Ed Czarnecki is senior director for strategy and government affairs at Digital Alert Systems and has served on numerous industry and emergency advisory committees, including with the FCC, DHS-FEMA, SBE, NCTA and others. He is currently chair of the ATSC TG3-10 working group on emergency alerts, and vice chair of the ATSC Advanced Emergency Information Implementation Team.

Radio World caught up with Czarnecki to learn about how the emergency alert system and broadcasters are handling the need to deploy critical COVID-19 and novel coronavirus information.

Radio World: We’ve heard a lot of discussion about the role of public alerting right now. U.S. broadcasters know the EAS and WEA systems; are these being used in the coronavirus crisis? How?

Ed Czarnecki: Public alert and warning systems are just starting to be used right now to keep the public informed about different aspects of this public health emergency. So far, we’ve seen WEA used more than EAS, with WEA notifications being issued in parts of Texas, Florida, California, Michigan, Rhode Island and elsewhere. Few EAS alerts have been sent so far, but it is possible that EAS will be used more frequently if this public health emergency continues to escalate.

RW: Which warnings specifically have come into play?

Czarnecki: A few jurisdictions have begun issuing advisories via WEA and even EAS.H EAS (and WEA) do not have specific event codes that directly relate to a pandemic or specific public health related alerts, so alert originators and broadcasters need to use generic messages like a Civil Emergency Message, or Local Area Emergency to cover those conditions (or a Public Safety Message for WEA).

One of the first COVID-19 related messages was a Civil Emergency Message (CEM) issued in Rhode Island on March 17. Their WEA message said: “State of RI: Due to COVID-19, do not gather in groups of 25+. www.health.ri.gov/covid.” For EAS, the message (if any broadcaster forwarded it) would have been the standard EAS header text for a CEM, followed by “This is a message from the State of Rhode Island. People should not gather in groups of 25 or more. Restaurants, bars and coffee shops are takeout or delivery only through March 30. All Rhode Islanders returning from international travel are required to self-quarantine for 14 days. Visit www.health.ri.gov/covid for more information.” The Rhode Island message is also an example of the CAP message being sent out with both English and Spanish messages.

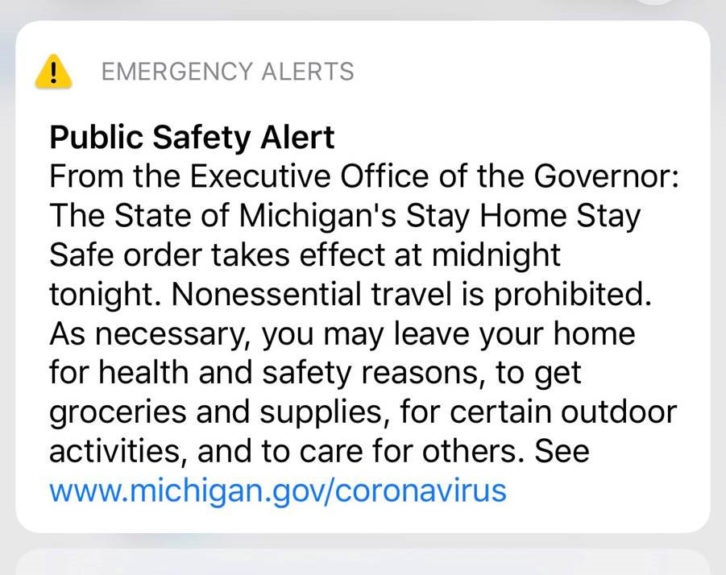

Other states, counties and cities have relied mainly on WEA, using the Public Safety Alert category for mobile alerts. New York City and El Paso, Texas, have sent out numerous city-wide WEA messages related to the coronavirus health emergency, so far. Michigan sent a state-wide WEA public safety alert on March 24, announcing that a “Stay at Home Stay Safe” order — prohibiting “nonessential” travel in Michigan, but telling people that you are allowed to leave your home for health and safety reasons, groceries and supplies, some outdoor activities and to care for others.

Manatee County in Florida sent out WEA public safety messages with the subject “coronavirus information” that read, “Prevent the spread of the coronavirus. Beach and restaurant restrictions in effect: 10 people per group, maintain 6 ft distance. Restaurant 50% capacity restrictions in place. Bars and nightclubs closed.” There are several other examples across the nation, all along the same lines. But, while relaying on WEA as a public warning channel, local authorities have tended to rely on broadcasters to relay broader public information about the public health emergency.

