Mohammad Sharif Walid, BBC World Service presenter,

in the studio. Courtesy Mohammad Sharif Walid

OTTAWA, Ontario — With the advent of radio in the 20th century, the shortwave band (1710–30,000 kHz) soon became a hotbed of long-distance radio broadcasting. Used primarily by state-run international broadcasters, plus ham radio operators and ship-to-shore radio communications, the shortwave band was prized due to its astoundingly broad reach.

That reach was — and is still — made possible by the tendency of ground-based shortwave radio transmissions to bounce off the ionosphere and back to earth; allowing shortwave broadcasts to “hop” repeatedly, increasing a broadcast’s range while minimizing its decay. This writer once heard BBC World Service on 6175 kHz coming to him from both directions at once; a phenomenon proven by the “echo” he heard caused by the “around the world” shortwave signal arriving at his receiver slightly later than the “direct path” signal.

At the height of the Cold War, the shortwave bands were packed with content as the Voice of America and West Germany’s Deutsche Welle (Voice of Germany) traded ideological punches with Radio Moscow and East Germany’s Radio Berlin International. This is because analog shortwave radio broadcasting was the only way for both sides to make their political cases cross international borders: There was no satellite TV, let alone any internet.

Fast forward to 2016. Today, shortwave and its often scratchy, interference-ridden, fading mono transmissions have been trumped by other higher-performing, content-rich delivery platforms. As a result, “A large part of the audience that would formerly listen to international broadcasters can now get the same information from websites and/or satellite TV,” said Andy Sennitt, former editor of the World Radio Television Handbook and shortwave correspondent with the now defunct Radio Netherlands International radio service. “The regular audiences in Europe, North America and parts of Asia are now a tiny fraction of what they once were,” Sennitt noted. “In parts of Africa and South Asia there are still significant shortwave audiences, but even those are gradually declining.”

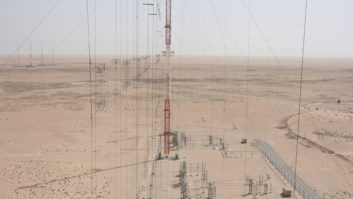

At the same time, Western broadcasters such as the BBC World Service and others have found it cheaper to distribute their content to domestic FM broadcasters in target countries, as well as by satellite TV and the web. Add the end of the Cold War (or at least the first one) with fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and cash-strapped Western governments no longer see a reason to spend millions operating 100 kW shortwave transmitters and their attendant large antenna farms.

This is why the BBC World Service, Voice of America, and others have substantially reduced their international shortwave broadcasts, with the former going as far as ending transmissions to North America, Europe, and Australia and parts of Asia. Meanwhile, once popular Western shortwave broadcasters such as Radio Canada International, Radio Netherlands, Swiss Radio International, and Radio Sweden International ceased shortwave broadcasts altogether. Some of the former shortwave stations now stream their content on the web.

“In the past 10 years, the majority of legacy government-sponsored shortwave radio stations have either closed down or dramatically reduced their services,” observed Thomas Witherspoon, editor of the popular shortwave news site SWLingPost.com. “Very few shortwave broadcasters still target North America and Europe.”

SAME USAGE, CHANGING PLAYERS

Given the reduction and/or demise of so many international shortwave broadcasters, one might expect that the world’s shortwave spectrum would be far quieter in 2016. But this is not the case. Based on recent data compiled by the High Frequency Coordination Conference, the International Telecommunications Union committee that coordinates the allocation of specific shortwave frequencies among nations, “There is about as much broadcast activity on the shortwave band today as there was in the past,” said Nigel Fry, head of Distribution for the BBC World Service Group.

Thomas Witherspoon, editor of www.SWL.com, in his

radio listening room. Courtesy Thomas Witherspoon

“What has changed is who is using the band. As once-dominant Western broadcasters have scaled back or shut down their transmissions, others have taken their place, particularly by taking over the frequencies that are most effective at reaching large parts of the globe reliably and relatively clearly. Meanwhile, in those areas where shortwave remains the best way to reach people — such as in Africa and parts of Asia — the BBC World Service and other broadcasters are still relying on it.”

A case in point: The BBC World Service’s 5975 and 6175 kHz frequencies — once the foundation of the BBC World Service’s evening service to North America — is now being used by China Radio International and the Voice of Vietnam. Radio Netherlands’ one-time popular 6165 kHz North American channel is now being used by Radio Havana Cuba.

When it comes to state-run shortwave broadcasters today, “by far the most dominant is China Radio International,” said Sennitt. “Soft power [e .g. wooing international listeners to a given state-run broadcaster’s political position] is being used by the Chinese much more effectively than by any other nation. They also use satellite TV and, in some countries, domestic radio. In the U.S. there are a number of stations owned by Chinese companies in major cities, even Washington. China Radio International is carried on these stations for all or part of the time. But their audience is minuscule,” he said.

