Ten years ago this week, Joe Pollet was a very busy man.

He is director of engineering at Entercom New Orleans and regional corporate engineer for Entercom Austin, Memphis and Wichita. Radio World checked in with him about what he and his colleagues did during and after Hurricane Katrina, which struck the Gulf Coast on Aug. 29, 2005. He also shares with us valuable lessons for any radio station that hopes to be prepared for emergencies.

RW: What is your most compelling personal memory from the storm and aftermath?

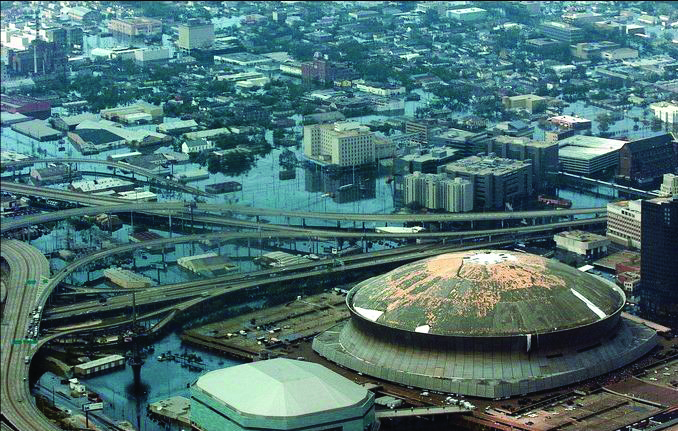

Pollet: Two days after Katrina, while still originating programming from our old studios adjacent to the Superdome, station management advised the assembled staff that anyone who wished to leave could and should do so before the flood waters rose any higher. Within 15 minutes of that announcement the station was virtually deserted with the exception of four people: the GM Phil Hoover, Oldies PD Andy Holt, Assistant CE Kevin Duplantis and myself.

In order to keep the station on the air, Andy assumed the responsibilities of call screener, Kevin operated the board and I became the on-air host introducing a never-ending stream of local government officials who were calling in providing emergency information to those remaining in and around the New Orleans area.

After what felt like an eternity, but was probably no more than an hour, a small entourage of dripping-wet staffers began returning to the station. These were the people who had tried to evacuate in vehicles that were too low to make it through the rising flood waters. Roughly 10 to 12 people returned, which enabled us to continue operating from that site for another 24 hours. Those who were able to make it out, mostly in high-rise trucks and large SUVs, regrouped 80 miles upriver in Baton Rouge. They met with what was then Clear Channel Baton Rouge officials and laid the ground work for what would almost overnight become the “United Broadcasters of New Orleans.”

The following day, Entercom corporate management, headed by Ken Beck and Marty Hadfield, arranged to have those of us who remained at the WWL studios evacuated via helicopter.

RW: The Houston Chronicle wrote then that “WWL(AM) 870, New Orleans’ oldest and most powerful radio station, has continued to broadcast since Hurricane Katrina struck. With a collapsed telephone system, no power and several television stations off the air, ‘The Big 870’ has tossed an information lifeline to a drowning city.” How was this possible?

Pollet: Our studios were equipped with a large new natural gas-powered generator. As fate would have it, natural gas was the only utility service in New Orleans that was not affected by Katrina’s passage. That generator continued to operate for almost a full month following Katrina. It eventually shut down with a “low coolant” alarm that was eventually found to be caused by a faulty sensor and not an actual problem.

In addition to being the state assigned “LP1” EAS station for South East Louisiana, WWL(AM) is also the federally assigned PEP station for the entire state of Louisiana. Under that designation, FEMA had equipped and stocked our transmitter site with a large 12,000 gallon diesel fuel tank. That large reserve fuel supply kept the AM transmitter operating on emergency power for one month following Katrina until commercial power was finally restored at that site.

Assistant Engineer Dominic Mitchum and I lived on cots in the basement of the nearby Jefferson Parish Emergency Operations Center for the duration of the event, keeping five of our six transmitters on the air under very adverse conditions.

RW: All told, which stations were involved?

Pollet: WWL(AM) was the primary “station,” however we were also simulcasting WWL’s programming on Entercom’s five other New Orleans-area stations. At that time the call letters were WLMG, WEZB, WKBU (now WWL-FM), WTKL (now WKBU) and WSMB (now WWWL, aka 3WL). Listeners were advised to tune to one of our other stations should the need arise.

RW: The hurricane focused the attention of U.S. radio technical managers on emergency preparedness, in a way that previous storms really didn’t seem to. Why do you think that’s the case?

Pollet: In my opinion, it was primarily due to the magnitude of the event and the continuous ongoing coverage by local, national and international media. It was virtually unescapable.

RW: Just a few months prior to Katrina, you gave a talk at the NAB Show called “Hurricane Preparedness in a City Below Sea Level.” So, how well prepared were you?

Pollet: Everything that was discussed in that April 2005 presentation factored into our ability to survive the storm. However, in my opinion, our pre-storm alliance with Jefferson Parish EOC Officials, Doctor Walter Maestri in particular, enabled us to maintain a broadcast presence and base of operations in the New Orleans area until we were able to restore functionality at our downtown studios well over one month post-Katrina.

RW: You’ve talked since then at more trade shows about lessons learned regarding communications, emergency plans, generators, fuel and so forth. What are the most important lessons for radio managers?

Pollet: Our biggest surprise, one day prior to Katrina’s arrival, was the unexpectedly large number of staff members who showed up at the studios offering to help in any way possible. Many, if not most, brought along a spouse, kids, parents and even dogs and cats. In reality, many were just seeking shelter from the storm without having to drive hundreds of miles in the mandatory evacuation process that was in effect. Many would probably later regret not evacuating when they still had the chance. This unexpected influx was obviously going to tax our small food supply far beyond its limit. In fact, the large number, estimated at more than 50 additional people, was probably the primary reason we were forced to evacuate what was an otherwise viable site several days after the storm.

We now have a strict emergency event participation policy in place. Staffers who agree in advance to stay during an emergency event must make other arrangements for the safety of family and pets. We’ve also learned that our previous emergency supply plans were woefully inadequate. Prior hurricanes were always one- or two-day events. Our supplies were based on that timeframe and consisted of little more than a few loaves of bread, an assortment of cold cuts and a few bags of assorted snacks. We now have enough MRE-style food on hand to last for at least one month. Drinking water is stored in advance as are water purification supplies. We slept in chairs or on the floor after Katrina. We now also have a large supply of air mattresses, portable showers and personal hygiene items on hand all sufficient for an event lasting at least one month.

RW: We also remember a lot of broadcasters pulling together to help one another that week. What do you remember about that?

Pollet: I received a surprisingly large number of calls from other New Orleans and Mississippi Gulf Coast Radio Broadcasters just prior to Katrina. All were requesting official permission to rebroadcast WWL. It became obvious that most owners, operators and their staffs were intending to evacuate the area for the duration.

Following the storm we also did what we could to assist in getting other stations back on the air. A large and unexpected supply of gasoline was delivered by engineers from the Entercom KC stations. After topping off the tanks in our surviving station vehicles, all remaining gasoline was delivered to a small Spanish-language station that was struggling to keep a balky gasoline powered generator operating.

RW: If you could go back to the moment the storm hit, is there anything you wish you’d done differently in hindsight?

Pollet: Several things come to mind, some of which are now considered “SOP” for emergency events.

Number 1 on the list is starting and switching to your emergency power generators prior to the storm’s arrival. Prior to Katrina, we would start and test operate all generators a day or so before an expected event. They would then be placed in “Auto” mode and eventually restart automatically when commercial power eventually failed, as it always does. Unfortunately that scenario does not take into account the many off-again, on-again commercial power events that can occur prior to a total outage. Each of those transitory events may contain, or be associated with, significant power surges and pulses — surges that can trip circuit breakers or blow fuses at a time when they might not be reachable until long after the storm subsides. We now manually start and switch to generator power in advance of any predictable sever weather event.

Number 2 would have been having a security presence, and additional food supplies, flown in by helicopter after Katrina passed instead of having the air staff and engineers flown out. In effect, we wound up abandoning what, at the time, was a working viable downtown studio site. Our outside on-air phone lines and ISDN codec lines were all still working. We also had one small but functional DSL-based Internet connection working.

Broken windows and doors prompted the security concerns, concerns that were augmented by the outbreaks of looting and general lawlessness. The 50+ people sheltered at the station made the food shortage issues obvious. However, both potential problems could have been remedied via helicopter resupply instead of evacuating from what was a prime functional location. Hindsight is indeed always 20/20!

For more on this topic, read our related story from 2005.