It’s no secret that the percentage of young people who listen to radio has been on the decline for a decade or more. And while surveys repeatedly show that teens listen to music for at least two hours a day, they no longer tend to listen on terrestrial radio unless they’re in the car with their parents.

So in a world ruled by YouTube, iTunes and Spotify, can teens learn to believe that radio is kind of cool after all?

That was the challenge Jim Timm, president and executive director of the Omaha-based Nebraska Broadcasters Association, decided to take on. He and members of NBA’s board of directors wanted to nurture the next generation of broadcasters. But how?

Timm recalled that the association had conducted a media camp for high school students and that radio was one of the options. He remembered that the students resisted — “Radio’s lame; nobody cares about it,” one said — but that once they started broadcasting, they had so much fun that it changed their perception.

Timm believed this experience could be replicated. He envisioned a project in which high schools could offer students the opportunity to learn how to broadcast via online streaming.

The idea was to partner with local schools to create stations on which students would choose and announce the songs, record news and sports features, and be heard by a potential audience all over the country. The stations would use automation but could go live in certain circumstances. The state association would lend the gear and software to a school; after students’ time with the project ended, the school would ship the gear to the next participating school.

In 2021 Timm ran the idea past Jordan Walton, executive director of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Association, whom he’d met through the National Alliance of State Broadcasters Associations. “I’ve known him for nine years,” Timm says, “and I respect his opinion.”

Walton liked the idea and wanted to collaborate. “So many students today are not even aware of broadcasting,” Walton says. “We want them to see how much fun doing radio can be. Maybe a few of them will [decide] to be involved with media, where they weren’t before.”

Thus the initiative became a joint project of two state associations. Timm and Walton began meeting weekly via Zoom. Their work developed into the High School Radio Project.

They chose the online platform (Live365), music scheduling software (MusicMaster) and automation software (PlayoutOne); and they purchased audio broadcast equipment from BSW, including a Rodecaster Pro audio mixer, two microphones and all necessary cables. They decided they would offer schools a choice of music libraries: alternative rock, country, class rock and top-40. They also provide Benztown Branding to create promotional content and a guide to assist the teacher.

Each association funded its respective radio project, with hard costs in the first year running about $10,000 in each state. Annual costs to operate each station is another $5,000 or so.

The schools don’t pay anything to participate. The school must provide an internet connection; a PC that can connect to the mixer via USB; audio editing software like free Audacity; and classroom time.

The streams are heard on Live365, the HSRP website and Alexa skills.

Good fit

To pilot the project in Nebraska, Timm thought of a high school teacher named Mark Hilburn, who taught at Millard West High School in Omaha. He is an award-winning journalism teacher and the former president of the Nebraska High School Press Association. Given Hilburn’s love of media, Timm believed he would be a good fit.

“He started out with seven students, five boys and two girls,” Timm recalls, “and worked [radio broadcasting] into the curriculum. He taught how to use the software and even how to do news.” The station debuted in January with the name “The Uproar.”

Hilburn says he had no problem getting students interested. “I told them they could be the first in the state to do a high school radio station.” And once they learned the equipment, which they found user-friendly, they couldn’t wait to participate. “They loved being hands-on, creating the broadcasts.”

The more programs they put together, the more enthusiastic they were. “The students liked hearing their voices on the station. And some of the [other] teachers began playing the station in their classroom,” Hillburn said.

Students chose and announced the songs and created reports about school news. And while software gave students the flexibility to record breaks in advance, students also wanted an opportunity to broadcast live.

In May they went on the air live for an hour, and it was well-received at the school. “We’d like to do some more live programs, including sports,” he said.

Hilburn benefited from Timm’s guidance and feedback. Also valuable was support from long-time Omaha program director and announcer Kurt Owens. He collaborated with Timm and Walton to “create a series of video tutorials, as part of the training provided to students and teachers,” Timm said. Those are available under a training dropdown here.

