Hobbyists who listen for distant signals often face a dilemma. The best places to hear distant “DX” signals are in remote and rural areas that are free of electrical interference. Unfortunately, many of us live in urban areas where there is lots of noise. If you reside in an apartment, for example, there is no place to string large antennas.

SDRplay’s new nRSP-ST software-defined radio, which retails for $499, is a clever prosumer solution to this problem. It combines an SDRplay RSPdx-R2 general coverage radio receiver with a Raspberry Pi computer, contained in a low-profile black metal case. The unit is designed to accept up to three antenna inputs.

The game changer is its built-in web-server, which allows it to connect to the internet or LAN via Ethernet or Wi-Fi. Afterward, you’re able to access it via a URL in a web browser. It’s compatible with nearly any browser and can be used on Android or iOS devices.

Like the RSPdx-R2 on which it is based, the nRSP-ST covers from 1 kHz to 2 GHz and supports up to 10 MHz of spectrum sampling in one session. The unit can also be controlled with SDRplay’s free software control program, SDRConnect, either over your home LAN or conventionally with a direct USB cable. But it is the remote connectivity that makes the nRSP-ST incredibly useful from a radio geek’s standpoint.

For purposes of this article, I installed the nRSP-ST in the second-floor “radio room” at my home in Ottawa, Canada; you may recall a photo of the room in my 2024 article about SDR. With the unit connected to my home network, I am able to scan for DX signals from the convenience of my first-floor home office.

A real need

SDRplay, a U.K.-based manufacturer, was thinking big when they designed the nRSP-ST.

“A lot of people — particularly with the demographic of our customers — are getting older and less mobile,” said Jon Hudson, co-founder of SDRplay.

“They are downsizing by moving to smaller premises like apartments or HOAs where they can’t really get antennas erected.” Hudson noted these are typically noisy environments that hamper reception of distant radio stations, which are often weak in signal strength.

“Add in the fact that there is a growing hobbyist interest in networking radio receivers and operating them from a distance, and all the factors came together to motivate us to create the RSP-ST,” Hudson said.

The nRSP-ST is very much a “set it and forget it” type of technology to install. Once its drivers are downloaded and the nRSP-ST is connected to a network, it runs trouble-free. This includes recovering after power blackouts.

Tying into SDRPlay’s intended use case, it is entirely possible for an nRSP-ST owner to install this unit at a remote, electrically-quiet location they have access to — a rural home, a friend’s house in the country or even a remote research station — and connect to it from their home computer in the city. Users can also share access to their nRSP-ST with other people in the world over the web.

There are limitations to consider. Like any radio, the nRSP-ST must be connected to an external antenna. Fortunately, the SDR has ports for up to three, which the remote user can switch between on their computer using a mouse.

For control and audio with low latency, the nRSP-ST will need access to broadband internet service. These days, that should not be much of a problem.

In action

One of the attractions of SDRs is the ability to record large amounts of data to IQ files. The nRSP-ST offers that capability to record and play back IQ files remotely, provided there is enough storage on the device where it is connected. It also affords the ability to record IQ and audio files to a NAS network device, if available. As I mentioned, it can record up to 10 MHz of spectrum in a session, though some users have reported it receiving better using just 2 MHz of spectrum.

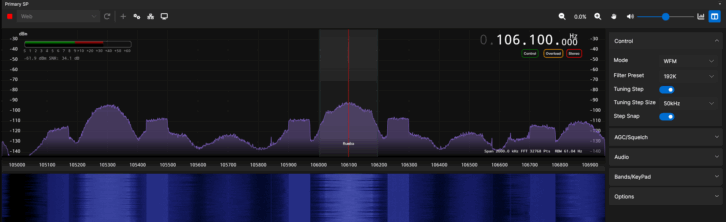

In my explainer article last year I detailed what it’s like to use a directly connected receiver to a computer. Essentially, controlling an SDR on a home computer is like operating any web-based click-and-point program.

When accessing a networked nRSP-ST over the web, the only difference is you will need to enter in its IP address and port, by default port 9001, in your web browser. To facilitate control over the internet, you’ll need to give access to the port to the outside world in your home router.

While I listen to signals with an SDR, I often use the World Radio TV Handbook app, which I’ve previously reviewed for Radio World, to determine where the stations I am receiving in Ottawa are located. I will also listen to a station’s online stream to compare it against what I’m hearing over the air. The combination of the nRSP-ST, online streams and the WRTH app make identifying international shortwave radio broadcasts a pleasure.

As you’ll observe in the photos, the ability to toggle between my MLA-30+ 100 kHz–30 MHz loop antenna, which is Antenna A on the SDR, and the 100-foot longwire I installed in my attic two decades ago when my house was being built, Antenna B, is a great feature.

Depending on propagation conditions in the ionosphere and electrical noise, I can select the antenna that makes the most sense for hearing the signal I desire. In this case, I was tuned to Jeff White’s WRMI Radio Miami International transmitting from Okeechobee, Fla., on 15700 kHz at 12 p.m. ET.

The MLA-30+ has higher gain than my homebuilt longwire but it comes at a cost. A higher noise floor can drown out weaker signals that my less sensitive longwire can manage to receive. As a result, I now have far more flexibility for ferreting weak signals, which I can commonly receive from Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. Higher gain isn’t always better gain. That’s something I did not know until I was able to switch between antennas in real time.

Given my experience testing SDRplay’s nRSP-ST, I can say this is a radio worth owning, even if you don’t intend to set it up remotely in the far North of Canada. In fact, if I could only own one general coverage radio receiver, and I own quite a few of them, the nRSP-ST would be my choice.

So where can you buy this radio? SDRplay sells the nRSP-ST directly through its website and it is available through several retailers. Don’t be surprised, however, if you have to wait a while to get yours. “We’re only an eight-person company,” Hudson told Radio World, “and there’s a lot of people wanting to buy the nRSP-ST.”

[Sign Up for Radio World’s SmartBrief Newsletter]