It’s the sign of a good engineer to design facilities with backup systems.

We all know it’s just a matter of time before the “main” whatever will fail, requiring full dependence on the backup gear.

But don’t be lulled into a sense of false security just because you have a backup — whatever it may be. For best reliability, these backup systems need to be tested periodically.

[Check Out More of Workbench Here]

In the old days many of us performed Sunday night maintenance, from midnight to 6 a.m., during which studios and transmitters were cleaned, and backup systems were tested on the air. Few of today’s broadcast engineers have that luxury, yet the backups still need testing to ensure reliability.

Case in point, a backup RF amplifier. For the purposes of this column, it was a 500-watt backup RF amplifier drawer that sat on a shelf at the transmitter site until it was needed in an emergency. Fortunately, a wise engineer decided to check out the relic. When it didn’t fire up, he sent it to a nearby contract engineer for repairs.

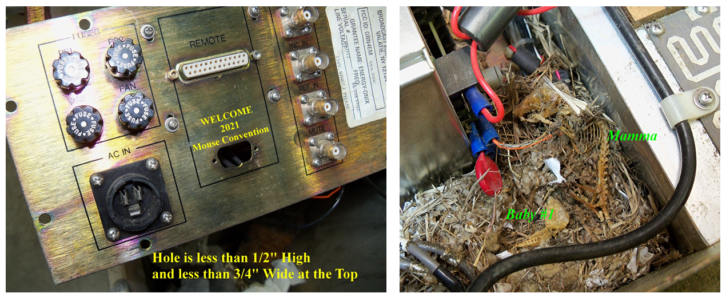

Fig. 2: The skeletonized remains of a mature mouse and baby are visible among the litter. (right)

The first clue was a missing Sub-D connector on the rear panel. This hole was factory-punched, and not a modification. But perhaps a hole for an option that should have been covered — it was not. The missing connector left about a half-inch hole as seen in the first image. The text label gives you some idea of what was awaiting the engineer investigating the unit.

The second image shows the nest and mess that field mice made of the inside. What is amazing is that after opening the top of the transmitter, the contract engineer inspected the top, bottom and sides carefully to see if there was any other way in. There was not. So, takeaway No. 1 is that mice don’t need more than a half inch, and maybe less, to infest our gear.

The top was replaced and the contract engineer developed a cleaning plan, starting with purchasing a high-filtration full-face mask. Mouse urine, feces and litter can harbor dangerous (and possibly deadly) bacteria — mice are filthy animals. Because of the contamination hazard, do not use a vacuum to suction the debris; its exhaust will only contaminate the air and your shop.

This job called for several toothbrushes, wooden cotton applicators, Clorox or similar brand wipes, and bottles of at least 70% denatured alcohol, along with latex gloves. A large plastic trash bag was placed on the workbench and the amplifier was placed inside. The bag edges were folded up around the equipment to prevent any liquids from contaminating the workbench. The oversize bag also provided room to discard waste as it was removed, lessening the chance that the discarded debris would miss a garbage can.

Using a combination of wooden cotton applicators saturated in alcohol, needle-nose pliers (for removing larger pieces of debris), and the wipes, the painstakingly slow job of removing the nesting materials, feces and mouse skeletons began.

Yes, apparently both the momma mouse and two offspring died inside the equipment. In one of the accompanying photos (Fig. 2) you can see the spines, ribs and skulls of momma and one of the offspring.

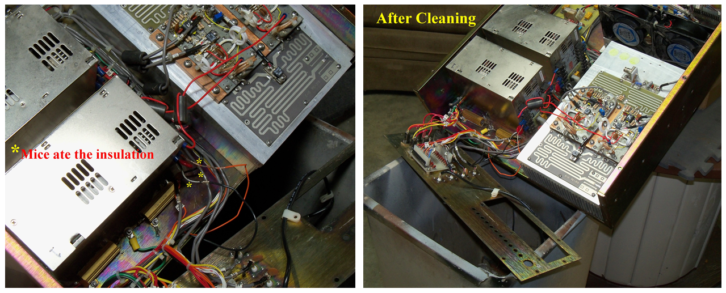

Fig. 4: The cleaning is complete. (right)

In addition to using the chassis as a toilet, the mice chewed the insulation off several wires. The missing insulation can be seen on the red wire in the third image (Fig. 3). As a part of the repairs, the damaged wires needed to be replaced. Cable ties that secured bundles of wires had to be cut; the wires separated, and individually cleaned. The cleaning process was tediously slow, to avoid creating any airborne dust, while thoroughly cleaning.

After scrubbing with the swabs and toothbrush, and saturating the boards with the alcohol, the chassis was moved to a clean trash bag and left for 48 hours so all liquid cleaning fluids evaporated. If you’re doing work like this, seal the used bag with cable ties and dispose. Do NOT compress the bag as you seal it — the escaping air may have the bacteria you are trying to avoid.

The fourth image (Fig. 4) shows the sanitized unit. To complete the cleaning, the rear panel was dismounted from the enclosure, showing the “innards” of the RF amplifier. Note that the large aluminum heat sink to which the RF combiner circuit card is mounted (with the squiggly lines) made its way back to shining once again.

So inspect your backup gear — and especially any welcome holes, no matter how small.

John Bisset, has CPBE, more than 50 years in broadcasting and is in his 31st year writing Workbench. He handles western U.S. radio sales for the Telos Alliance and is a past recipient of the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award. Workbench submissions are encouraged and qualify for SBE recertification credit. Email [email protected].