The videos are short, designed to help students to learn the basics of such things as recording and loading the audio or building a clock in MusicMaster. Once the station was up and running, Timm made sure Hilburn and his students got frequent support.

“Kurt visited the Millard West classroom with me on a few occasions, providing veteran coaching and instruction to the students in real time.”

Owens enjoyed his experience working with high schoolers. “I had a chance to work on voice tracking with each of [the students], and it was great to see them excited about the idea of radio, and that someone might be listening to them … Of course as with most things there were a few who took to the radio project right away and turned into great leaders. But by the time we did the live show, the whole class was excited and all participated.”

Hands-on learning

In Massachusetts, the program ran last year at Watertown High School near Boston, guided by media teacher Todd Robbins, a veteran local sports broadcaster who had helped build up the number of media courses offered at the school.

Robbins spoke with Radio World this summer about the experience.

In the beginning, he had about 12 students participating in the online station. “I was very impressed with what Jim and Jordan put together. The software was similar to what you’d find at a [typical] radio station.”

Three seniors were especially interested. “They did the voice-tracking. They ran the programs.” Gradually, more students got involved, and all received hands-on training.

His “Radio and TV News” course dovetailed into the project. “I let the students [in that class] produce the newscasts.” And because the students were choosing the songs, doing the announcing and producing the content, Robbins said they seemed invested.

“My students wanted to listen to it. And the interest increased as we promoted it. It was a 100% success.” Robbins said the project teaches students about decision-making, how to handle mistakes and how to learn by doing. “If students can take with them what they learned from the High School Radio Project, these are marketable skills.”

The program has concluded at Watertown High, and Robbins has moved on to another job. Westfield Technical Academy in Westfield, Mass., is running the radio project this year, and Walton said a station is in the works at Thurston High School in Redford, Mich., through the Michigan Association of Broadcasters.

Walton believes the project promotes the value of audio storytelling, as well as introducing students to the possibility of careers in broadcasting. The project “gets kids to see how much fun doing radio can be.” He hopes the project will continue to spread to other schools. “For me, the takeaway is that students can still get excited about broadcasting if given the opportunity.

Michigan Campaign Targets Youth

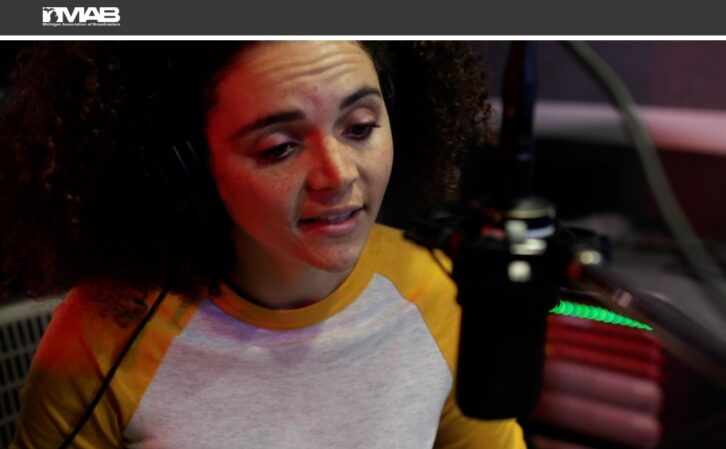

The Michigan Association of Broadcasters recently launched an innovative industry recruitment campaign called “Be There.” It is designed to provide young people a look at broadcast careers and an understanding of the ecosystem of a station, whether on-air or behind the scenes.

The marketing effort includes television and radio spots, social media, printed materials and a long-form video. These resources, along with a new website, showcase career opportunities available at TV and radio stations in the state.

MAB said that the long-form video is intended to be shown at high schools and colleges. There are detailed descriptions of more than a dozen media careers including reporters, anchors, meteorologists, hosts, engineers, I.T. professionals, sales, music directors, editors and traffic managers.

The accompanying image is from the website BeThereMichigan.com.