Michigan WEA alert:

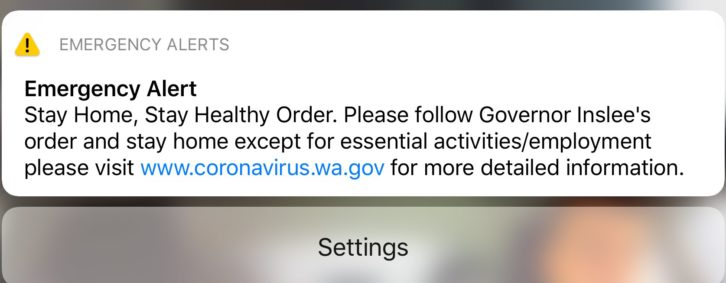

Washington state alert:

RW: Some experts worry about “over alerting.” What’s the right amount?

Czarnecki: This is a bit of a subjective question. In South Korea, the government was issuing a steady stream of messages to mobile phones (alerts, updates and advisories). While the info was initially appreciated initially, we hear that many Koreans became bothered fairly quickly by the stream of messages, tuning them out. Korean authorities might have gone a bit overboard, sending dozens of messages a day, each time a case was identified, each time a restaurant might have been exposed, etc. The government credits the mobile phone alerts to helping stem the spread of the disease, but we still hear anecdotal information about mobile users getting frustrated at the amount of messages they had been receiving (and whether it was relevant and important enough for them).

Alert originators should bear in mind a balance between keeping people informed, versus bombarding them and causing message fatigue.

Another point is to remember that these public warning systems — both EAS and WEA — are best used for targeted, actionable information. Not general advisories, but specific information telling people what to do.

RW: Why is it important to be aware of the difference between public information and a public alert?

Czarnecki: In some of the WEA message examples we just discussed, you can almost feel the struggle to squeeze emergency information into a system that was designed for concise emergency alerts. This challenge is relevant for both WEA and EAS.

Public alerts are a specific call to action, while public emergency information may be more general (e.g. health and care information about COVID-19). An alert should be targeted and actionable. It should concisely tell identify the risk (or situation), where (and when) it is located, what exactly people should do to maximize their safety, and how specifically they should do it.

[Read More: IPAWS Coronavirus Guidelines]

Public information tends to be the bigger story, a greater degree of information and instructions. More context, if you will. Emergency Public Information may be issued even though there is no “alert,” and EPI may also enhance an alert with more information on what is happening, what the response organization is doing, and what else the public should do for its safety.

The point here is that information needs to go through the right set of systems — the right tool for each type of job. EAS and WEA are best suited for that targeted, actionable alert and are not necessarily very good tools for conveying (or trying to squeeze) emergency public information into these relatively short message bursts.

When people receive an alert, they tend to seek additional information to make a decision — to confirm their understanding. And that usually means turning to radio, TV or internet news sites. This is the interrelationship between a public alert and public information — the alert is the “bell ringer” that drives people to seek additional information.

Alert and warning systems exist within a larger communication ecosystem. A public alert or warning about COVID-19 (or a stay-at-home/shelter in place alert) will serve to drive people to other communications media (broadcast, TV, cable, Internet) to seek out more emergency information. It may be a mistake to try to cram less actionable emergency information into an alert system — but it may be more effective to use alert tools to motivate people to seek out “the rest of the story” via media.

RW: What should broadcasters know or do right now that they’re not already doing?

Czarnecki: Broadcasters should ensure that their EAS equipment is in proper working order, and they should also check in with their LECC or SECC representatives to double check what event codes they should be enabling in case EAS is used for this public health emergency. This is also another reason why broadcasters should double check to make sure their software is up to date.

As I noted earlier, there is a real chance that the EAS system may be used by different jurisdictions, depending on what happens next with this public health emergency. It is important for broadcasters to double check that their systems are in proper working order, and up to date.

EAS operational readiness is essential — and this includes having the right event codes enabled for forwarding. If the originator is going to use a specific event code (like CEM, LAE, SPW or CDW), the receiver must be set up to handle it. The system fails if the originator uses an event code that a receiver is not configured to forward. In the DASDEC system, for example, the Alert Agent can be configured to be “open” to all sorts of event codes, but not necessarily fire off the alerts. It can essentially be configured to be “at the ready.”

Of course, broadcasters with newsroom operations are likely already in regular touch with local authorities, and that is a critical link for ensuring that emergency public information is being made available to the public. Local newsrooms are the nexus of the broadcasters’ role as an essential “first informer.”

RW: What should local alerting authorities do differently, if anything?