The 1976 Panasonic RF-2200, the model of shortwave radio

used by the author. Courtesy www.swl.com

As well, much of shortwave’s relinquished bandwidth has been taken up by donation-funded religious radio stations, plus private broadcasters. In the second category, “WRMI is the first station that comes to mind. This U.S. station experienced a significant expansion in late 2013,” said Witherspoon. “After WRMI purchased the [former] WYFR transmission site [in Okeechobee, Florida], they thought they would begin with one or two transmitters on the air and perhaps expand slowly. But at last report WRMI general manager Jeff White told me they now have all 14 of their transmitters on the air, most up to 24 hours a day.” WRMI makes its living by renting airtime to third-party religious, political, and state broadcasters.

Meanwhile, shortwave’s ability to cover large areas economically (if not with great audio quality) makes it a natural for Third World countries. For example, South Sudan has recently added shortwave to complement it Eye Radio FM broadcasts. The shortwave broadcast, which began April 26, covers “the whole of South Sudan including remote areas in which communities are not able to access FM radio stations,” said Stephen Omiri, CEO of Eye Media, Eye Radio’s parent company.

“KVOH in Los Angeles — a Christian broadcaster known the Voice of Hope — has recently put the Christian Vision shortwave station in Zambia back on the air,” added Witherspoon. “I also learned from Radio World that World Christian Broadcasting launched its second shortwave station, Madagascar World Voice, in late March.”

As well, according to Fry, the BBC is planning to start broadcasts to Ethiopia and North Korea this fall. “So some regions that especially need the service shortwave provides will be receiving it, at least in some measure,” Witherspoon said.

“Another expansion involves low-power (10 kW or less) shortwave broadcasters in Europe, particularly in Germany,” said Kim Andrew Elliott, audience research analyst with the Voice of America. “Examples include Channel 292 on 6070 kHz, and Radio 700 on 3985, 6005, and 7310 kHz. They are like LPFM in the United States, except the European low-power shortwave stations can sell time and have very low rates. This encourages participation by niche program makers. Other low-powered shortwave stations in Europe are not licensed, i.e. they are pirates. Most are found on frequencies just above 6200 kHz.”

India’s Avion AV-DR-1401 DRM Portable Radio.

Courtesy Avion Electronics

DIGITAL SHORTWAVE RADIO

The local/regional push to bring digital radio to the MW (AM) and FM broadcast bands through DAB and (in the U.S.) HD Radio does have an all-band (including shortwave) counterpart. Known as Digital Radio Mondiale and operated in test broadcast mode for many years by numerous shortwave broadcasters, DRM “offers an excellent option for delivering the great advantages of long-distance, wide-coverage shortwave broadcasting in excellent audio quality with extra features and multimedia data,” said Ruxandra Obreja, chairman of the DRM Consortium, an international group driving DRM’s worldwide campaign for deployment.

Even in its current test mode, “about half of the world population is within range of a DRM signal,” Obreja noted. “BBC, All India Radio, Radio Vatican, Voice of Nigeria, RNZI, and Radio Romania are regularly broadcasting in DRM shortwave,” she said. “The value of these services is beyond any doubt. What they need is receivers or receiver solutions.”

Fortunately for DRM, All India Radio’s decision to update its shortwave and MW analog transmitters to DRM digital transmission is giving this format the big push the consortium has been hoping for. The 1.25 billion people living in India is large enough “to support indigenous DRM radio receiver production; both portables and in-car units,” said the BBC’s Fry.

“This is creating a product base of DRM radios that can be sold into other countries, should they decide to embrace DRM.” The made-in-India Avion stereo portable DRM radio — known as the AV-DR-2401 — was shown at IBC2015 and is available for purchase at www.avionelectronics.in for US$189.

“There are rumors in the DRM community that a Chinese manufacturer is plotting to release a DRM portable by end of 2016,” said Witherspoon. “This might make sense as there could potentially be a substantial market in India if the receivers are effective and affordable.”

Conventional radio broadcasting isn’t the only possible use for DRM. For instance, the German navy is using DRM to deliver audio, video and data to its ships and personnel around the world,” said Obreja. “The U.S. Coast Guard is also considering using DRM in the same way for services to the far north.” Meanwhile, Radio New Zealand is using DRM to backhaul audio content to the Pacific Islands, “where the digitized programs are reconverted to FM” for conventional analog transmission, she said.

Digital images transmitted by analog shortwave

and captured in the U.K. from the VOA Radiogram program.

