In the 1930s, the price of wheat went up as markets, and the means to get products to consumers, improved. Farmers� reaction was to plant more. As the supply exceeded demand and the price of wheat dropped, they learned the answer was not always �plant more.�

The sun doesn�t have to set on radio, but broadcasters need to adapt to changing consumer demand.

iStockphoto/mycola It is tempting to see an increase in production as the answer to both high and low demand; it takes a lot of courage to moderate that cycle. Unfortunately, that courage and vision often comes only after a dustbowl.

Conversations and movements about rejuvenating broadcasting usually center on making it look and sound better and creating more of it.

In order to assess where our business and technology are in their life cycle, we should ask these questions: �If there were no radio today, would we invent it? If so, would it look like it does now?�

In the 1930s, the country was in the grip of its worst economic depression and a massive ecological disaster, but radio was proliferating.

If you lived on a dustbowl-era farm, when the sun set, you could search for WLS� Barn Dance, WSM�s Grand Old Opry, WOR�s world reports and big bands. For the price of 200-feet of wire, a very expensive radio and even more expensive batteries, a wind (or some other) charger, you could hear the world. If you were lucky, there might be enough of a ground-wave signal from a Kansas City, Omaha or Denver to get daytime service.

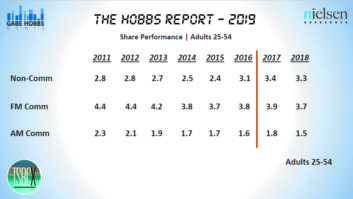

The solution to fill these service gaps, of course, was to create more stations. Today, the same rural farms would find about a hundred over-the-air stations to choose from. There are so many services that most have a fraction of a percent of their listeners tuned-in at any time. Even the most popular stations seldom see double-digit ratings.

With a good AM radio and 200-feet of wire antenna, it�s often easy to count 20 stations running the same talk show. With the exception of some places in the desert Southwest, there are 40 to 70 clean signals on a typical FM car radio. Usually, there is a choice of about a half dozen of any popular genre. Add HD secondary services and we have at least half again as many services. Add satellite and we double or triple the number of services. Throw in an Internet streaming option and there is no real limit on how many services are available.

This growth in services and the dilution of audiences was pretty steady until satellite, cable and digital technologies rather recently catapulted broadcasting into exponential service growth. The Internet is beginning to move us into hyper-exponential service growth.

In a growth industry, it is prudent to produce more to take advantage of demand. Then, as the demand is satisfied and the value drops, the industry must moderate and produce more variety.

The radio industry is probably experiencing its dust bowl. This is not the end of the world or the industry, but the business may be reaching or (has reached) maturity. It may be that for free-over-the-air broadcasting to be healthy and sustainable, there should be a lot less of it on the air.

Nonetheless, there is a great argument that a high-power, low-cost to the consumer broadcast service would be worth some allocation of spectrum to serve everyone in time of emergencies and those who, for whatever reason, elect not to receive content via the Internet, satellite or cable.

We all know that there will be change, but we often don�t foresee just how quickly it can come, or how absolutely disruptive it can be. Or how counterintuitive the inevitable outcome can be.