Czarnecki: Local authorities are challenged by this unprecedented situation. Their resources are being stretched in different directions. However, local authorities generally know best when emergency information is needed in their area and how best to communicate to people their jurisdiction.

We have seen in other situations overseas where medical professionals trained in risk communications had a measurable impact by releasing timely and effective messages for public awareness and other important information such as symptoms to look for. Clear, concise messages from authorities can help people (i.e. broadcaster audiences) feel more in control and persuade them to make important health-related decisions to help ensure their safety.

So, this leaves local authorities with the need to determine how much of that information should be sent via a public warning channel, like EAS or WEA, versus more general resources, like news stories and PSAs over broadcast media.

RW: You mentioned South Korea. What have other countries been doing?

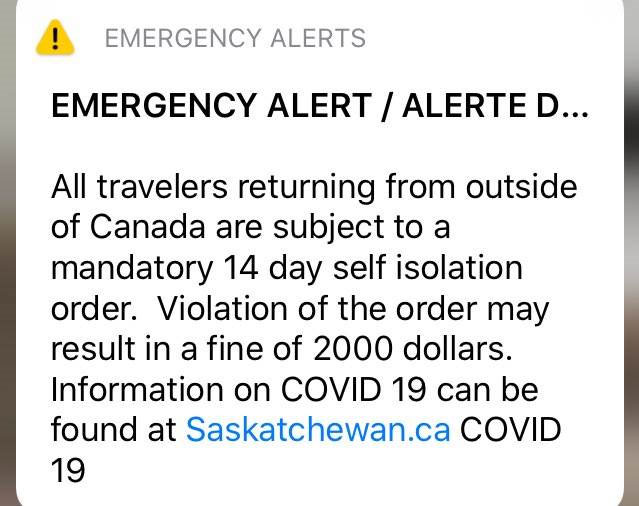

Czarnecki: We have information about how a few countries have been approaching public warning during this public health emergency. In Canada, one province (Saskatchewan) issued a Broadcast Immediate mobile alert to deliver a public information message (stay at home). We’re expecting other provinces to be issuing similar stay-at-home messages, and likely over broadcast media as well (via their version of the EAS system). Canada has an integrated public alert and warning system (NPAS) that is roughly analogous to the U.S. IPAWS system — with both mobile phone and broadcast components.

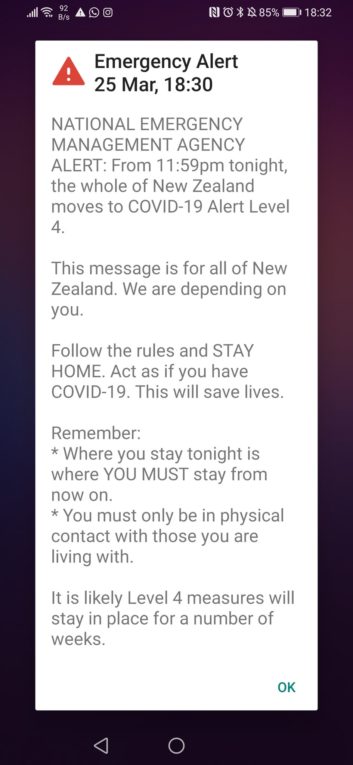

New Zealand also just launched nationwide COVID-19 alerts via text messaging, essentially telling the entire country to shelter-in-place. In New Zealand, the alerts are being transmitted over their cell broadcast system, with emergency information being disseminated over broadcast radio and TV.

New Zealand also just launched nationwide COVID-19 alerts via text messaging, essentially telling the entire country to shelter-in-place. In New Zealand, the alerts are being transmitted over their cell broadcast system, with emergency information being disseminated over broadcast radio and TV.

