Tom Hartnett is the technical director for Comrex.

Tom Hartnett is the technical director for Comrex.

This article appeared in Radio World’s “Trends in Codecs and STLs for 2020” ebook.

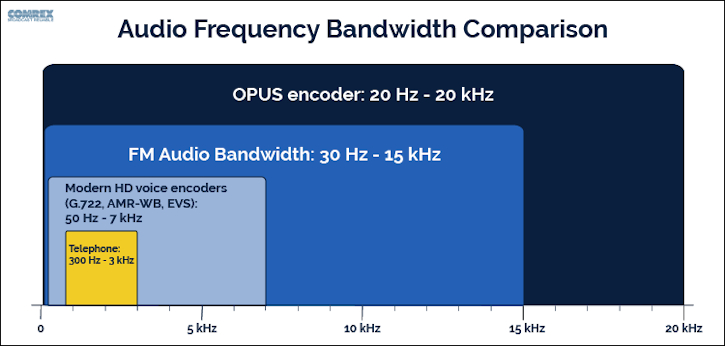

Despite being around for decades, FM broadcasting remains the most popular audio media around. A lot of the reason FM thrives, despite the attempts to create a “better” digital alternative, is technical. FM was defined with technical standards that deliver a low noise signal that allows for easy reception in most environments. But more than that, FM was defined as having deviation standards that allow for an audio bandwidth that covers the majority of the hearing spectrum. Sure, modern audio media bests FM in frequency response and signal-to-noise, but the fidelity of FM remains “good enough” for the vast majority of listeners. So much more than features like stereo imaging and dynamic range optimization, it’s the fidelity of FM that keeps listeners engaged. The ability to hear the funky bass line along with the high-hat cymbal, or the ability to derive the emotional nuances of a speaker’s voice is what makes FM radio shine.

But any broadcast airchain is only as strong as its weakest link. With digital recording and production, it’s relatively easy to make a great-sounding in-studio product. But generating live, remote audio has always come with its own set of challenges and costs. Too many times, broadcasters have been willing to compromise on the fidelity of remote feeds for the sake of cost and convenience, airing live audio from telephones. Telephone systems, by design, convey only the fraction of audio spectrum required for intelligibility. They filter out lows to avoid noise pickup, and they filter out highs for reasons having to do with the dated economics of 20th century digital telephony.

[Check Out More of Radio World’s Ebooks Here]

Comrex has built a company, and I’ve built a career, finding alternatives to live telephone audio for radio broadcasters. It doesn’t take any scientific studies or high-priced consultants to know that telephone audio is grungy, thin, and fatiguing to listen to at length. If the competitive challenge is to avoid listeners hitting the “next station” button, then maintaining listenable audio throughout your programming should be the primary goal. At the same time, it’s incredibly important that stations engage in their community (and monetize their brand) with remote broadcasting. Technology has helped combine these goals.

I’ll spare the reader a detailed history of this science, but a list of recent technology is helpful. Dedicated loops (when telephone tariffs reigned supreme), RPU radios, frequency extenders (maturing to multiphone line models), ISDN and POTS codecs each saw their era of popularity and utility wax, and each waned for their own reasons. Something new was always available that was more cost-effective or easier to procure. But the main objective — fidelity — was always either equaled or improved.

We all use IP pretty much exclusively for live out-of-studio audio these days, due to ubiquity and cost. And luckily, IP makes carrying higher fidelity audio feeds easy. Audio coding science has come a long way and implementations are now cheaper and lower power. Wireless IP has made the remote broadcaster’s dream a reality. It’s now possible to carry a handheld, battery powered device into the field, and generate programs that rival the sound of in-studio sources.

So game over, right? What could possibly come next? Problems remain to be solved. We still air telephone audio from listeners. Setting up a remote broadcast can still be a challenge for the nontechnical. And specialized audio encoding gear has significant cost.

Meanwhile, nonbroadcast industries have discovered that offering “toll quality” audio for communication isn’t good enough. Like broadcast, a competitive edge can be had by offering an experience with higher audio fidelity. The recent boom in video chat apps proves this point.

While audio challenges exist in that world with regard to echo cancellation and delay, fidelity has never been an issue. Developers saw early on that high-quality audio needs to be part of any system from the ground up. Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Teams, Messenger and Duo all use high-fidelity audio encoders.

