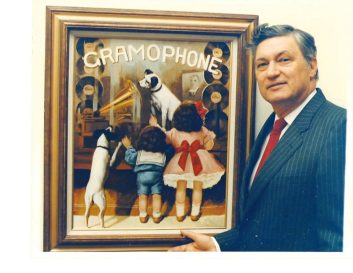

Oliver noted that during the time of his music publishing enterprise, he chartered a sister operation that he dubbed Gramophone Music Company.

“This was a way of keeping the name of my grandfather’s invention alive,” he explained. “That publishing company will live forever as an ASCAP member.”

Oliver’s next foray in businesses involving records was the 1965 purchase of an FM station in Orange County, Calif., which he recalled as a pioneering stereo operation.

After five years in broadcasting, Oliver turned innovator, creating what would ultimately be known as the “music video.” His concept was to make short video recordings of new artists that would be played in record stores as a way of providing exposure for these relatively unknown performers.

“I gave the idea to a record promotion friend at Warner Bros.,” said Oliver. “I suggested just recording the artist straight, without all of the crazy costumes and sets that were used later. I was hoping that Warner would hire me to produce these lip-synched recordings, as the soon-to-be-popular ‘music videos.’”

Broadcast product manufacturer

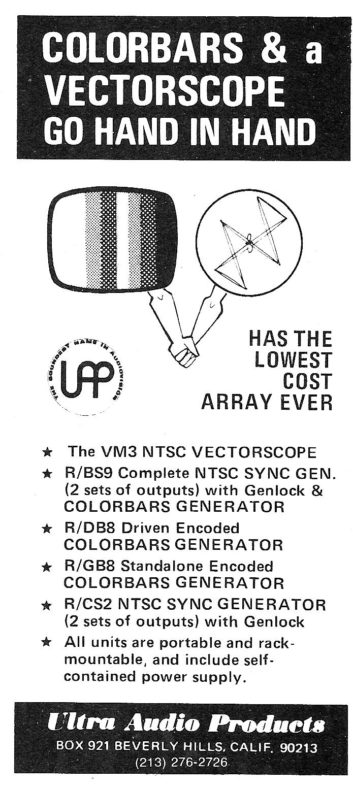

His next innovative effort was in the television field, even though the company was named Ultra Audio Products.

“We created low-cost compact versions of video test equipment — waveform and pulse-cross video monitors, and a vectorscope. These were designed for remote trucks, CATV studios, institutional operations; applications where users had limited space and money.”

Oliver’s creative efforts soon shifted to audio, with the creation of a compact consolette incorporating a rather unusual feature.

“It was intended to be run in a small TV production studio and had many features, including frequency-selective ducking,” said Oliver.

“When a disc jockey doing a voiceover hit the mic key, it ducked the level of the record he was playing by seven dB — not the entire audio range of the disc; just the voice range. The resulting effect of the voice enveloped by the music was astonishing. Radio should today be using it.”

In keeping with his music background, Oliver has been called as an expert witness to testify in several high-profile cases involving performance and usage rights.

When asked for his take on the current state of radio broadcasting, Oliver confessed that while he loved music, he was not an avid radio listener.

“I just don’t like what’s on radio today.”