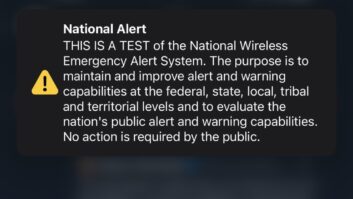

In November 2011, the Federal Emergency Management Agency initiated the first nationwide test of the Emergency Alert System. A subsequent report of the test results demonstrated that, while the system was fundamentally sound, there were some necessary corrections in order to maximize the distribution of the alert while minimizing public confusion.

In June of this year, the FCC adopted rules it believes will minimize future confusion relating to nationwide tests, and established a timeline for implementing the new rules. The FCC believes that the changes can be implemented through software updates to existing EAS equipment.

The most significant change is the adoption of a nationwide location code. EAS alerts include a header code, which includes information on the type and location of an emergency. When the 2011 nationwide test was conducted, the notification included the location code for Washington, D.C. That made sense, as the message was originating from the president. On the other hand, in areas outside the Beltway, some EAS equipment rejected the emergency notification since the emergency was deemed to be occurring outside of the participant�s location.

In light of this electronic NIMBYism, the FCC created a new location code for nationwide alerts: 000000. Based on submitted comments, the FCC determined that the adoption of the �six zeroes� will be a relatively inexpensive solution, with the National Cable & Telecommunications Association estimating that the nationwide code could be implemented by the entire cable industry for $1.1 million. The FCC estimated similar costs for broadcasters.

While the necessary changes to the EAS equipment are relatively simple and can be implemented through software or firmware updates, parties sought to delay the implementation deadline for the new requirement for a period of 12 months. For example, AT&T argued that it will need to engage in substantial testing of the equipment to ensure that it does not fail during future nationwide tests. As such, the FCC doubled its original six-month implementation period and will require EAS participants to come into compliance within 12 months after the new rules become effective.

The FCC�s other significant action involves the development of a reporting system for nationwide EAS tests. The EAS Test Reporting System incorporates the temporary reporting system used during the November 2011 test, along with the updated filing information required under the new rules. In particular, ETRS will pull information regarding the reporting party from other databases where possible.

The new system will also permit batch filing, so that larger EAS participants can submit one report that would cover multiple facilities. Finally, while not tremendously innovative, the new system will permit the participants to review their filings before submission and to receive confirmation of their submissions.

The initial reporting requirements will not go into effect until six months after the effective date of the new rules, or the launch of the new system, whichever is later. Subsequently, EAS participants must submit their �day of test� reports within 24 hours after any nationwide test, and the remaining portion of their report within 45 days after the test.

Update: In my December 2014 article, I noted that a Nashville radio station accidently triggered a cascading false EAS notification on AT&T�s U-Verse systems. The alert was caused by the airing of the November 2011 nationwide alert, which was picked up by other EAS participants. In May, the FCC reached a settlement with iHeartMedia whereby iHeart is required to pay $1 million for the violation. Overall, the FCC has imposed forfeitures of more than $2.5 million in the past year for improper use of EAS tones.

Petro is of counsel at Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP. Email: [email protected].