Courtesy Kim Andrew Elliott

However, Sennitt is skeptical that DRM will be able to leverage its India deployment to global success. “If you believe the DRM Consortium, it’s just a matter of time (until this occurs). But they have been saying that for well over a decade,” Sennitt told RWI. “In my opinion, DRM is now a niche technology that was devised 10 years too late. The major receiver manufacturers have ignored it, and the few radios that have been produced in small quantities were too expensive and performed poorly. So there’s absolutely no consumer demand. Only a tiny proportion of shortwave transmissions use DRM, and most shortwave listeners can’t receive them.”

Perhaps DRM’s ongoing rise to prominence in India will change this situation globally; perhaps not. In the meantime, the Voice of America is running its own digital transmission tests over analog shortwave, on the “VOA Radiogram” show hosted by VOA’s Kim Andrew Elliott. In this program Elliott — one of shortwave’s most respected researchers/broadcasters — sends out digital images and text to listeners. To decipher these broadcasts, each listener must have a shortwave radio with an audio connection to a PC loaded with decoding software such as Fldigi, MixW, MultiPSK, or DM780.

“Kim Andrew Elliott has amassed a sizable audience of listeners around the world who decode his mostly digital broadcasts which originate at the Edward R. Murrow transmitter site in Greenville, North Carolina,” said Witherspoon. “Elliott regularly receives (proof of) decoded images and text files from across the globe, and it’s important to note that his transmissions can more easily penetrate jamming than analog AM broadcasts.”

Equipment used by a shortwave listener in Luxembourg

to receive and translated VOA Radiogram’s digital images,

sent by analog shortwave. Courtesy Kim Andrew Elliott

According to Elliott, his VOA Radiogram digital text/image transmissions have proven that such information “can be broadcast by any shortwave transmitter, with no need for modification, and received on any shortwave radio, even inexpensive portables with no single sideband capability,” he said. “We have found that text is received successfully in conditions where an analog voice broadcast would be difficult to understand. So while DRM reduces the capability of shortwave, digital modes via analog radio actually extends the capability of shortwave.”

LONG-TERM VIEW

Type “Is shortwave dead?” into Google, and you will receive pages of websites arguing on both sides of the issue. The reason this is such a contentious question is due to the demise of Western shortwave broadcasters and their broadcasts to North America and Europe. The end of these broadcasts disenchanted many formerly avid shortwave fans (including this writer), causing them to mourn the loss of what had been an interesting and challenging listening hobby and look elsewhere for diversion.

Broadcasters Who Have Left Shortwave or Reduced Content Since 2006 According to VOA’s Kim Andrew Elliott, the following international broadcasters have left shortwave or reduced their output since 2006:

Deutsche Welle (Germany)

FEBC Saipan

HCJB in Ecuador (except for low power domestic shortwave)

Internacional of Portugal

International Radio Serbia

Kol Israel

Radio Austria International

Radio Belgium, shortwave from the French and Dutch language broadcasters in Belgium

Radio Budapest

Radio Bulgaria

Radio Canada International

Radio Exterior de Espana relay in Costa Rica

Radio Netherlands

Radio Polonia

Radio Prague

Radio Singapore International

Radio Slovakia International

Radio Sweden

Radio Tashkent (Uzbekistan)

Radio Ukraine International

RAI International (Italy)

RDP

Vatican Radio

Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

Voice of Russia (formerly Radio Moscow)

Voz Cristiana (Chile) That said, the research that went into this article suggests that the shortwave band is sufficiently alive to be still evolving. The retreat of the BBC World Service and other Western broadcasters from the band has left space for other countries and private companies to grab their frequencies, while DRM’s win in India has given this digital shortwave format its first credible chance at going global.

But does this evolution mean that shortwave has a future? On this crucial point, the experts disagree.

On the positive side, “shortwave remains the most accessible international communications medium that still provides listeners with the protection of complete anonymity,” said Witherspoon. “I still see a place for shortwave in the 21st century, especially for reaching areas of the world that are prone to natural disasters that destroy local broadcasting and Internet infrastructure,” added Fry.

On the negative, “shortwave is a legacy technology, which is expensive and environmentally unfriendly,” said Sennitt. “A few countries are hanging on to it, but most have faced up to the fact that the glory days of shortwave have gone. Religious broadcasters will still use it because they are not too concerned with listening figures,” he said.

“China Radio International, I am reliably informed by someone who worked there, gets a huge budget and has not so far been under any pressure to cut costs, but as growth in the Chinese economy starts to slow down it will be interesting to see how long this situation continues; especially given the other soft propaganda platforms already used by the Chinese.”

So what will happen to shortwave in the years ahead? The only reasonable advice is — stay tuned!

James Careless reports on the industry for Radio World from Ottawa, Ontario.