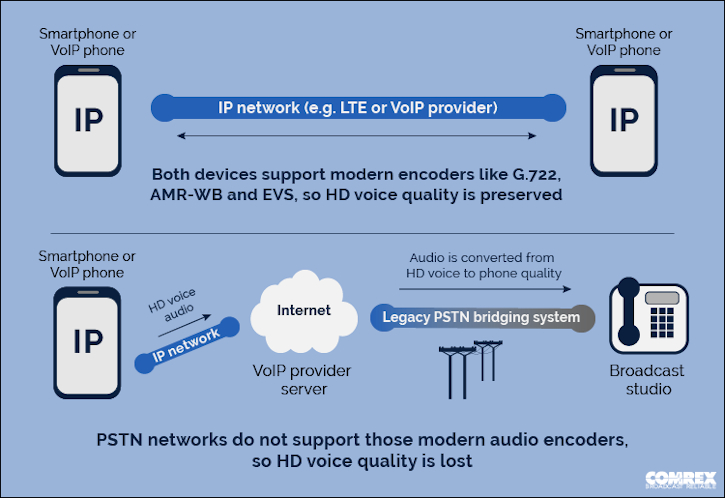

Voice-over-IP systems, now common in office environments, aren’t constrained by the legacy telephone system within their borders. They can by default deliver high-fidelity audio encoders when talking exclusively over their LANs. Even on a relatively poor audio system like a telephone handset the difference between an in-office call and out-of-office call can be startling.

This is because calls outside the LAN must convert the fidelity of the audio to the “lowest common denominator,” which is the legacy phone system.

Mobile phone audio quality is a long-time frustration for broadcast. For programming with listener call-ins, there’s been a routine need to disconnect callers who are unintelligible. This makes programs suffer and wastes valuable airtime. But even here, we see that the industry has realized there’s not always a need to stick with legacy low-fidelity audio.

As mobile phones and networks mature, it’s becoming increasingly common to experience high-fidelity “HD Voice” calls between mobile callers. Modern audio encoders like G.722, AMR-WB and EVS are integrated into late model phones, and the voice-over-LTE networks that support this traffic are quickly replacing the legacy networks. Several carriers are able to cross-connect high-fidelity calls between them, expanding the number of users who experience HD Voice on calls.

On VoIP and mobile networks the existing challenge is the same: there’s no easy way to “bridge the gap” and bring this high-fidelity audio into a broadcast studio reliably. So even when calls originate from these advanced networks, the caller audio is converted into the thin fatiguing sound we all know, in order to be compatible with legacy “bridging” systems.

So the next step in the evolution of high-fidelity remote audio for broadcast clearly involves finding a way to leverage existing systems into the studio. While that work is underway, there’s already one existing tool that can be used today to improve telephone audio: WebRTC.

When I first introduced this concept to broadcasters several years ago, it was a hard sell as it was difficult to describe in a concise sentence. But don’t be afraid of the scary technical-sounding name. WebRTC is essentially a video chat app that’s built into virtually every web browser, whether desktop or mobile. It’s an open standard and allows anyone to create a video chat service without requiring any software installation on the participant’s system. That’s because the critical pieces are already in the browser, waiting to be “woken up.”

Like other video conferencing apps, WebRTC uses a high-fidelity audio encoder by default. This encoder is called Opus, and it’s becoming the de facto standard for live web conferencing.

Because WebRTC doesn’t require the video part of a call, every web browser, both desktop and mobile, can now be considered a high-fidelity audio encoder using Opus.

Using WebRTC can be as simple as subscribing to an audio-only service provider like ipDTL, Cleanfeed, or SourceConnect Now. This will require a pro-grade audio-ready computer at each end of the link. The Comrex Opal provides a pro-grade hardware solution that handles all the complexity within its server box.

Either way, by using WebRTC you’re leveraging the power of developments that were never intended to be used for broadcast. This is the way things have been done for decades — from POTS codecs, ISDN to IP, broadcast always finds a way to leverage new developments for their unique requirements.

We’ll continue to do that as existing “HD Voice” networks converge and interoperate. Maybe someday soon the goal of banishing telephones from the radio will come to pass.