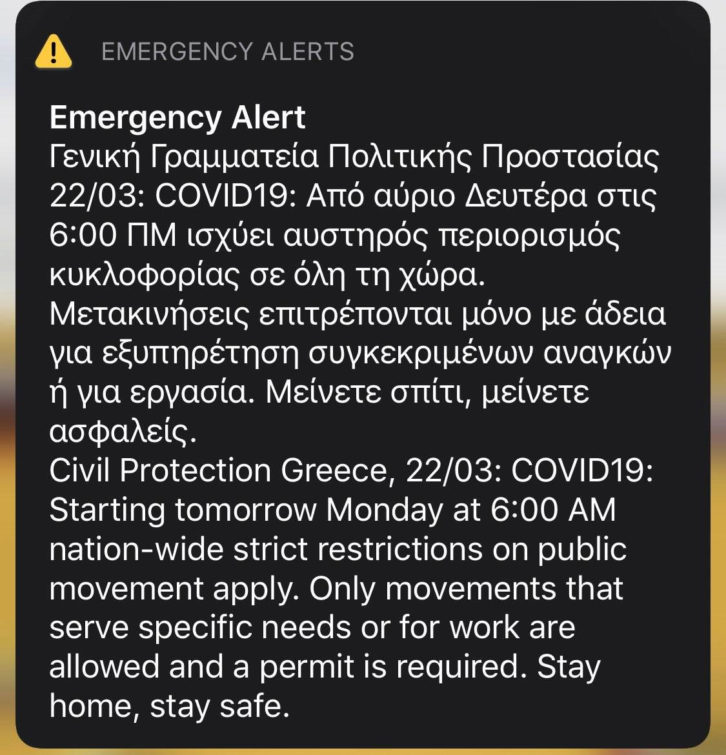

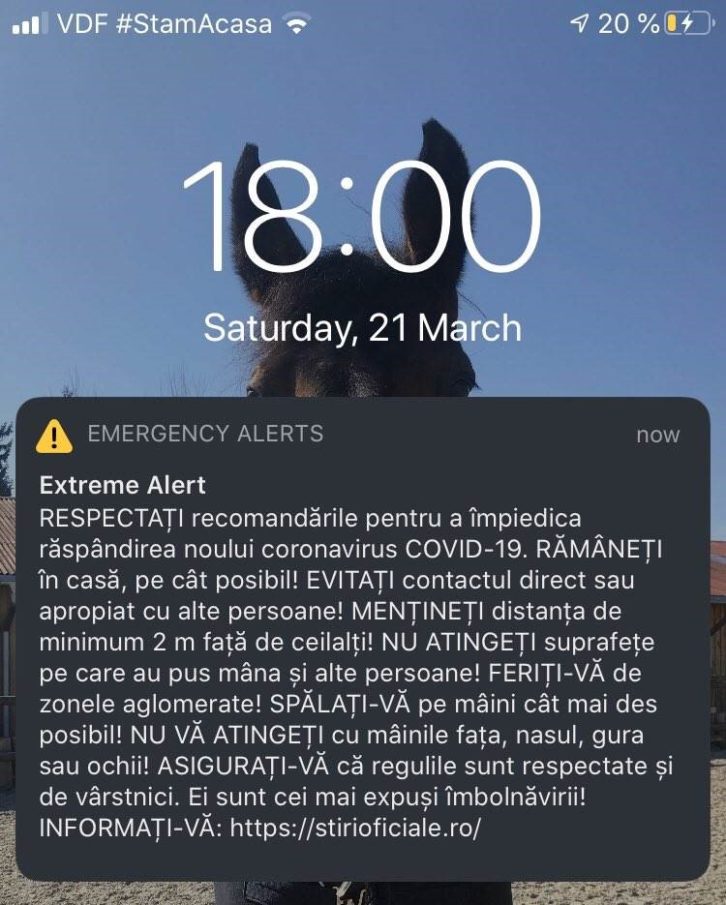

Back to public alerting, Britain, Denmark, Greece, the Netherlands, France, Denmark, Romania and many other European nations have sent social distancing and stay-at-home messages via text message alert. As far as I know, all these European countries have been relying primarily on mobile media to disseminate alerts, while relying on news media and PSAs to spread the word over broadcast media.

In the United Kingdom, the government issued a text message nationwide: “GOV.UK ALERT CORONAVIRUS New rules in force now: you must stay at home. More info and exemptions at gov.uk/coronavirus Stay at home. Protect the NHS. Save lives.” I believe this was the first use of mass mobile alert messaging by the UK government. The UK does not have a WEA-type system — the government asked the carriers directly to carry the message (and government agencies are now apparently infighting about who is in charge (or not in charge) of mass notification).

Interestingly (and perhaps disturbingly), the UK government is also in talks with mobile operators to use phone location and usage data to monitor whether people are actually staying at home or not (which has raised all manner of privacy considerations). Germany and Italy have also been evaluating this kind of mobile device location monitoring, which could include contact-tracing. I’m not opining on whether this is good or bad, or appropriate — just that different countries can have significantly different approaches to public warning and emergency information. And broadcasters tend to have a global role as a “first informer” even when there is no formal broadcast alert system in place.

Mobile alert in Saskatchewan:

Greek mobile alert (multilingual):

Mobile alert in Romania:

The Netherlands: