“When are you going to send me programming from your location?”

This question over the walkies from the station took us by surprise. We had in fact been sending signal from our remote over the RPU link for more than 20 minutes, or so we thought. At 6:40 the station had acknowledged our signal. Now it was almost show time, but no signal.

What had happened?

It was the 100th birthday of the Philadelphia Phillies baseball team. On this May night in 1983, we were behind home plate to broadcast the pregame ceremonies to mark the big occasion at Veterans Stadium.

Essentially we were isolated inside a chaotic house of 50,000 fans. Our connection with the station was via an antenna mounted on a 50-foot mast on our remote truck, out in the parking lot. A 500-foot umbilical cable connected us to the truck and transmitter.

Quickly it became obvious that the problem was “out there,” while we were “in here.” Being the only real tech type on this remote, I took off for the truck.

Security in the stadium was severe. I knew that it would take nearly an hour — way beyond the length of the show — to get out to the lot. So I took off following the direct route of the cable, coming eventually to a six-foot-high concrete wall with a chain-link fence on top, separating the stadium from the lot.

I vaulted to the top of the wall (this was in my younger days), swung over the fence, hung by my fingertips and dropped to ground on the opposite side. A quick dash to the truck and I was inside.

I realized that the power supply on the transmitter was dead. I needed about 24 volts of DC, and fast.

We had a little portable TV with a 24-volt battery tray on the bottom, but it was eight screws and two clip leads away.

Thus our whole broadcast hung on whether I had remembered to put my screwdrivers and clip leads back into my briefcase.

My life was contained in that black beauty, but in my controlled panic, I simply dumped it all on the truck floor. Blessedly, I found myself looking at the small Phillips screwdrivers and two clip leads sitting there atop the pile.

Like a whirling dervish, I took off the screws, bared the contacts and applied power to the transmitter just as the opening theme and sponsor credits ran out.

We made it, barely.

Sometimes the difference between success and failure in this business comes down to a single tool.

The Greeks knew

Socrates said you would know a craftsman by his tools. Plato said there is a tool for every task. These gems of wisdom were spoken nearly 2,500 years ago but remain true today.

To do your best work, you need a wide compass of proper and adequate tools in serviceable condition, and you have to be familiar with their use, limitations and operation.

Truly there is a tool for every task. My eight toolboxes are proof.

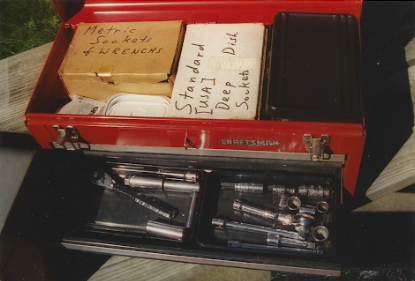

“Eight toolboxes?” you ask. Yes, and here they are, organized by function or type of use. In some cases, one must cluster certain tools to be effective.

Box 1 holds general tools. If I can only take one box, this is the one. Ninety percent of my work is done with this box. It includes small hand tools such as screwdrivers, Allen wrenches, a small drill, my electrician’s pouch and of course my trusty, fiberglass, 24-ounce, Craftsman hammer.

Box 2 holds light specialty tools such as a torpedo level, small punches, crimpers and riveter.

Box 3 is mainly for ratchets in three sizes: 1/4-, 3/8- and 1/2-inch, with cross-size adapters and related items.

Box 4 contains heavy specialty tools such as large wrenches and a 100-foot tape measure.

Box 5 is for extra-heavy tools including large pipe wrenches, 3/4-inch ratchets and large conduit punches and hole saws up to 2-inch. For any job that requires larger than 2-inch, we bring in the industrial electricians.

Box 6 holds video/RF tools including low-loss jumpers, my trusty Bird Wattmeter, five select elements and nearly 100 adapters. This is proof of Buc’s Cliché No. 1, “The Universe Is Divided Into Two Equal Parts: Connectors and Adapters.”

Box 7 contains audio and data tools — essentially the same as the RF box, but for audio. It includes a small audio oscillator and the invaluable CD put out by Ed Dulaney with every special audio sample you might want including touch tones.

Box 8 is for expensive, delicate stuff. This is where my digital voltmeter, inclinometer for satellite antenna adjustment and amprobe are kept. This box actually is a hard-shell makeup case. It may or may count as a toolbox, but it does a great job of protecting expensive items.

In addition to these, I have a few carry-ons including a 3/8-inch chuck, 14-volt cordless drill in its own carryall and an ancient carpenter’s box with woodworking tools such as a precision planer and an assortment of wood chisels.

At hand

Even if you are a master virtuoso with a tool, if you can’t locate it, it won’t help you. Keep your tools in a known spot. Replacing each in the same location as a matter of habit will reduce the chance of lost tools, a problem that can bring any project to a halt.

From my vast experience in construction, I can warranty that most master craftsmen are master artists. A peculiarity of artists is that their tools are organized “just so.” Exact personal organization is a strong trait that has been used as a plot device in murder mysteries, including Lord Peter Wimsey’s tale “Five Red Herrings.” Organize your boxes to save time, energy and frustration.

Mark your tools. Our work in broadcasting often takes place in collaborative environments. A few toolmakers dominate the industry (Sears Craftsman, Xcelite, Klein, Jensen and Snap-on) because of their quality and selection of product; so sometimes multiple copies of the same tool will be at hand in your work theater.

Buy several hundred name and address labels and paste them all over your tool boxes, test equipment and anything of yours that is worth more than the label. This practice causes misanthropes to think twice about stealing; and it’s good publicity for you. Etch your initials or ham call with your Dremel tool onto anything metal of value.

Scotch 33+ makes a great generic, quick-find marker. This versatile, durable electrical tape comes in a spectrum of colors. My personal tool color is super-hot red. My close associate, the exceptional engineer Bill Rosenfeldt, uses cool blue. Kevin Smith, a contract engineer in upstate New York and another regular construction partner, uses a minty, refreshing green.

When four or five of us work together, the tape on safety glasses, ear protectors, hardhats and ratchets makes the room look like one of those early, garish Technicolor movies minus the leading lady. At the end of the day, though, we get our tools back into the right boxes, ready for use another time.

Respect your tools and those of others. A favorite instructor at MIT once told us, “A tool is a machine that makes money. Everything else is a hobby.” He was right. Take good care of your tools and they’ll take good care of you.